Standing as an MP was an expensive undertaking. Success often needed to be bought [15-minute read]

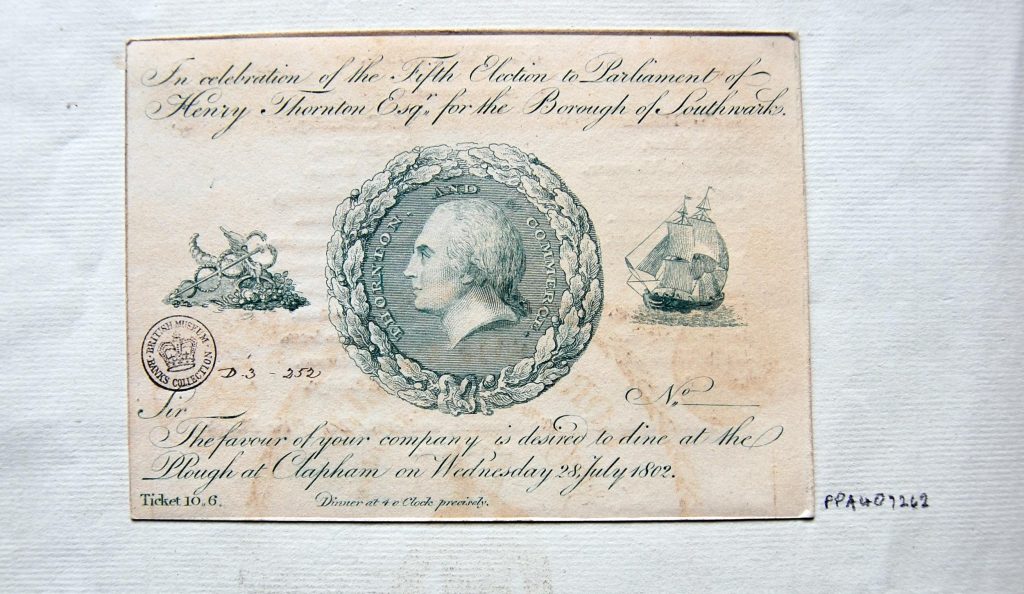

The costs of campaigning remain expensive today, as they were in the eighteenth century. Over the course of centuries, however, the types of expenditures have shifted dramatically. In the eighteenth century, food and drink were key for ‘treating’ the electorate in the weeks and months before an election. In order to win over voters, candidates often provided ‘treats’ for their constituents, distributing food and drink, or even fuel to those in need, and hosting dinners and balls to entertain and generate goodwill within the community. This could be true even when there was no actual contestation of the election. Purchasing and distributing ‘favours’; donating to local institutions; paying for advertisements in the press; and retaining lawyers, election agents, musicians, bell ringers, and carriers were all vital parts of the infrastructure and activity of Georgian elections.

Most of these expenses had to be borne by the candidates themselves, or their supporters by subscription. However, the Government (via the king and Prime Minister) were also actively engaged in backing their candidates financially, so as to secure Parliamentary support. In Westminster in 1774, the 22-year-old Lord Thomas Pelham Clinton (son of the 2nd duke of Newcastle) was supported by George III and put forward by Prime Minister Lord North, whose government paid for all election expenses for Clinton. Lord North reported to the duke of Newcastle that, ‘I never knew the King more earnest on any point. He has been informed of the great probability of your son’s success, and dreads nothing so much as the reputation of abandoning so fair a prospect from the dread of noise, riot, and scurrility. … We will take all the trouble of the canvass off your Grace’s hands’.[1] In James Gillray’s 1788 caricature, Election Troops Bringing in their Accounts to the Pay Table, the Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger is depicted behind the bars of the Treasury, addressing soldiers, cobblers, sailors and women wearing the favours of Baron Hood in their bonnets and tricorn hats. They can be seen bringing receipts ‘for voting 3 times’, ‘for singing ballads’, ‘for Eating & Drink for Jack Ass Boys’, for hiring ‘Grub Street Writers’, and writing puffs and squibs (many typical election expenses for candidates to pay). Pitt the Younger addresses them saying, ‘I know nothing of you, my Friends. Lord [Hood] pays all the expences [sic] himself – Hush! Hush! Go to the back-door in Great George Street under the Rose’, alluding to underhand payments from the Government itself, symbolised by the rose.

