The 1807 Yorkshire election was the most expensive prior to the 1832 Reform Act [25-minute read]

Context

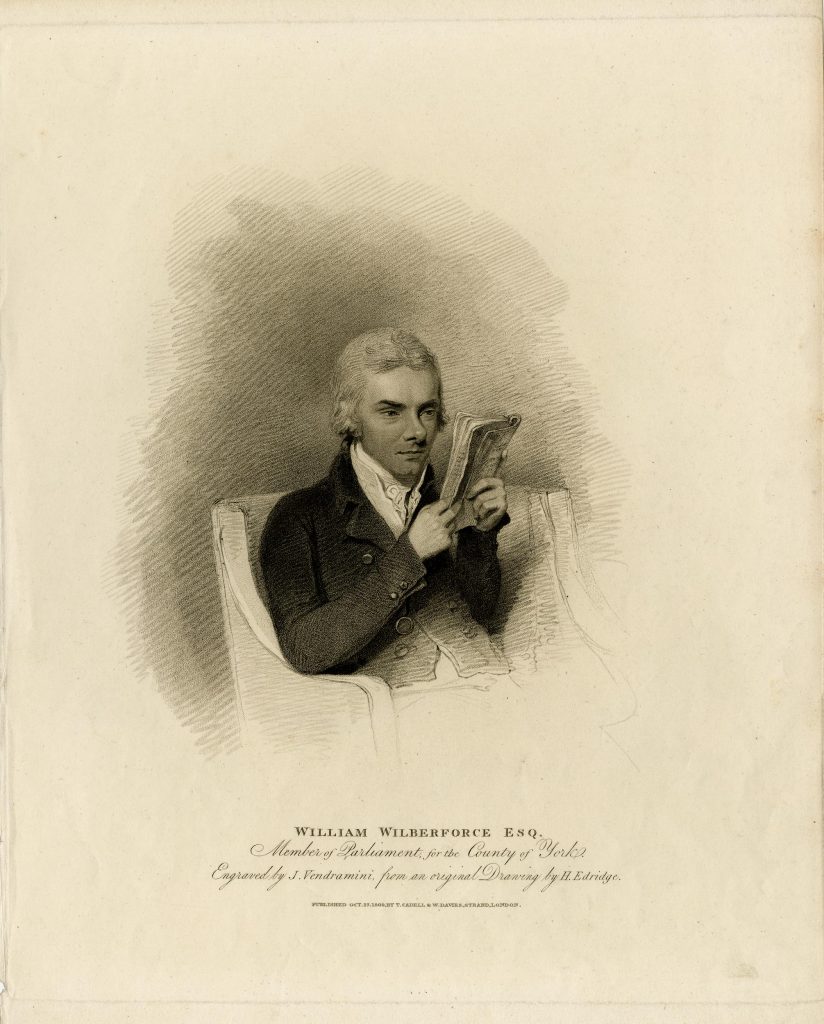

The colossal county of Yorkshire constituted the largest constituency in England by some distance, divided into East, West, and North ridings. The West Riding alone had a population of almost a million people by 1831 (71 per cent of Yorkshire’s population, though the West Riding provided only half the county’s voters). Many were clustered in industrial towns, such as Leeds, Halifax, and Sheffield, which had grown over the course of the eighteenth century but had never been granted the status of parliamentary boroughs. Other parts of the constituency remained much more rural. On account of its size and variety, the leading politician, Charles James Fox, gave it as his view that, ‘Yorkshire and Middlesex between them make all England’.[1] Meanwhile, William Pitt the Younger called William Wilberforce, an MP for Yorkshire, ‘the whole people of England’, because he represented its most populous county.

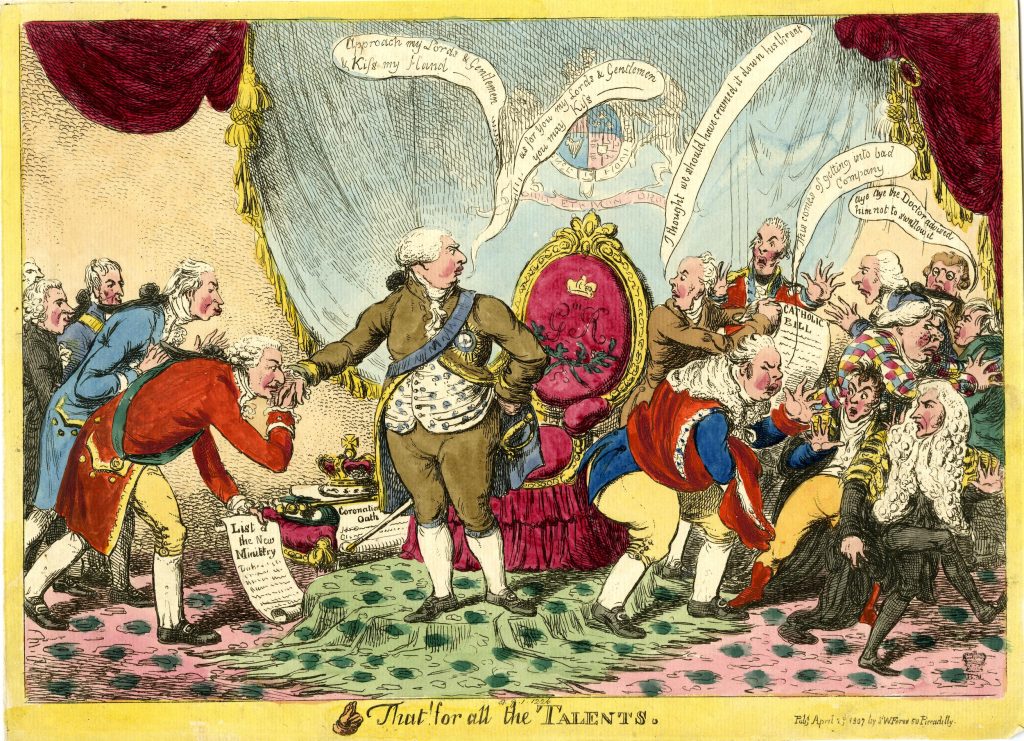

In 1807, a general election was triggered by George III’s dismissal of the ‘Ministry of All the Talents’. Among the divisive issues of the day were the trade in enslaved people, with a controversial Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade having been passed by the outgoing Government in March 1807, and the civil rights of Roman Catholics. At this period, Catholics were unable to vote or hold public office. The outgoing Government had attempted to pass a Catholic Bill, which would have allowed Catholics to serve in the British army up to the rank of general, but it had been defeated, in part due to the opposition of the king.

