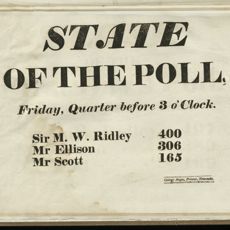

Newcastle was the commercial capital of north-east England, and even by the late seventeenth century, its politics was dominated by corporate interests, especially coal mining, manufacturing and shipping. The electorate was large, with perhaps about 5,000 potential voters by 1832, many of whom were not resident. There was a substantial Dissenting minority in the city too. But political power was concentrated in the hands of a few landed families who were closely connected with the city’s commerce. The Blacketts, for instance, held one of the borough’s seats in every Parliament from 1673 to 1777 (except in 1705–10, when the head of the family was underage), and a member of the Ridley family held a seat from 1747 to 1836.

In the first half of the century, when Whig-Tory rivalries were fierce at the national level, electoral contests were common in Newcastle. Tories routinely won both seats (except in 1722). From 1747 onwards, contests in Newcastle became much rarer, partly because party rivalries had died down, but mostly because of the expense of holding an election with such a large electorate many of whom would have to be transported to Newcastle to vote. With only a few exceptions, representation was shared equitably between one Whig and one Tory.

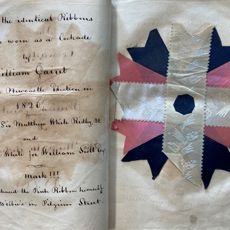

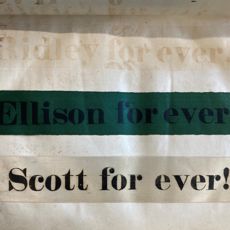

Nevertheless, Newcastle was a political city. Its factions could on occasion be mobilised, and a vibrant press kept politics in the public eye and could produce a plethora of ephemeral print when elections did take place. In 1710, the inhabitants marched around the borough in support of ‘Queen and Church’ wearing red and blue favours. In the 1770s, a national upsurge of radicalism enflamed local controversies about the enclosure of common land (the Town Moor) and of shipping on the Tyne, leading to a series of fiercely fought contests engaging many of the city’s inhabitants.

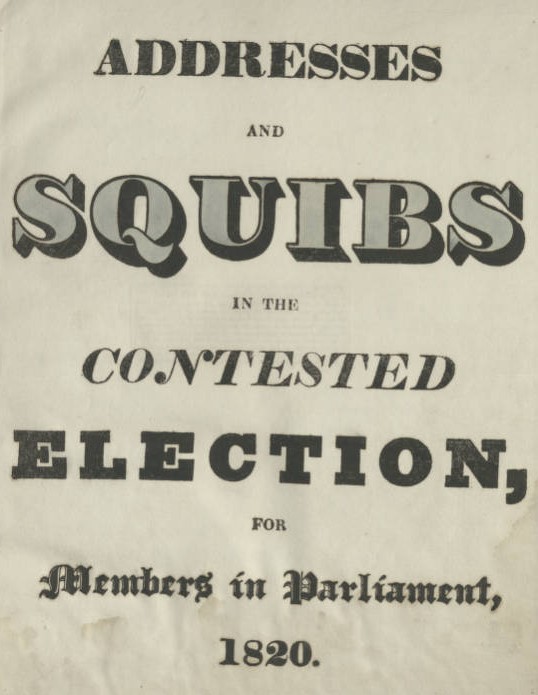

For a digitised ‘squib book’ from the 1820 Newcastle election, click on the image below.