Engagement of Community

Even the infrastructure and management of elections was chargeable to the candidates. For instance, the under-sheriff’s account for the 1807 Yorkshire election reveals payments made for the serjeants and 112 special constables, as well as the country clerks, poll clerks, and deputy sheriffs who administered the election. The under-sheriff then tabulated these expenses and distributed them to the candidates for payment. Alongside the election officials are also payments to Mr Watson, a joiner, ‘for fifty constables’ staves, and boards for inscriptions on the booths’; to Mr Parkinson, a painter, ‘for painting the boards and inscriptions’; and to Mr Wolstenholme, a stationer, who provided poll books, inkstands, pens, paper, and oil cloths for the poll booths.[2] The poll booths themselves were likely to have been constructed by Mr Halfpenny, Mr Stones, Mr Kimber, and Mr Carlton (joiner, cabinet makers, and tinsmith), revealing how local tradesmen and artisans were commissioned to build the electoral infrastructure required to accommodate over 23,000 voters for Yorkshire in 1807. Receipts can be used to tease out behaviours and objects associated with campaigning that may not have survived over the intervening centuries.

Election Entertainments

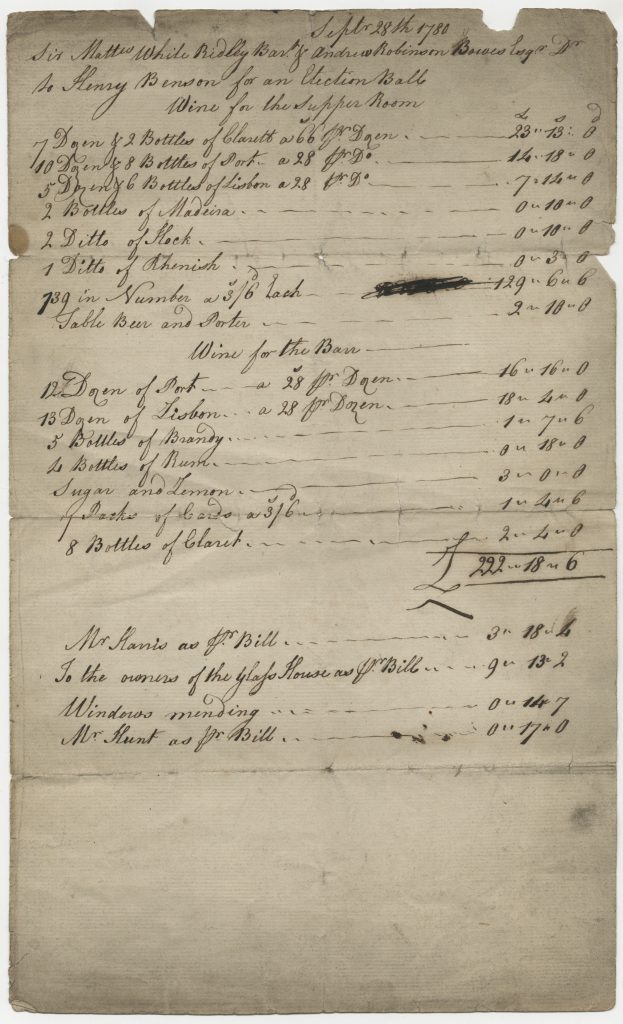

Food was a staple of electoral treating. Dinners and entertainments were in fact often an expected part of canvassing support and securing votes. In Buckinghamshire in 1779, during the by-election which followed George Grenville’s elevation to the House of Lords as Lord Temple, the Grenville family campaigned for George Grenville’s younger brother, Thomas, to fill his seat. The by-election was uncontested, but four entertainments were held from 25 September to 8 October 1779 prior to Thomas Grenville’s election on 25 October, after which he held two more dinners to thank his supporters on 25 October and 4 November.[3] Together, the six entertainments cost an eye-watering £127 13s. 9d., even though the result of the election was never in question. However, it was beneficial to maintain the family’s social credit within the community, to be called upon during future contests. The following year, in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Sir Matthew White Ridley and Andrew Robinson Bowes jointly held a ball on 28 September 1780 at the assembly rooms for 750 constituents, celebrating their successful return.[4] The receipt survives in the Northumberland Record Office giving details of the amount of wine, ale, and spirits provided for the supper room and bar, totalling £223 14s. 6d. for 602 bottles of claret, port, Lisbon, Madeira, Hock, Rhenish, Brandy, and Rum; and unspecified quantities of beer and porter.[5] These sorts of expenses were not considered as corrupt, but were the expected sorts of activities demonstrating conventional electoral deference to the voters by the candidates. These expenses only outline the amount of alcohol purchased for this event, not including payments for food, musicians, or lighting.