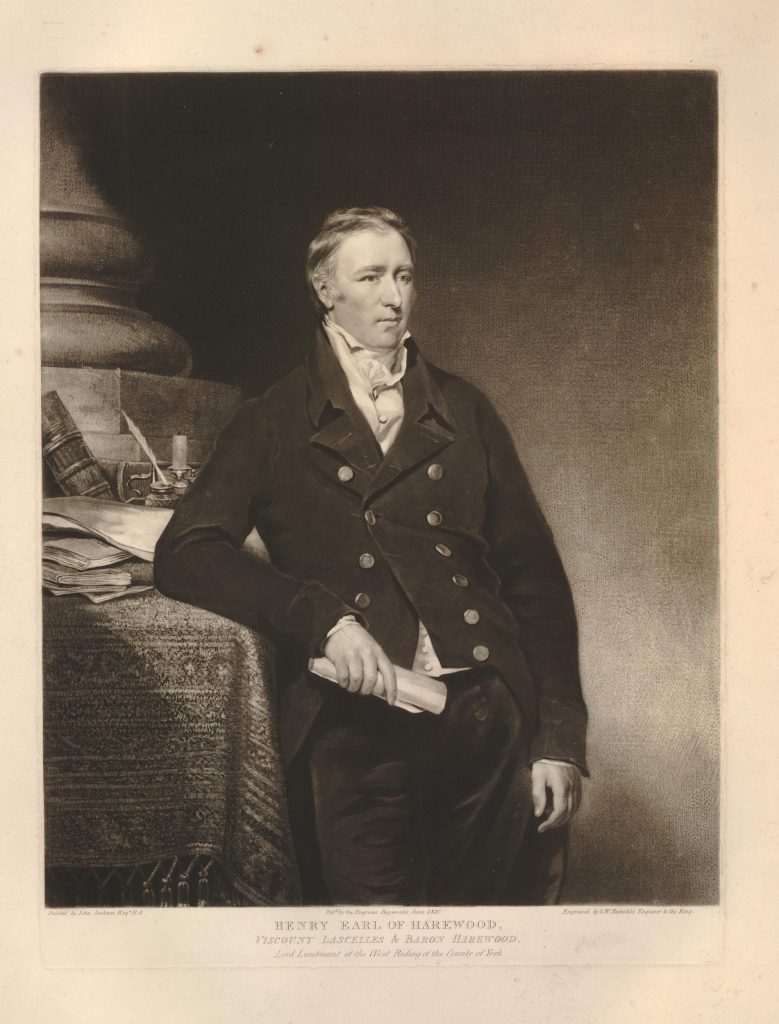

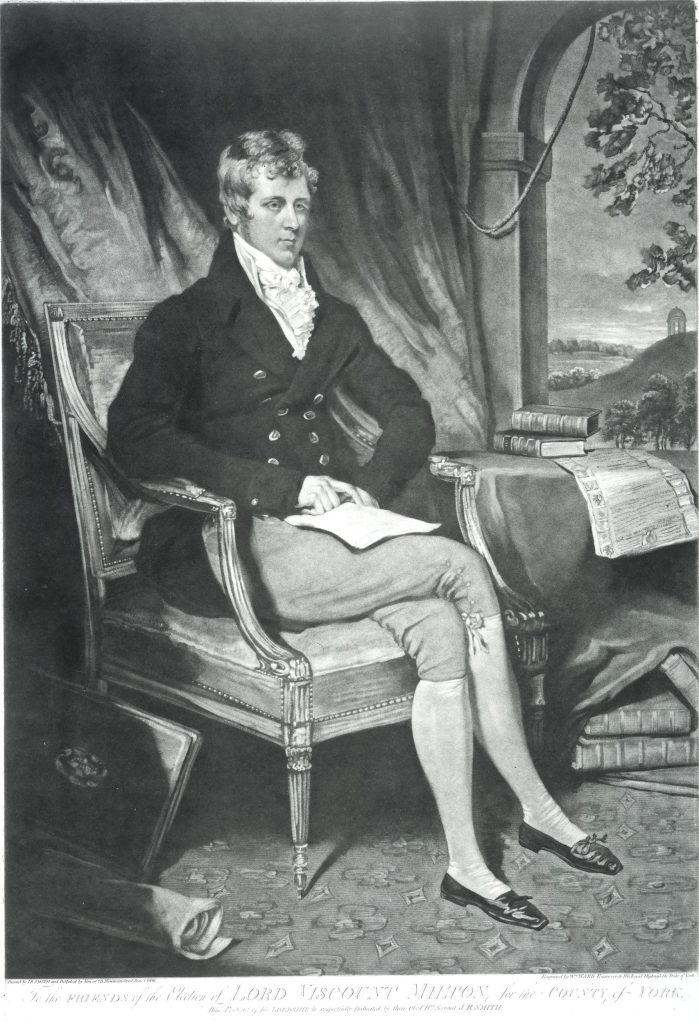

The 1807 election was the first to be contested for the Yorkshire constituency since 1741. Such an enormous constituency was extremely expensive to fight, requiring huge resources to mount a campaign and huge wealth to influence the electors. The candidates in 1807 were William Wilberforce of Hull (a Tory); the Honourable Henry Lascelles of Harewood House (also a Tory); and Charles William Wentworth Fitzwilliam, Viscount Milton of Wentworth Woodhouse and Milton Hall (a Whig).

Wilberforce, the famous abolitionist, was a longstanding representative of Yorkshire in Parliament, having served as ‘Knight of the Shire’ (MP) since 1784. He was seen as a lively and charming figure. His campaign colour was pink.

