Disputed results were common, often taking months of legal wrangling to resolve

[10-minute read]

The majority of eighteenth-century elections went uncontested, which is to say that an agreement had been reached in the constituency not to put up rival candidates, allowing the nominated candidates to be returned unopposed. However, when an opposition did materialise, and a poll actually took place, the result was very likely to be disputed. Perhaps this is unsurprising, given the cost of running a campaign (expensive then, as now), as well as the reputational damage that defeat could cause. According to Frank O’Gorman, between 1715 and 1741 (for instance) roughly 70% of contested election results were officially challenged. Between 1774 and 1831, it was still around 55%.

On what grounds were election results challenged?

In the twenty-first century, allegations of voter fraud hinge on everything from absentee ballots, to deceased voters, to controversy surrounding Sharpie pens. In eighteenth-century England, defeated candidates could challenge a result on similarly varied grounds. The bewildering array of franchises within constituencies (i.e. the rules which determined who had a legal right to vote) were a fertile source of contention. A frequent complaint was that the returning officer (who presided over the poll and ensured its validity) had been partial in favour of the victorious candidates – for example, he may have been accused of admitting unqualified voters, or pre-emptively closing the poll before all of the electors had been polled. Other common complaints rested on the conduct of the election process: allegations of bribery and corruption were rife (not without reason), and elections were occasionally the sites of full-scale riots.

How were votes challenged during the poll?

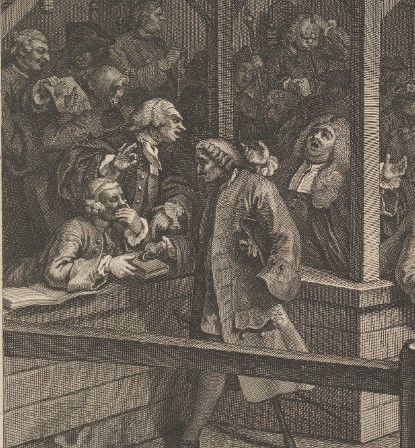

An eighteenth-century election could be disputed at several points in the electoral process. During the course of the public polling a particular individual’s right to vote could be challenged by the agents of any candidate, with the exact process varying from place to place. In 1768, more than half of the voters in Northampton were required to present witnesses (local men and women) at the hustings to prove their right to vote. Other constituencies dealt with disputed voters following the conclusion of the poll, as in the 1784 Bedfordshire election. As electioneering become more professionalised over the course of the century, candidates increasingly employed counsel to appear on their behalf at the hustings in order to raise objections against voters. Lawyers challenging an ex-soldier’s right to vote, for example, are shown in Hogarth’s polling scene from The Humours of an Election.

How was an election result challenged?

After a result had been declared, the defeated candidate could immediately demand a ‘scrutiny’ to challenge the legitimacy of the outcome and to look into the credentials of voters – although these requests were often denied. The practicalities of examining hundreds or even thousands of individual votes before the commencement of the new parliament made scrutinies highly ineffective, and they rarely unseated successful candidates. In the Westminster election of 1784, Charles James Fox was accused of ‘polling all the Roman Catholic hairdressers, cooks, &c.’, and the defeated candidate swiftly demanded a scrutiny. With the returning officer refusing to declare a legitimate victor until he had completed the tortuous process of examining all of Westminster’s 12,000 or so voters, the constituency was left unrepresented for more than eight months.

Petitioning the House of Commons

The ultimate arbitrator of disputed elections was the House of Commons. Each new parliament was accompanied by a flurry of petitions, by far the most common way in which defeated candidates challenged election results. In 1705, 31 petitions were lodged and read at the bar of the House; this rose to a high point of 99 in 1722, before falling away. Although some petitions were heard at the bar, most were referred to the Committee of Privileges and Elections (which was essentially a ‘Committee of the Whole’).

The Committee ostensibly determined petitions on their merits, but its membership reflected the wider balance of power between Government and Opposition in the House, and it was used for political purposes by the largest party to unseat opposition MPs and elect their own supporters. As early as 1702 it was described as ‘the most corrupt council in Christendom’. Between 1715 and 1754, 70% of petitions from candidates supportive of the opposition were simply never heard.

It was under the Whig Sir Robert Walpole (often regarded as Britain’s first Prime Minister) that the Committee was used most flagrantly for partisan ends: it was claimed that Walpole could ‘by the very nod of his head’ carry decisions on controverted elections. It was partly this manipulation of the Committee which provoked the downturn in the number of election petitions following the 1727 election, as Tories increasingly viewed the whole process as futile.

Nonetheless, maintaining control of the Committee required careful management. Members were pressured into attending votes by party leaders (or risk being labelled a ‘slinker’), and heated debates could carry on into the small hours of the morning. A particularly fiery exchange over the Cambridgeshire election of 1698 resulted in two MPs from rival parties duelling in St. James’s Square at night – one combatant wounded the other, broke his sword, and promptly returned to the Committee.

In order to maintain control, it was important for the largest party to secure the Chairmanship of the Committee. When the opposition successfully secured the post in 1741, the Members began to cry ‘Huzza!’ and ‘Victory’ – a chant which was heard and repeated by the crowd in the lobby, and subsequently by ‘those in the Court of Requests, the coffee houses and the streets’.

Attempts to reform the petitioning process made some progress in 1770, when the Parliamentary Elections Act (10 Geo. III c. 16) – known as the Grenville Act – determined that petitions would be heard before an impartial Select Committee of 15 Members. These committees were responsible for determining complex legal questions relating to election disputes: depending on the allegations, they would preside over the examination and cross-examination of witnesses to bribery or voter fraud, or assess each individual vote challenged by the defeated candidate. This was, however, a slow and expensive process, which many unsuccessful candidates decided not to pursue.

Controverted elections and the ‘people’

Although the majority of the population were disenfranchised, they could nevertheless find ways to participate in the process of disputing election results. Witnesses travelled to London to present their evidence to Parliament (often at considerable expense to candidates), and records of their testimonies provide a fascinating insight into the role played by figures who are frequently absent from the historical record (often women). These witnesses could use their testimonies as an opportunity to air local grievances, and provided a crucial link between parliamentary and local political cultures.

Outside of the courtroom, a swathe of popular printed texts shared the latest developments from election disputes with the wider public. An attentiveness to this wider context of popular political participation can allow us to put the ‘people’ back into politics.

The complex and multifaceted process of challenging election results in the eighteenth century therefore encourages historians to extend the timeframe of ‘an election’ – which began long before the first vote was cast, and was rarely decided when the poll closed. It also makes us extend our understanding of the social depth of elections.

A version of this article first appeared as a Hansard Society blog post, written in the context of challenges to the result of the 2019 US presidential election.

Further Reading

Elaine Chalus, ‘Gender, Place and Power: Controverted Elections in Late Georgian England’, in James Daybell and Svante Norrhem (eds.), Gender and Political Culture in Early Modern Europe, 1400–1800 (London, 2016), 179–96

Zoe Dyndor, ‘Widows, Wives and Witnesses: Women and their Involvement in the 1768 Northampton Borough Parliamentary Election’, Parliamentary History, 30 (2011), 309–23

W. A. Speck, ‘“The Most Corrupt Council in Christendom”: Decisions on Controverted Elections, 1702–42,’ in Clyve Jones (ed.), Party and Management in Parliament, 1660–1784 (Leicester, 1984), 107–21