Find out how dancing was used to mobilize voters and their families.

[5-minute read]

In eighteenth-century elections, candidates were not just assessed on their speeches and campaign promises, they were also measured by the way they carried themselves, whether on the hustings or in the ballroom. While dancing may seem like an activity designed solely for entertainment, it was actually a vital political tool used by candidates and their patrons to treat their constituents (Figure 1).

For candidates, hosting balls and dancing with the community was intended to forge stronger bonds with voters and their families, to build social cohesion and citizenship. The timing of an election ball and its intended political impact were linked. Balls held before elections were orchestrated to maintain influence over the electoral interest. In September 1773, Lady Chatham (wife of the former Prime Minister, William Pitt the Elder) wrote to her nephew’s wife, Anne Pitt, of her surprise to hear of Thomas Pitt of Boconnoc dancing. Lady Chatham hoped that,

… the Ladies were duely sensible of their obligation on the occasion, and that it will be remember’d at a proper time … for I assure you it is only an innocent election that they are wish’d to contribute to.[1]

The honour of dancing with Mr Pitt (MP for Okehampton, then Old Sarum, and later 1st Baron Camelford) generated an unspoken obligation over twelve months before the general election, which ran from 5 October to 10 November 1774. Even though Thomas Pitt stood for Old Sarum, one of England’s rotten boroughs (in which the Pitts of Boconnoc owned the borough’s burgages), an election ball was held to maintain goodwill with the burgage holders and their families.[2]

Elite families also endorsed candidates by hosting and attending suppers and balls held in their honour. Women in particular were courted for their influence within their family circles, and were engaged in campaigning at home, in the streets, in the ballroom. The duchess of Devonshire was actively involved in creating, supporting, and making visible the Cavendish family’s networks. In a letter to her mother, Lady Spencer, from 9 October 1774, she wrote about Derby’s election ball, where Thomas Coke stood as a candidate for his father Wenman Coke (MP for Derby and later Norfolk):

We met [Lord Frederick Cavendish, the Duke’s uncle] on the stairs extremely drunk, and I stood up with young Mr Coke for almost ten minutes in the middle of the room before they could wake the musick to play a minuet, and when they did play they all of them play’d different parts. I danced country dances with Mr Coke, but as nobody was refus’d at the door of the ballroom was quite full of the daughters and wives of all voters, in check’d aprons &c. Mr Coke, the father, is gone to be chosen for Norfolk, and, it is said, he intends at the meeting of Parliament, when he must make his option between Norfolk and Derby, to give up Derby…[3]

Success hinged on the Duchess’s performance, for, although the 5th duke of Devonshire was reported to be ‘[…] an amiable and respectable character […] dancing [was] not his forte’.[4] The duke, lacking his wife’s dancing aptitude, benefitted from her celebrity, an asset for strengthening his social and political interests. Her attention, through conversation and dancing, was expected to confer value on the candidate.

In boroughs and counties where the result of an election was not already determined, election balls were used to gauge a constituency’s interest (Figure 2). For John Courtney, attending an election ball was an indication of support on behalf of the voter. Leading up to the 1761 general election, Michael Newton and George Forster Tufnell stood as candidates for the borough of Beverley in Yorkshire. Prior to the election in March 1761, a ball was held in December 1760 for George Tufnell’s supporters. John Courtney was invited but did not attend in deference to his uncle’s voting intentions.[5] Despite declaring his lack of support for Mr Tufnell, the candidate delayed the opening of the ball in hopes that Mr Courtney would arrive, and was surprised that he did not attend.[6] Attendance at the election ball consequently served as an opportunity to gain and measure support within the community.