Lascelles had also served as MP for Yorkshire from 1796. Recognising that his attitude to the regulation of the wool trade made him unpopular with his constituents and that he would be defeated in an election, he had withdrawn from a potential contest in 1806. He was the second son of Lord Harewood, a leading Yorkshire peer, and was seen as the ministerial candidate. His campaign colour was blue.

Lascelles’ place as MP for Yorkshire had been taken in 1806 by William Fawkes. His retirement provided the opportunity for a third candidature in 1807: the Whig, Lord Milton. Viscount Milton was the son of Earl Fitzwilliam of Wentworth Woodhouse. Fitzwilliam had inherited the very substantial political interest, along with the extensive estates and collieries of his uncle, the 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, in 1782. Like Wilberforce, Milton had an Evangelical outlook. His campaign was largely supported by members of the influential cloth trade in the West Riding. His campaign colour was orange, a colour associated with Protestantism and the 1688 Glorious Revolution.

Campaign Issues

The key election issues in 1807 were the abolition of the slave trade, Catholic emancipation, the Yorkshire wool industry, and electoral independence. Abolition of the trade in enslaved peoples was supported by Yorkshire’s Methodist community and led by Wilberforce. Lord Milton similarly espoused the cause of abolition during his campaign. However, Lascelles was no supporter of abolition given his family’s interests in the West Indies. The Lascelles owned six plantations, with 1,277 enslaved men and women, in Jamaica and Barbados. As for the Catholic question, Milton, as a Whig was aligned with the Foxite agenda of emancipation. Wilberforce and Lascelles, the Tory candidates, opposed Catholic emancipation. Indeed, Lascelles’ banners were often inscribed with the slogan ‘No Popery’.

The start of the election

Lord Milton was only twenty years old when the writ was issued for the Yorkshire election on 30 April 1807. The writ was supposed to arrive in York the following day, but was intercepted by one of Lord Milton’s election agents, and delivered to York only on 4 May, which was Lord Milton’s twenty-first birthday. The delay ensured that he was old enough to sit in Parliament.[2] Upon receipt of the writ, the office of Richard Wilson, the sheriff, declared the date of the election to be 20 May.

Milton’s youth proved a gift to his opponents’ hack writers. Wilberforce was 47 when he entered the campaign , and Henry Lascelles was 39. Throughout the campaign, Milton was referred to as the ‘grown baby’. The song below, ‘Lascelles and the Baby; or the Glorious Fifth of June, 1807’, was published in the squib book, Yorkshire Election. A Collection of the Speeches, Addresses and Squibs, produced by all the parties during the late contested election for the County of York (pp. 98-99). The ‘Glorious Fifth of June’ refers to the date the polls closed during this contest, but played on the name of the naval battle between British and French fleets and a commemorative play by Sheridan from 1794, known as the Fourth Battle of Ushant or the Glorious First of June. The lyrics were sung to the tune ‘Abraham Newland’.

MuseScore and Audacity (2023).

Our Joe’s come from York,

Where, he says, they’d strange Work;

(Efeaks, there’s not telling what may be!)

For that Mr. Lascelles

And A Legion of Yells

Did furiously fight with – a Baby,

They call’d him a pitiful Baby,

A white-looking, red-headed Baby!

But he laugh’d at their Rattle,

Then offer’d them Battle,

And manfully fought, though – a Baby!

When the Combat began,

Many Lookers-on ran

To see Lascelles fight with the Baby:

But, strange! ‘mongst these Bands

Who held up their Hands,

Few held up their hands for the Baby!

For Falsehood and Fraud fear’d the Baby;

Disloyalty grinn’d at the Baby;

While his numerous Friends

Gain’d their laudable Ends,

And insur’d the Success of the Baby!

For full fifteen Days

(Our Joe further says,)

The Giant was fought by the Baby!

When the Snake in the Grass

And each big-looking Ass

Join’d their Notes – ‘gainst the conquering Baby.

The Low-Great and the Knowing, half crazy,

Vow’d – that they never more should be asy!

And did haughtily gabble,

‘Bout the insolent Rabble,

Who had triumph’d, in choosing… the Baby!

Now (like travelling Quacks,

With Humbugs on their Backs,)

They rail as they stroll, at the Baby;

And stale are their Jokes,

‘Bout MILTON and FAWKES,

Since they found Manhood’s Pow’rs in the Baby.

Britain’s Foes know that strong is the Baby;

The Yorkshireman’s Friend is the Baby!

FITZWILLIAM, rejoice

In the Man of our Choice!

England’s Champion behold, in – her Baby!

The build up to the poll: 4–19 May 1807

Between the proclamation of the writ and the nomination of candidates (4–13 May), Wilberforce travelled around Yorkshire to canvas and pay his ‘personal respects to the freeholders’, notably in the manufacturing communities in the West Riding, including Leeds, Wakefield, Bradford, Halifax, Huddersfield, Sheffield, and Rotherham.[3] He had particularly strong support from West Riding merchants and landlords.[4] Lady Bessborough recounted that Wilberforce led in the poll ‘from mere weight of character in such an election as this, when money is supposed to do all.’ Lascelles, however, had been promised over 11,000 votes in advance of the poll, making the race a close contest indeed. Meanwhile, on 5 May, Lord Milton addressed voters at the White Cloth Hall in Leeds.[5] He promised to pay for his supporters’ meals, accommodation, and horses if they travelled to York to cast their votes for him.[6] He presented himself as a friend to their interests:

Gentlemen, I can assure you with great truth that I am not actuated by any animosity to either of the other Candidates. I stand upon my own grounds, and upon them I will stand or fall. I offer myself to you as a perfectly independent Man … I shall above all, Gentlemen, pay the greatest attention to your trade [wool]; I will attempt to make myself master of it in all its branches — I will observe the strictest justice, and most perfect impartiality between the merchant and the manufacturer. I am deeply interested in the prosperity of your trade, because upon it depends the prosperity of the British Empire. You, Gentlemen, are the most industrious, the most useful of his Majesty’s subjects.[7]

Wilberforce and Lascelles also addressed voters at the White Cloth Hall in Leeds.[8] The Hull Packet reported that Wilberforce was ‘accompanied by a considerable number of merchants, and was very favourably received’. He gave a speech from the hustings in the hall, saying, ‘he was more than repaid by the marks of attention which he every where experienced, and which was as honourable to the people of Yorkshire as to himself, because it was a proof that they would support a man without any other claim or patronage than what resulted from an earnest endeavour to discharge his duty to his constituents and his country’.[9] Wilberforce’s agents were active in getting his supporters to the polls, appointing election agents at the Tiger Inn and Beverley Arms to arrange for voters’ transportation to York.

