Electors often had their entitlement to vote challenged, so had to prove their case [10-minute read]

The requirement for every elector to justify their right to vote at the hustings was a routine part of Georgian elections. Eighteenth-century England did not enjoy universal enfranchisement, and the confusing array of franchises (which determined who was legally entitled to vote in parliamentary elections) created fertile ground for legal challenge over individual voters’ qualifications. A closer look at the parliamentary borough of Minehead highlights how, before the reforms of the nineteenth century, disputes over voters’ rights could ironically allow non-voters to play a crucial role in parliamentary elections – but that the process could also be manipulated by powerful political figures.

A small coastal town in Somerset, Minehead’s politics were dominated for most of the eighteenth century by the Luttrell family of Dunster Castle. Over the course of the century, a drastic decline in the port’s economic importance was mirrored by the general dilapidation of the town’s buildings – exacerbated by the ‘Great Fire’ of 1791. As a ‘potwalloper’ borough, Minehead’s franchise lay in the inhabitant householders (i.e. those who could boil – or ‘wallop’ – pots on hearths in their houses). To complicate matters, the borough was composed of three tithings (a sub-unit of a parish) which confusingly corresponded with parts of the parishes of Minehead and Dunster. Therefore, to qualify as a voter, along with the usual requirements of being an adult male, one also had to be a parishioner of Minehead or Dunster, a housekeeper (i.e. the occupier of a house) within one of the three tithings, and not in receipt of alms.

There were therefore four main directions from which a Minehead elector’s right to vote could be challenged. Were they over 21? Were they in receipt of alms? Were they a settled parishioner? Were they a legal housekeeper? However, there were dozens of grounds on which these last two points could be disputed. Had they served an apprenticeship in another parish? Did they live separately from their family? Had they lived in their house for less than 40 days prior to the election or, after 1786, six months? And so on.

The pre-election canvass was a crucial opportunity to gather information on voters. In Minehead, candidates’ agents travelled from door-to-door to solicit votes, but also to gather information on the legitimacy of potential voters. In 1747, for example, the agents of Percy Wyndham O’Brien marked one voter as ‘No Friend. – query vote as not being a housekeeper’, and wrote next to another, ‘Query vote he’s had relief’. As the preface of ‘No Friend’ implies, O’Brien’s canvassers sought to identify and subsequently disqualify individuals who would vote against him – while also collecting evidence to protect the votes of his supporters. By the end of the eighteenth century, election agents had developed more sophisticated methods. In preparation for the elections of 1796 and 1802, John Fownes Luttrell’s agents listed every townsman alongside both ‘Proofs to Support’ and ‘Proofs to Disqualify’ their votes. Where the voter’s intentions were unclear, notes would be added to both columns.