From the receipt for the election ball, we can also start to outline some of the other activities taking place at the Newcastle assembly rooms. Purchases of rum or brandy, sugar and lemons likely meant that punch was made and served to refresh the dancers and guests in the heat of the ballroom. The fact that Sir Matthew White Ridley also paid for seven packs of cards, at 3s. 6d. each, indicates that card tables had been set up for non-dancers and that card games — and probably some gambling —also took place at the ball. Intriguingly, a line at the bottom of the page indicates a sum to be paid ‘to the owners of the Glass House’ for £9 13s. 2d. While it is unclear what specifically this sum was for, as Newcastle was a centre of glass manufacturing in the eighteenth century, it is possible that this expense was for fancy, commemorative glassware to celebrate the election. The receipt also lists 14s. 7d. for ‘windows mending’, suggesting that either the windows in the assembly room needed attention prior to hosting the ball (in which case this would have effectively been a candidate providing a public service), or there may have been some rowdy, drunken behaviour and damage to property following the election ball that evening.

Inns and taverns were key places within towns and cities for electoral activity, being the locations of election headquarters for different candidates and the venue for dinners and balls.[6] During the 1784 Westminster election, for example, Wood’s Hotel in the piazza of Covent Garden served as the headquarters and committee rooms for Sir Cecil Wray and Baron Hood, while the Shakespeare’s Head Tavern in nearby Wych Street provided a hub of activity for Charles Fox and his supporters. Certain areas of towns upheld allegiance to individual parties and candidates, and innkeepers themselves frequently had connections with the local gentry.[7] Candidates and patrons promptly made arrangements with the taverns in the town to host their followers. They often split the town between them; however, there were also some publicans who appeared to supply food and drink to the supporters of specific candidates without a formal agreement. Inn owners were also actively involved in the campaign, providing food, beds, and places for the candidate to treat, offering rooms that served as committee rooms, and serving as election ball stewards. Food and drink were the primary means of treating constituents. The Sun Tavern in Shrewsbury provided a receipt for all the breakfasts and dinners — for 443 people and dinners for 1,265 guests — provided for electors over the course of the campaign, an ‘arduous struggle’ which ran from 31 May to 8 June 1796, although it is unclear whether these expenses were linked with a longer period of unofficial canvassing prior to the election.[8] In 1796, the Sun Tavern provided breakfasts for 443 people and dinners for 1265 guests.[9] The Sun’s most significant expenditures, however, were on 3,039 gallons of cider and ale at £279 14s. 9d. for the local constituents