On 13 May, the nomination meeting took place in York’s Castle Yard at 11am. An initial show of hands favoured Wilberforce and Lascelles. Polls opened a week later on 20 May, but tensions were already running high in parts of the county. On 19 May, according to the British Press,

A dreadful riot occurred at Leeds … originating, it is said, in a quarrel between two boys of the opposite parties of Lord Milton and Lascelles. The accounts are so various and confused, that it is difficult to learn the exact result. The military were called in, and two men, it is said, were killed, and upwards of 100 wounded. Such is the report.[10]

The Hull Packet reported that Lord Milton’s supporters met at the Leeds White Cloth Hall to proceed in their carriages to York. Some of Lascelles’ supporters were found among the crowd with a paper supporting their candidate, and Milton’s supporters began ‘hooting and hustling them’. The mayor ordered the Riot Act to be read, with ‘troops … ordered to scour the streets, with drawn swords, galloping down foot paths, entering even private dwellings, and pursuing the inoffensive multitude…’[11]

Polling: 20 May-5 June 1807

From 20 May to 5 June, the polling took place at Castle Yard in York — fifteen tense days punctuated by mobs and sideshows. On 20 May, the polls opened at 10am. The sheriff made a speech, followed by the entry of the three candidates, who presented themselves on horseback, as knights with swords. They were then proposed and seconded. According to Jonathan Gray, alderman of York, solicitor and under-sheriff superintending the poll, ‘Lord Milton’s friends had dextrously marshalled his forces immediately in front of the hustings, by which means his numbers were best displayed…’. A show of hands was requested, which this time favoured Lascelles and Milton, prompting Wilberforce to demand a poll.[12] Each day thereafter, the castle gates were opened at 8am. in advance of the opening of the poll at 9am. They closed at 5pm., except on the final day when voting ended at 3pm. Every evening, after the day’s returns were made and recorded, the Sheriff announced the State of the Poll from the hustings to show that day’s polling and the cumulative result. The State of the Poll was followed by speeches from the candidates in order of the results of that day’s poll.[13]

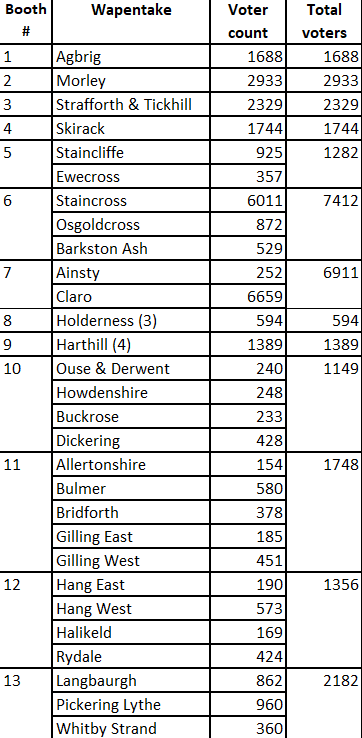

The hustings had been erected at the candidates’ expense in front of the Court of Justice in York, facing Castle Yard. There was one poll booth for disputed votes, and thirteen poll booths for voters from different wapentakes, each labelled accordingly.[14] Wapentakes originated from Danelaw, and were similar to the administration of hundreds in the south of England, the name deriving from the Old Norse vápnatak, an ancient practice of casting a vote by touching one’s weapon. According to the sheriff, many of Lord Milton’s supporters came from the three most densely populated wapentakes (Strafforth and Tickhill, Agbrig, and Morley), which created a problem for him:

This circumstance operated in the first instance to his Lordship’s disadvantage; for whilst his opponents had the advantage of eight or nine booths as recipients for their votes, and were therefore able to pour in supplies and feed the poll as fast as it could receive them, as well as to send home the polled voters immediately, the booths for the three districts chiefly in Lord Milton’s interest were crammed beyond the faculties of their digestion; hence Lord Milton was kept low on the poll, and had always in York the greatest number of unpolled voters.[15]

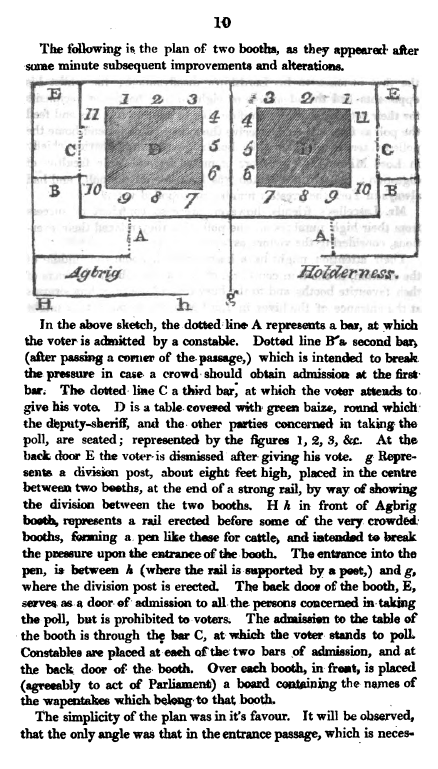

Much thought went into the design of the polling booths, as explained in this detailed description of their layout. Voters were ‘processed’ through the booth in tallies, entering at one side and exiting at the back. Efficient passage through the booth was seen as crucial, as was crowd management and the importance of avoiding any build up of men wanting to vote. Each of the 13 poll booths was manned by one deputy sheriff to examine every voter and refer any objections to voters to the sheriff’s booth, plus: one poll clerk to record the vote; three election agents (one for each candidate) to object to doubtful votes; three messengers (one for each candidate) to conduct the objected voters into court; and three cheque clerks (one for each candidate).