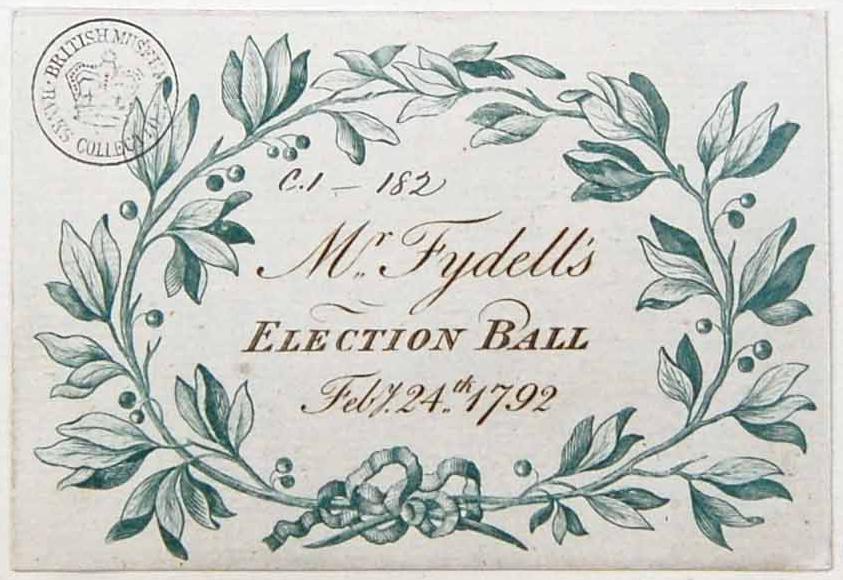

Alongside accounts of elections in newspapers, correspondence, and memoirs, literature and caricatures can also be used to explore electoral culture. Sir Hyacinth O’Brien, in Maria Edgeworth’s c.1811 novel Rosanna, used dance as a canvassing tool, inviting the Gray family to attend his election ball. It was useful for candidates to court women’s favour during the electoral campaign as doing so could translate into the acquisition of enthusiastic and vocal supporters both at home and in the streets (Figure 2). Votes were frequently viewed as family property, and not based solely on the inclination of the male voter, providing women more active roles within the franchise.[7] Critically, Sir Hyacinth O’Brien left the invitations with the daughter of the house, knowing ‘she was all to her father and brothers, and of course could and would secure their votes, if properly spoke to’.[8] The invitation was followed up by a visit from the candidate to assess their support (although the Grays were not swayed by the honour of this invitation to bestow their votes).[9] The election ball invitation below (Figure 3) is connected to Thomas Fydell, who had been elected for Boston, Lincolnshire in 1790. Election balls were one of the political tools used to court constituents, whether staunch supporters or undecided.

Post-election balls celebrated the prevailing candidates and expressed their gratitude. During the 1784 general election, Charles James Fox and Samuel Hood were elected for Westminster. Following the results of the poll, Mrs. Crewe (wife of John Crewe, MP for Cheshire) held a spectacular ball in London for Charles James Fox ‘in commemoration of the victory obtained over Ministers in Covent Garden’.[10] John Crewe had been a long-term supporter of Charles James Fox both in government during the Fox-North coalition and in opposition, supporting him financially with the hope of being made a peer.[11] Mrs Crewe’s ball was an opportunity for Fox’s staunchest supporters to congregate and celebrate their political beliefs in solidarity.

Not only was the post-election ball used to thank voters for their support, but it also provided an opportunity for voters to be reunited after contentious, rowdy, or divisive election proceedings. During the 1761 general election in Beverley, George Tufnell held a ball in December 1760 to win supporters (as explored above), but he also held one following his successful election in March 1761.[12] John Courtney had once again been invited, but missed the ball due to illness. Mr Courtney showed reluctance in attending the ball during the campaign as an indication of support for his uncle’s electoral interest. Following the result of the poll, however, he ‘shook hands, and […] wishe[d] Mr Tufnell joy. I had a great cold he might hear by my voice, so he might not think it strange I was not as his ball last night’.[13] These celebratory balls were intended to help mend the social and political divisions brought about by the campaign, bringing together constituents to celebrate their citizenship and their elected representatives.

Regardless of whether a first-time election or subsequent return to Westminster, convention obliged the MP to host an election ball. Despite having returned without opposition in Liverpool in 1774, Sir William Meredith and Richard Pennant (long-term MPs for the constituency) nonetheless held a ball for 300 ladies and gentlemen.[14] This apparently unnecessary expense can be reframed as a political investment, renewing, consolidating, and maintaining the freemen and their families’ support for future elections.

On Monday the 10th inst. came on the election for members for Liverpool, when the Right Hon. Sir William Meredith, Bart. And Richard Pennant, Esq; the late worthy members, were returned without opposition, Thomas Butterworth Bayley, Esq; having declined a few days before. The two following days the Freemen were plentifully regaled, and on Wednesday a ball and cold collation was given by the members to near 300 gentlemen and ladies, which was elegantly and splendidly conducted.[15]

The ballroom was not just a space for flirtation and entertainment, but for canvassing and treating the voters and their families throughout the electoral process. The timing of Georgian election balls was significant to their purpose, whether to sway the public to a candidate’s cause or to express post-election gratitude. Election balls were civic events that rallied the citizens around the MP, celebrating their citizenship. The ballroom itself enabled elite families and candidates to amass social capital and political credit, while dance contributed to establishing reputation and strengthening networks.

[1] London, British Library, Add MS 59490 ff.10d-11, Letter from Lady Chatham to Anne Pitt, 13 September 1773.

[2] J. Brooke, ‘Old Sarum’, History of Parliament Online (2020) <https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1754-1790/constituencies/old-sarum> [accessed 1 November 2022]

[3] Georgiana Cavendish, Georgiana; extracts from the correspondence of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (London, 1955), 16.

[4] Whitehall Evening Post [London] (28 March 1782), p.3 col. c.

[5] John Courtney, The Diary of a Yorkshire Gentleman: John Courtney of Beverley, 1759-1768, ed. by Susan Neave and David Neave (Otley: Smith Settle, Ltd., 2001), 32.

[6] Courtney, 32.

[7] Kathryn Gleadle, Borderline Citizens: Women, Gender and Political Culture in Britain, 1815-1867 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 26.

[8] Maria Edgeworth, Rosanna (London, 1811), 137.

[9] Edgeworth, 134-5.

[10] Nathaniel Wraxall, The Historical and Posthumous Memoirs of Sir Nathaniel William Wraxall, 1772-1784 (London, 1884), 349-51.

[11] Mary Drummond, ‘Crewe, John (1742-1829, of Crewe Hall, Cheshire’, History of Parliament Online (2020) <https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1754-1790/member/crewe-john-1742-1829> [accessed 1 November 2022]; Josiah C. Wedgwood, Staffordshire Parliamentary History, From the the Earliest Times to the Present Day, 3 vols (William Salt Archaeological Society, 1919-1922), II, 306.

[12] Courtney, 39.

[13] Courtney, 39.

[14] Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser (18 October 1774), p.3 col a.

[15] Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser (18 October 1774), p.3 col a.