| £ | s. | d. | ||

| 443 | Breakfasts | 14 | 5 | 4 |

| 572 | Bread and Cheese | 8 | 16 | 4 |

| 1265 | Dinners | 89 | 1 | 0 |

| 1164 | Gallons of Cider | 117 | 8 | 6 |

| 1875 | Gallons of Ale | 162 | 6 | 3 |

| Rum | 1 | 6 | 4 | |

| Tobacco | 6 | 12 | 3 | |

| Gin ‘for Constables’ | 0 | 5 | 6 | |

| Miscellaneous expenses | 0 | 19 | 10 | |

| 401 | 1 | 4 |

Favours

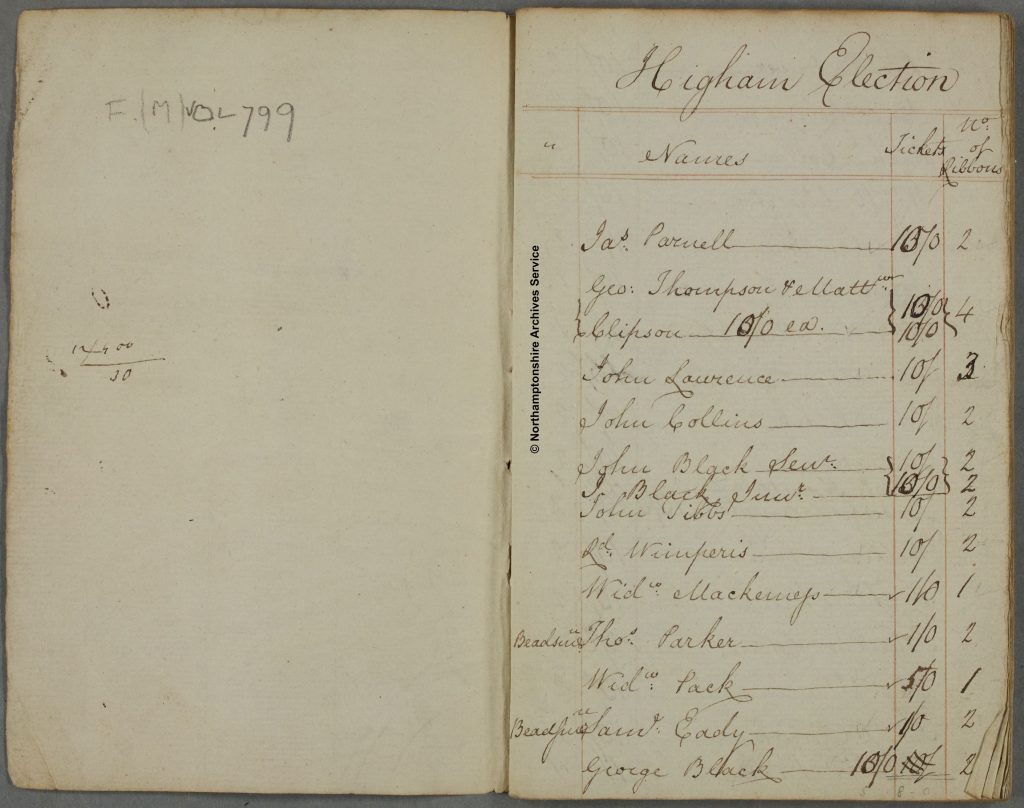

Favours were publicly worn by supporters – whether eligible to vote or not – to indicate their political allegiance and persuade others to join them. While agents and local shopkeepers produced and distributed ribbons, cockades and other favours in the candidates’ colours, cockades could also be made at home by women and servants. Election colours were not fixed yet in party terms during the eighteenth century. During the 1807 Yorkshire election, the choice of colours was highly politicised. Lord Milton selected orange, a colour associated with Protestantism and the 1688 Glorious Revolution and Whiggery. Henry Lascelles, a ministerial candidate, chose blue as his campaign colour, a colour associated with the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots in 1780, while William Wilberforce opted for the more neutral colour pink for his campaign. While Tories were usually ‘true blue’, and the Whigs from early eighteenth century had a tendency to use orange (as did Pitt the Younger and his compatriots in the Constitutional Club during the Regency Crisis), many candidates actually appeared to have used their hunting colours. For the April 1784 Buckinghamshire election, in which the Pittite candidates William Wyndham Grenville and John Aubrey ran against the Foxite Lord Verney, Grenville paid Mr Nash 16s. for painting and gilding the flag for his campaign. He also paid for 114 green favours for £5 14s. and 18 additional (and more expensive) favours with gold mottos to be distributed to the mayor and aldermen of Wycombe for £2 5s., a visual indicator of their civic roles.[10] In Higham Ferrers in Northamptonshire (the pocket borough of the marquess of Rockingham and later Earl Fitzwilliam), elections were uncontested from 1724 to 1832 (when the borough was disenfranchised). Despite the lack of any contest, ribbons were still produced and distributed as favours to the constituents.