Upon entry to the poll booth, the voter was asked:

- Whether they were a freeholder

- Their name

- Place of abode

- Occupation

- Where their freehold lay, and in whose occupation (i.e., landlord, tenant).

An enquiry about any possible objections to their entitlement to vote was then made, before the voter was asked for their choices.

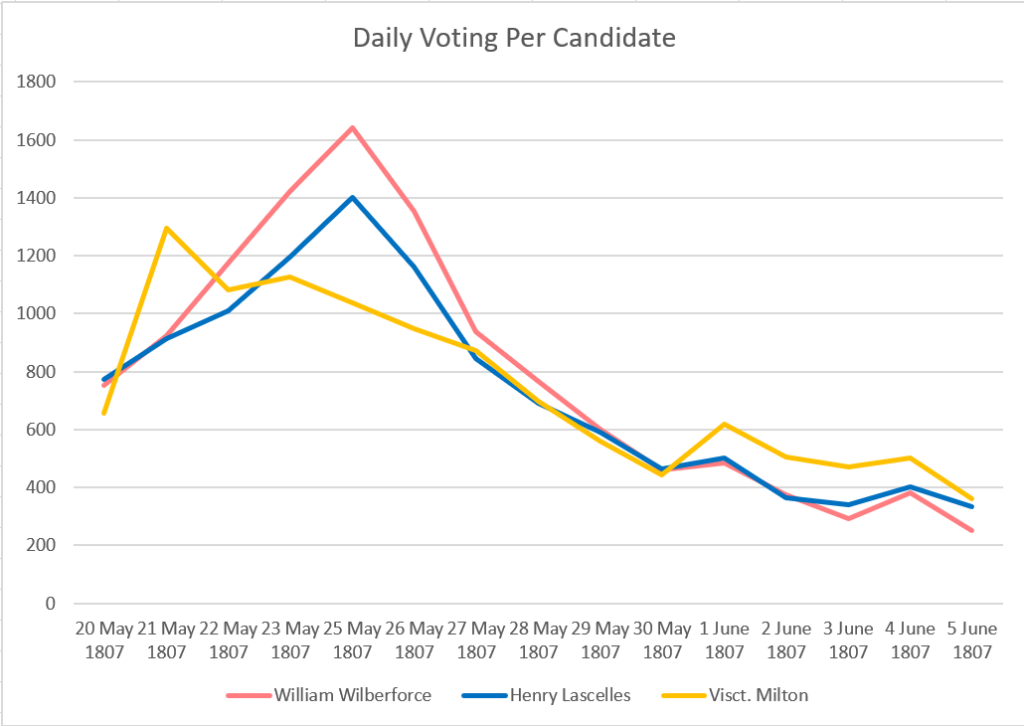

Voting was brisk, with 2,181 voters casting their polls on day one, rising to a peak of 4,080 on the fifth day, before a decline in numbers set in. The graph below shows an early surge in popularity for Lord Milton at the start of polling, though he was quickly overtaken by Wilberforce. In the final week of voting, Lord Milton’s campaign was able to mobilise marginally more support than either of the other two candidates.

The close of the polls: 5 June 1807

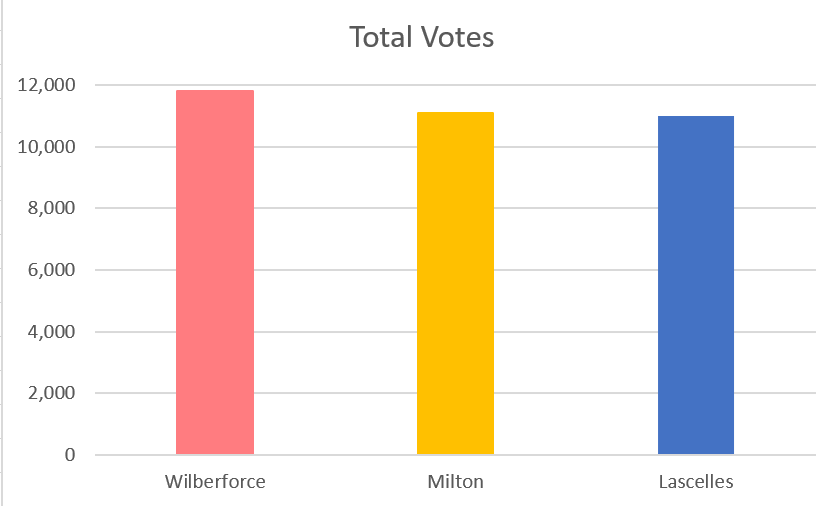

On 5 June, the polls closed at 3pm with the firing of a cannon. At this point, hundreds of voters were still unpolled, but 23,007 had been able to cast their votes. The election returned Wilberforce and Milton as Knights of the Shire for Yorkshire. The High Sheriff announced the result, after which the Indenture of Election was read by the county clerk.

Wilberforce (11,808 votes) and Milton (11,177 votes) were returned as MPs, though Lascelles (10,990 votes) challenged the result. Lady Holland wrote:

A petition against Milton was ready, and upon the point of being presented, but he judiciously procured one also against Wilberforce, which, being held in terrorem, inclined Wilberforce to exert and pledge himself on behalf of ministers who came forward and promised to drop the petition against Lord Milton, if he in return would stipulate that the one against Wilberforce should be dropped.