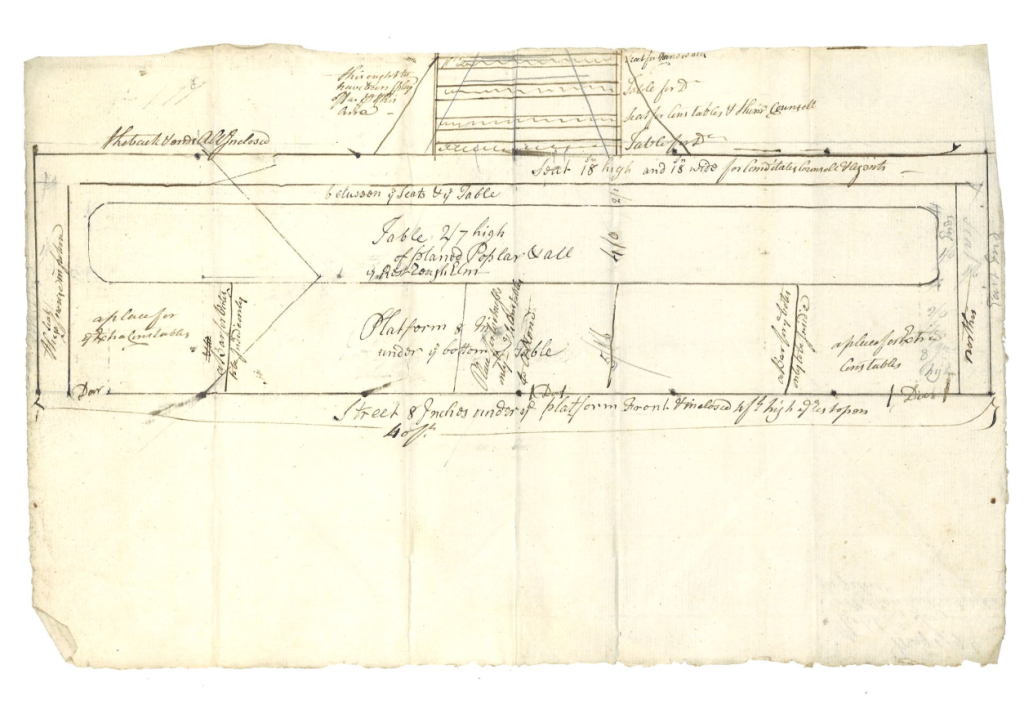

When an election came around, voting took place at specially-constructed polling booths. It was here that each elector was required to swear oaths and declare their votes, but also where votes could be objected to and challenged by the candidates’ agents and attorneys. In most cases, witnesses were called upon to ascertain whether or not a vote was valid. Often this was prearranged before the poll began: men and women, voters and non-voters alike, would be summoned to the hustings to present documentation or reveal their interactions with voters. These were frequently older residents who acted as ‘repositories of electoral memory’ (to use Elaine Chalus’s phrase), and could speak to particular families, living arrangements, or past voting customs.

A minute book detailing the Minehead elections of 1796 and 1802 shines a fascinating light on this process, giving a voice to many witnesses – albeit as summarised by a clerk. In an effort to prove that William Jones (a Luttrell supporter) had not been resident in his house for six months prior to the general election of July 1802, Mark Coles alleged that Jones’s bed had been removed at Christmas to ‘give room for a Dance’. This was refuted by Ann Cann, who attested to the fact that Jones had ‘eat, drank & slept in his house for 6 months past’. However, Cann’s evidence was discredited by both weight of numbers and a misogynistic slight on her manner at the hustings; one Mr Blake dismissed her words as ‘a frenzy’ and claimed she had not visited the house with the past six months. As a result, Jones’ vote was rejected.

At the same election, a different Luttrell voter survived an objection. The opposing attorney sought to disqualify John Widlake as not being a housekeeper, since he lived separately from his family. Several female witnesses – including a former employee – confirmed that Widlake’s wife lived and had been ‘brought to bed’ at a place called Lang’s House, while Widlake lived with his mother. It was one Mrs. Jones who provided the full story: upon his return to Minehead from Bristol, Widlake had moved in with his mother, but as he had ‘married against his mother’s consent… she never would suffer [his] wife to come there’. Despite this personal revelation, Luttrell’s agents successfully defended Widlake’s right to vote because he had paid the rent for his mother’s house.

Potential voters would try various methods to qualify for a vote ahead of an election. One common practice involved ‘splitting’ houses whereby the rule of ‘one housekeeper per household’ could be circumvented by dividing the house into separate apartments with their own front doors and cooking arrangements. Especially scandalous were the votes tendered by William Fry and Joseph Hurford, who each lived in one half of an old barn divided with ‘rough planks’ without ceilings or chambers. One witness was asked, ‘do you know where this miserable wretch lives?’, replying, ‘in the Barn with the Rats’. The questioning attorney raged at Fry as a man ‘degraded & debased from man to beast’ who was ‘unworthy to give his vote’. Despite his best efforts, the Returning Officers accepted the votes.

Such examples highlight the ambiguous divide between who could and who could not participate in eighteenth-century parliamentary elections. The fact that non-voters could play an influential role as witnesses serves as a reminder of the substantial social ‘reach’ of elections. Through their memories of people and places, they were important political actors.

Today, some governments, including the UK, are proposing to introduce of voter ID requirements into elections, and it is tempting to draw parallels between modern voter requirements and the eighteenth century. Such parallels should not be taken too far. Qualifications to vote in the eighteenth century were often so complex that attempts to challenge individual voters’ right to poll became a routine feature of elections. Minehead serves as an excellent example of how local custom, tradition, and precedent were interweaved throughout the opaque Georgian electoral system, creating huge scope for challenge, disagreement, and differing legal interpretations over individual votes. Critics of modern voter ID requirements have framed it as a barrier to democratic participation which will disproportionately impact more marginalised members of society. While this was also true in the eighteenth century (remember the ‘miserable wretch in the Barn with the rats’), challenging votes at the hustings also allowed non-voters to participate in the electoral process by acting as witnesses: legitimising or discrediting votes and, by extension, influencing the outcomes of elections.

Further Reading

Chalus, Elaine, ‘Women, Electoral Privilege and Practice in the Eighteenth Century’, in Women in British Politics: The Power of the Petticoat, ed. Catherine Gleadle and Sarah Richardson (Basingstoke, 2000), 19–38.

Dyndor, Zoe, ‘Widows, Wives and Witnesses: Women and their Involvement in the 1768 Northampton Borough Parliamentary Election’, Parliamentary History, xxx (2011), 309–323.

Somerset Heritage Centre, DD/L, Luttrell Family of Dunster Papers.