The account book for the elections from 1818 to 1822 includes invitation lists for the dinners at the Queen’s Head, and suppers and teas for the ladies held during William Plumer’s campaign; however, it also records the number of ribbons distributed to each person who purchased tickets.[11] 443 ribbons were distributed in 1818 to 287 men and women, who passed them along to family and friends to indicate their support for Plumer. Others were distributed to ‘ringers’ (presumably to ring the church bells) and ‘carriers’ (perhaps to carry banners, or to ‘chair’ the elected candidates). Other commemorative favours could include mugs, teapots, jugs, or glassware, handkerchiefs, tokens, and even bobbins. Efforts to crack down on the use of partisan colours and favours were made in the early nineteenth century. By 1827, an Act of Parliament forbade the distribution and wearing of partisan cockades and ribbons, hoping to reduce electoral violence.[12] However, the practice of wearing a candidate’s colours was so central to popular participation that it remained difficult to enforce.[13]

Civic and Charitable activity

Election funds were also allocated for gift-giving and charitable activities to develop a sense of obligation and gratitude towards the candidate for supporting community infrastructure and disadvantaged constituents. In Bedfordshire, John Harvey of Ickwell Bury ran in harness with Sir Pynsent Chernock in the 1715 general election. These Tory candidates supported local causes to generate support for their campaigns, one of which included funding the purchase of an organ for St Paul’s church in Bedford.[14] Similarly, during his tenure as MP for Stafford in 1784, Richard Brinsley Sheridan used charitable donations to generate goodwill within the community during electoral campaigns and in the intervening years between elections. He contributed towards the local infirmary, providing £5 5s. for its subscription, as well as a further £2 2s. to help relieve clergymen’s widows.[15] Meanwhile in Northampton in 1768, Lords Spencer, Halifax and Northampton made significant donations within the community, spending a substantial amount of money on bolstering the town’s infrastructure through the procurment of locks for its canal network.[16]

Ephemeral activity

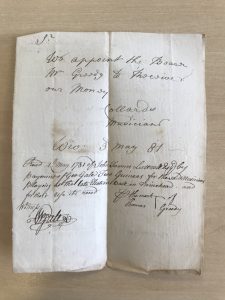

Election receipts are also a useful source for uncovering ephemeral sounds, activities, and behaviours of Georgian elections. A receipt for the by-election for Buckingham in 1753 reveals that a drummer and two fiddlers were hired at 2s. 6d. per musician, probably to participate in the chairing procession through the town. Even an uncontested election like this would also have featured the sounds of bells ringing from the church and throughout the town, as we know that bell ringers were hired at £1 1s. and criers were paid to proclaim the result throughout the town.[17] A 1715 burlesque ‘Bill of Costs’ supposedly setting out the costs of ‘a late Tory election in the West’, though intended as a satire, also tells us something about electoral soundscapes, with ‘roarers of the word “Church”’ and ‘a set of ‘No Roundhead’ roarers and ‘coffee-house praters’ paid £40 each.[18] These activities were by no means peripheral to electioneering, but the performances of musicians, the chants of crowds, and the pealing of bells themselves leave little physical trace in the archives.

Publications

Political patrons and candidates would also often pay for printing, either as part of their campaign or afterwards. It was common to insert reports and exhortations into the local newspapers, as well as to publish handbills, speeches, squibs, and ballads during the campaign. They might also fund statements of gratitude to their voters after the election, as well as further reports and sometimes poll books. A receipt from 1769 reveals that the Grenville and Verney families kept news of the Buckinghamshire petition in the press in July and in September when the resolutions were published. Advertisements about the Buckinghamshire Grand Jury and petition resolutions were published widely — in the St James’s Chronicle, The Times, London Evening Post, General Evening Post, Whitehall Evening Post, London Chronicle, Lloyds Weekly Newspaper, Daily Gazetteer, and the Public Advertiser for 18s. for each entry.[19] For the Yorkshire election of 1784, the Fitzwilliam interest paid £231 13s. 3d. for printed handbills and advertisements in the press.[20]

Twenty-three years later in 1807, Yorkshire’s under-Sheriff recounted that the plan for printing the poll book from that most expensive of pre-Reform elections was proposed by Lord Milton’s election committee.[21] Lord Milton’s campaign during the 1807 election was notable for the number of plumpers who voted for him (81.6 per cent, or 9061 of 11,177 of votes, plumped for Lord Milton during the campaign, in comparison with 10 per cent for Wilberforce and 16.7 per cent for Lascelles). The publication of the poll book would have consequently preserved for public record the significant electoral victory by Lord Milton and the Fitzwilliam interest in the largest constituency in the country. While the poll book was of interest to the candidates themselves, since they could be used for future canvasses, poll books were also of interest to the public who were eager to see the record of how they and their neighbours had voted.[22] The publication of the poll books consequently had an afterlife, likely swaying the creation or shifting or local networks, and determining with whom local tradespeople did business.