Voting in the election had been unprecedentedly frenetic, according to the Yorkshire Herald:

Nothing since the days of the revolution [in 1688] has ever presented to the world such a scene as has been for fifteen days and nights passing within this great county. Repose or rest have been unknown in it, except it was seen in a messenger, totally worn out, asleep upon his post-horse, or on his carriage. Every day the roads in every direction, to and from every remote corner of the county have been covered with vehicles loaded with voters; and barouches, curricles, gigs, flying wagons, military cars with eight horses to them, crowded sometimes with forty voters, have been scouring the country, leaving not the smallest chance for the quiet traveller to urge his humble journey, or find a chair at an inn to sit down upon.[16]

Electoral Culture

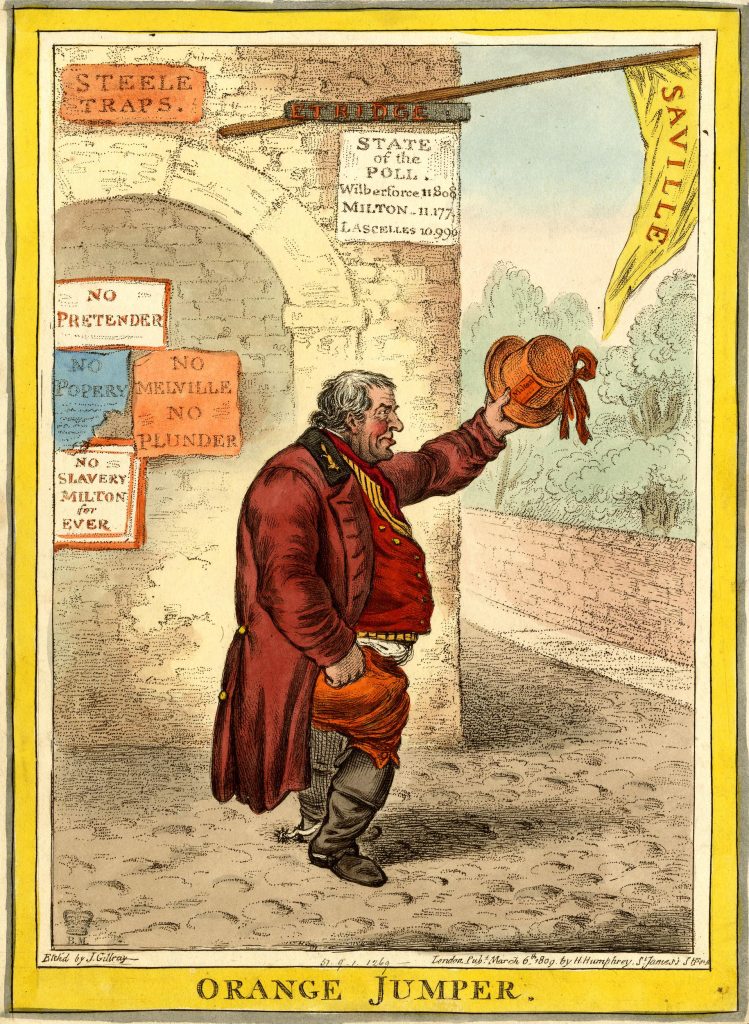

Relatively little visual or material culture from the 1807 election has survived to the present day. One exception is a caricature by James Gillray entitled ‘Orange Jumper’, depicting a conspicuous orange-clad supporter of Lord Milton. A letter to Gillray in 1809 noted that, ‘Orange Jumper is as well known in Yorkshire as the King of England … [he] has been a celebrated Horse Breaker 40 years’. He boasts, ‘That he has had every bone in his skin broken & that he has been in every jail in England’.[17] According to one source, ‘“Orange Jumper” was employed to carry dispatches regularly backwards and forwards from York to Lord Milton’s father at Wentworth Woodhouse near Rotherham, a journey of over forty miles.[18]

Following the final poll, Wilberforce and Milton, as the victorious candidates, issued medals to commemorate their victories. Wilberforce’s pewter medal is edged with oak leaves and acorns, symbols of strength and wisdom. It celebrates Wilberforce’s past accomplishments, including the abolition of the trade in enslaved peoples and the independence of Yorkshire’s population.

Milton’s celebratory medal was produced in silver, a more costly material than Wilberforce’s pewter. The back is inscribed with ‘Milton For Ever and 11,177’ to record the number of votes supporting his campaign.

A medal for Lascelles has also survived from this election. Since his campaign was not successful, it is unclear whether this was a campaign token handed out to supporters during the election, or a medal to thank them post-election. Like the medals of Wilberforce and Milton, Lascelles’ medal also proclaims the independence of his campaign.

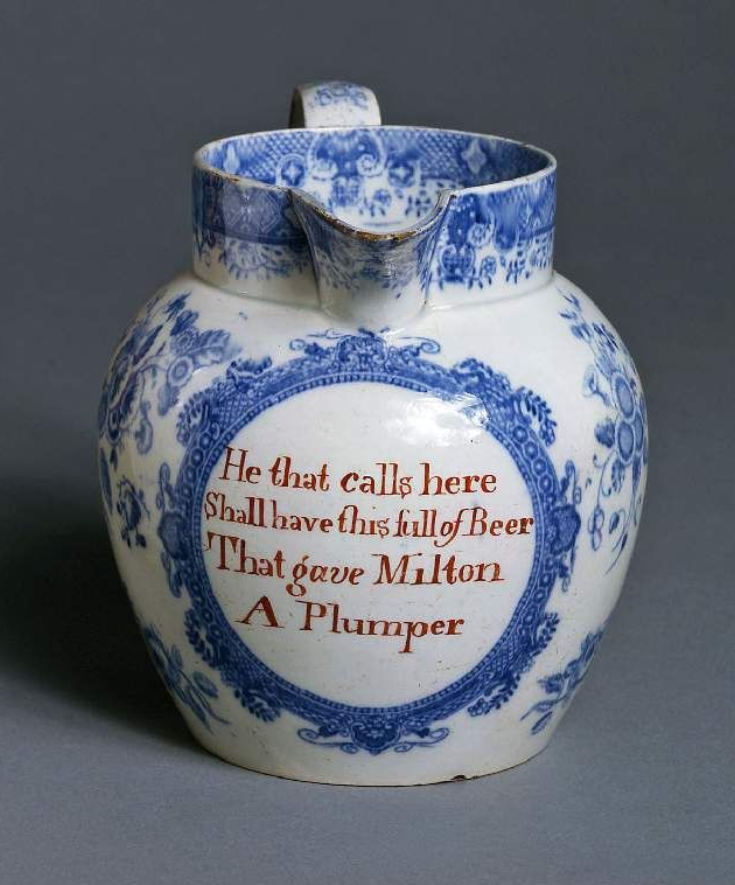

Lord Milton’s campaign strategy was to encourage voters to plump for him, using only one of their votes to support his Whig candidacy, rather than helping either of the Tory candidates. He also planted the notion of a coalition between Lascelles and Wilberforce in the press and the minds of voters, despite Wilberforce running an independent campaign and spending a fraction of the money laid out by Milton and Lascelles. Indeed, a transfer-printed jug in the Fitzwilliam Museum preserves Milton’s campaign tactic in material form, as it is inscribed with the message, ‘He that calls here / Shall have this full of Beer / That gave Milton / A Plumper’.