Treating Legislation

The cost of an election, including the requisite treating and bribery imposed a significant financial strain on political patrons and candidates. The cost of some elections led to several families withdrawing from their attempts to secure seats in parliament due to their inability to finance another campaign. The 1768 election changed the balance of power in Northampton for instance, as the earl of Halifax was financially ruined by the expense of the contest, withdrawing from Northampton’s politics entirely. In Northumberland in 1826, Lord Grey sold Ulgham Grange to finance the 1826 by-election and general election for his son. Lord Grey estimated that the overall cost of the election for the county of Northumberland was an astonishing £187,681.

The offering of ‘treats’ was increasingly of concern in the early nineteenth century, criticized by those seeking to encourage the ‘purity’ of elections. In 1806, an Election Treating Bill was read, debating the practice of providing food, drink and transport to voters. Ultimately, the bill was not passed. Treating was once more debated in 1840, ultimately affirming that voters who lost a day of work to vote ought to be compensated with food and drink. The conventions of food, drink, and cockades were so central to the visual and material identity of Georgian elections that election expenses remained inflated until the 1883 Corrupt and Illegal Practices Act which resulted in the significant decline in candidates’ election expenses.

[1] Newcastle [Clumber] Mss.

[2] Jonathan Gray, An Account of the Manner of Proceeding at the Contested Election for Yorkshire in 1807 (York, 1818), 42-4.

[3] Huntington Library, San Marino, California, mssSTG Stowe Grenville Elections Box 1(11).

[4] Newcastle Courant (30 September 1780), p.4 col.b.

[5] Northumberland Archives, Expenses of an Election Ball: Sir M.W. Ridley and A.R. Bowes Esq., 1780, ZRI/25/9.

[6] G. Leveson Gower, Private Correspondence, 1781 to 1821 (London, 1916), I, 98-9.

[7] Frank O’Gorman, ‘Ritual Aspects of Popular Politics in England, 1700-1830’, Memoria y Civilización 3 (2000), p.171; A. Dain, ‘Assemblies and Politeness 1660-1840’ (PhD thesis, University of East Anglia, 2000), 36-7.

[8] Shropshire Record Office, Attingham Mss, 74; Staffordshire Advertiser (11 June 1796), p.4 col. b.

[9] Shropshire Record Office, Attingham Mss, 74.

[10] Huntington Library, San Marino, California, mssSTG Stowe Grenville Elections Box 1(18).

[11] Northamptonshire Archives and Heritage Service, Accounts Book of expenses at Higham Ferrers Elections in 1818, 1820 and 1822, 1818-1822, F(M) Misc Vols 799.

[12] 8 Geo. IV, c. 27.

[13] Frank O’Gorman, ‘Campaign Rituals and Ceremonies: The Social Meaning of Elections in England, 1780-1860’, Past and Present 135 (1992): 95, 104.

[14] James Collett-White, How Bedfordshire Voted, 1685-1735: The Evidence of Local Poll Books (Boydell & Brewer, 2006), I, 155.

[15] Joseph Grego, History of Parliamentary Elections and Electioneering in the Old Days (London, 1886), 247.

[16] Zoe Dyndor, ‘The Political Culture of Elections in Northampton, 1768-1868’ (PhD thesis, University of Northampton, 2010), 185.

[17] Huntington Library, San Marino, California, mssSTG Stowe Grenville Elections Box 1(5).

[18] Grego, 80.

[19] Huntington Library, San Marino, California, mssSTG Stowe Grenville Elections Box 1(5).

[20] Alexander Lock, ‘The Electoral Management of the Yorkshire Election of 1784’, Northern History 47/2 (2010), 292.

[21] Gray, 42.

[22] Gray, 44.