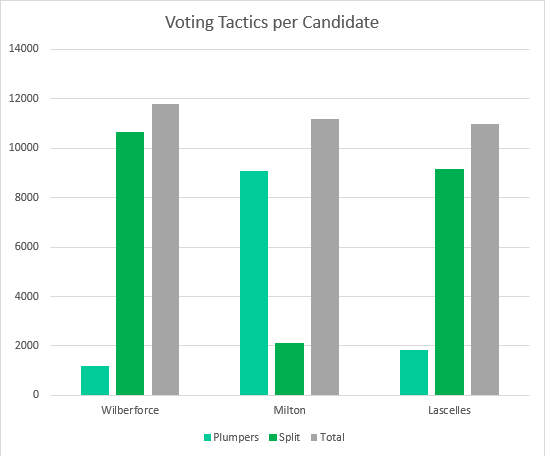

Voting Tactics

Since most constituencies were represented by two MPs, each voter had two votes which they could use in a variety of ways. They could cast both votes for complementary candidates (voting ‘straight’); divide them between two rivals (‘split’); or cast only one of their votes and discard the other (in what was known as ‘plumping’), in order to give that candidate an advantage over the others. Lord Milton’s campaign for plumpers was hugely successful, with 9,061 plumps of 11,177 total votes (81.06%) to support his candidacy. In comparison, most supporters of Wilberforce and Lascelles split their votes, giving one each to the two Tory candidates, with only 10.05% and 16.7% plumping for these two candidates respectively.

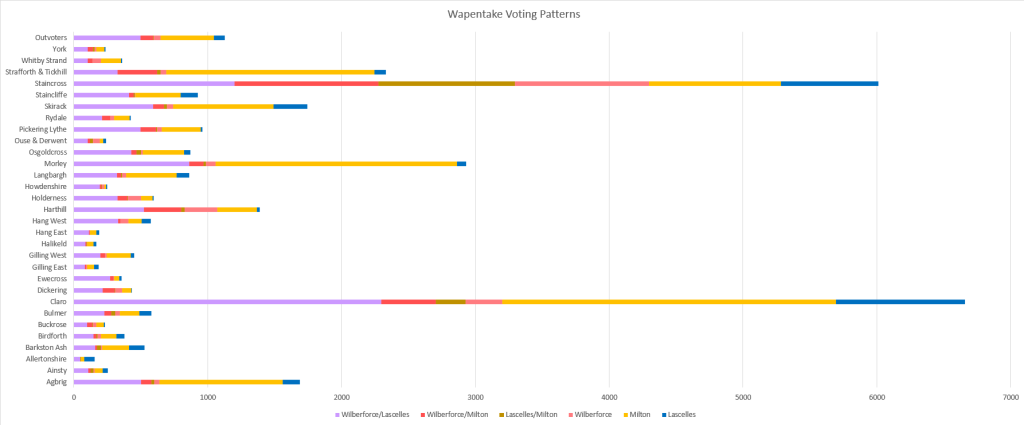

Geographically, Lord Milton received significant support from the wapentakes of Claro, Morley, and Strafforth and Tickhill, all in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Wilberforce, by comparison, received most plumps from Staincross. However, across the majority of wapentakes in Yorkshire, most voters split their votes between Wilberforce and Lascelles.

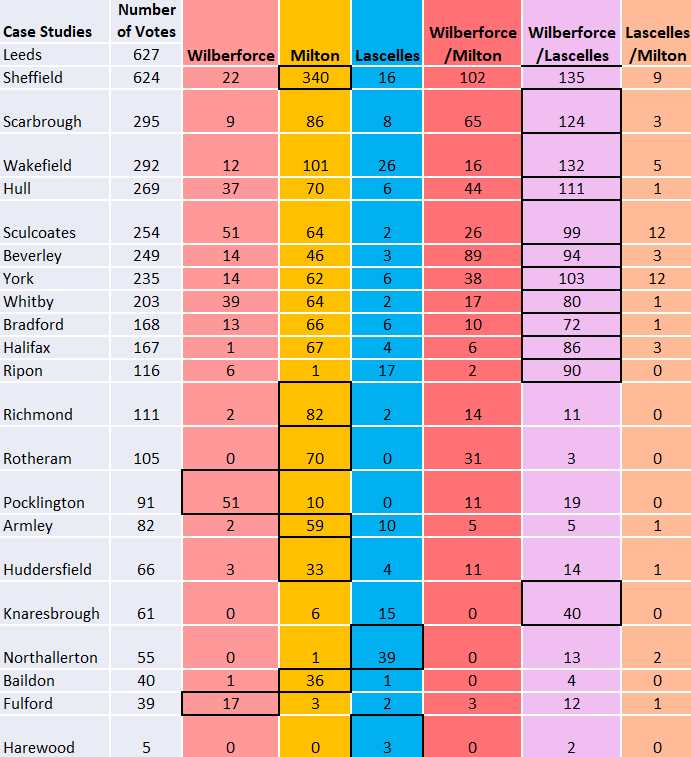

The poll books for this election go into such detail that we can break down the voting tactics to individual wapentakes. The table below shows how the votes were cast in a selection of Yorkshire towns and cities. In Pocklington and Fulford, Wilberforce received the highest number of plumpers, while Lascelles was more successful with plumped votes in Northallerton, a borough where members of the Lascelles family typically sat as MP from 1745 (and would continue to do so through to the Reform Act of 1832). Similarly, Lord Milton was very popular in Rotherham, near which Wentworth Woodhouse was located. As Sheffield was a centre of radicalism, it is also unsurprising to see that 340 people plumped for Milton, the Whig candidate, against the Tories.[19] However, as the majority of Lord Milton’s supporters were plumpers, it is unsurprising to see his name at the top of the poll for so many communities. The number of Milton’s plumpers was in close contention with voters who split their votes between the two Tories, Wilberforce and Lascelles. In Halifax and Wakefield in particular, where election violence broke out among Milton supporters, there was a close contest between plumpers for Milton and splits for Wilberforce-Lascelles.[20]

It is also worth noting that 1,852 voters were turned away from polling, likely to be due to objections surrounding their voting qualifications. Of these, 1,490 had voted for Lord Milton and 300 had voted for Lascelles. 1,126 ‘outvoters’ participated in the election, coming to York from outside the county . The majority (291) were from ‘Hullshire’, comprising parts of the city of Kingston upon Hull and its surrounds in the East Riding of Yorkshire, which had been granted the unusual status of a ‘county corporate’ (meaning it was separate from the larger county of Yorkshire). Others travelled from Lancashire (256), Durham (95), Nottinghamshire (63), Derbyshire (62) and Lincolnshire (61), or in some cases from even further afield.

Following the election, Lord Milton alone was chaired through the streets of York; Wilberforce was not chaired due to the illness that had forced him to stop canvassing on 2 June. The chairing procession started happily:

Lord Milton, after having girt on the knight’s sword, then mounted a very elegant chair, beautifully ornamented with laurel and orange coloured Ribbons, Silks, &c. – The procession proceeded three times round the Castle Yard, and paraded the principal streets of York, amidst the cheers of the populace, and the enlivening smiles of many Ladies, who lined the windows in every street though which his Lordship passed, waving Orange coloured handkerchiefs…

But when the procession passed the George Inn, Lascelles’ headquarters, things took a violent turn:

… some wretch … threw a tile or a brick with excessive violence, which had very near struck Lord Milton’s head, and at the same moment, a vast number of ruffians, “who foolishly imagined that they could honour Mr. Lascelles by disgracing themselves”, rushed out of their lurking places … and attempted to throw his Lordship from the Chair; in this attempt they fortunately did not succeed, but they did succeed in completely dismantling and stripping the chair of its ornaments…[21]

Nevertheless, Lord Milton was able to reach his campaign headquarters at Etridge’s Hotel, where he addressed the crowd. That evening, a victory dinner for 200 gentlemen was held in the Assembly Rooms.[22] It was followed the next day by a gala at Malton to thank Lady Strickland for her support (she was celebrated as a ‘Female Patriot’), and an election ball took place that evening at Milton Hall.[23] Wilberforce’s election committee held a victory dinner for his supporters at York Tavern.[24] So ended one of the most fervid and costly elections of the period.

Expenses

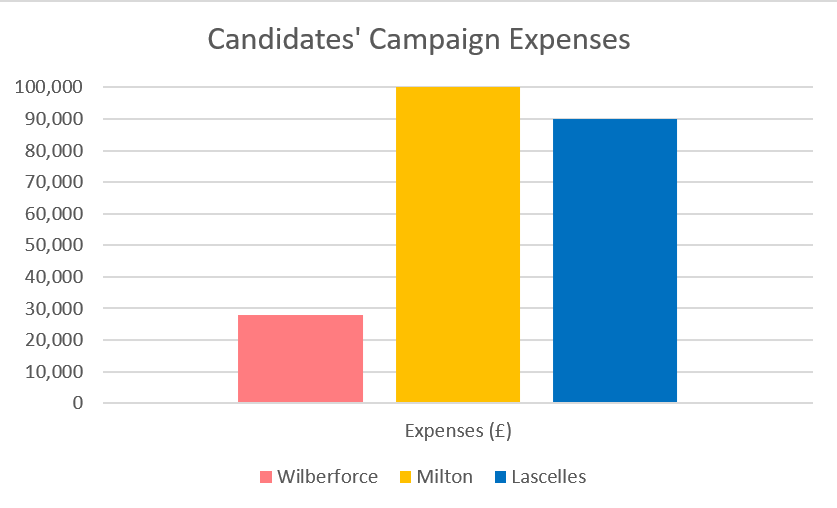

Wilberforce’s campaign for the abolition of the slave trade made him a favourite of Yorkshire’s Methodist community. His election expenses in 1807 came in around £28,000 (most of which came from volunteers’ donations), far below the expenditure incurred by both Milton and Lascelles. Over the course of Lord Milton’s campaign, his father (Lord Fitzwilliam) spent nearly £100,000. The campaign committee paid for transportation, accommodation, and food for Milton’s supporters. During the campaign, Lascelles spent over £90,000, drawing from the revenues from his family estates in Barbados. The 1807 Yorkshire election was the most expensive election prior to the 1832 Reform Act.

[1] Samuel Wilberforce, The Life of William Wilberforce (London, 1872), 150.

[2] Jonathan Gray, An Account of the Manner of Proceeding at the Contested Election for Yorkshire in 1807 (York: Thomas Wilson, 1818), 1.

[3] William Wilberforce, A Letter to the Gentlemen, Clergy, and Freeholders of Yorkshire; occasioned by the late election for that county (London: Luke Hansard, 1807), 4.

[4] Ellen Wilson, Mass Politics in England before the Age of Reform: the Great Yorkshire Election of 1807 (Carnegie Publishing, 2015), 127.

[5] Wilson, 149.

[6] Wilson, 170.

[7] Yorkshire Election. A Collection of the Speeches, Addresses and Squibs, produced by all the parties during the late contested election for the County of York (Leeds: Baines, 1807), 14-16.

[8] Wilson, 129.

[9] Hull Packet (19 May 1807), p. 3.

[10] British Press (23 May 1807), p. 4.

[11] Hull Packet (26 May 1807), p. 4.

[12] Gray, 23-4.

[13] Gray, 28.

[14] Gray, 9-10.

[15] Gray, 9.

[16] Yorkshire Herald (6 June 1807).

[17] British Library, Add MSS 27337, f.112.

[18] The Art Journal (London: Virtue and Co., 1865), iv, 377.

[19] Wilson, 23.

[20] Wilson, 244.

[21] Yorkshire Election, 107-8.

[22] Yorkshire Election, 107-8.

[23] Wilson, 145, 264.

[24] Wilson, 257.