An introduction to what happened at a typical eighteenth-century English election [15-minute read]

Elections were a key component of a continual cycle of renewing and maintaining relationships between politicians and their constituents in the eighteenth century. The years between elections provided opportunities for politicians and political families to generate goodwill with their local communities through hosting and attending dinners, fairs, and balls. Communities were both brought together and divided by elections, revolving around personalities and local issues. The process of voting in Georgian England, from the dissolution of Parliament to acclaiming the elected MPs, was laid out in minute detail to ensure the relative regularity of the proceedings in both urban and rural constituencies. While many elements of elections were carefully codified in law, much about elections was flexible and determined by local custom or the personalities of those involved. Moreover, bribery and corruption were rife throughout campaigns, despite efforts to quash these common practices.

The formal process for a General Election began with the proclamation to dissolve Parliament.[1] The Lord Chancellor sent his warrant to the Clerk of the Crown in Chancery who issued the writs of election for the county, borough and university elections; these were delivered by special messenger to the sheriffs of the counties. Within three days, the sheriff was required to send the writs or precepts to the returning officers for the boroughs, commanding them to elect their Members of Parliament, two per constituency except in a very few specific places such as London (four MPs) and Abingdon (one).[2] The date, time and place of the election was required to be proclaimed by the returning officer and held four to eight days later, but could be locally decided.[3] County elections for ‘Knights of the Shire’ were managed by the sheriffs themselves and held between ten and sixteen days later. This meant that elections took place at different times in different places. Returning officers were required to maintain public order throughout the election and secure clerks for the proper implementation of electoral procedures. Copies of the King’s proclamation were issued to bailiffs and posted around the country’s market towns.[4] The key players, generally including local elite families, would then strategise to get their favoured candidate support within the community. Since hereditary peers did not have the right to vote in an election, they were often determined to ensure their interests were represented in the House of Commons by putting forward their own nominees, often a junior member of the family or a political ally. Election committees were formed and election agents retained to drum up support for particular candidates, and might take responsibility for canvassing geographic areas or streets.[5]

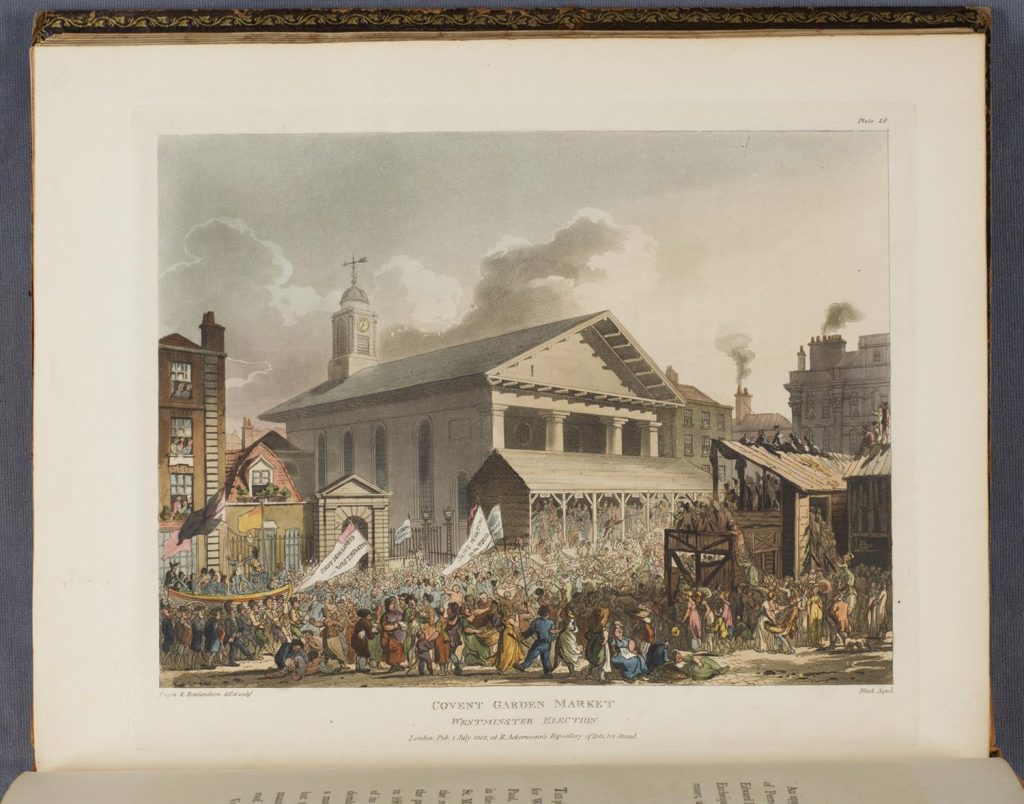

The returning officer called for a nomination meeting, in which potential candidates were proposed and seconded. A show of hands was called for to indicate early support for the candidates. In many cases, nominations were settled in advance by all parties. It might be agreed, for instance, to split the constituency between two interests (the most influential local families perhaps, or rival factions in a borough, or political parties), so that each grouping was represented by one of the constituencies’ two MPs. This avoided the need for a contested election. But if a contest was required, election committees met with the returning officer or sheriff following the nominations to discuss the regulations for the election, including construction and organisation of the polling and poll booths.[6] In the eighteenth century, there could only be up to fifteen poll booths, erected at the expense of the candidates themselves.[7]

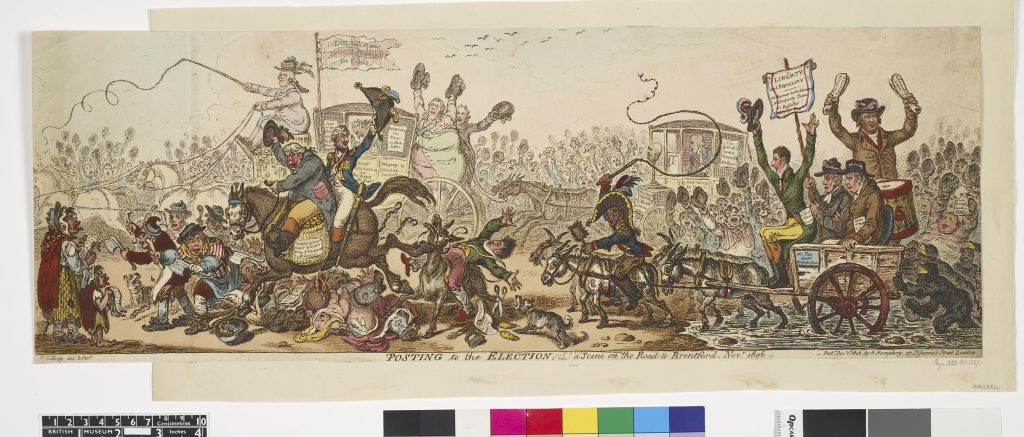

During the period between nomination and the opening of the poll, active canvassing often took place, with candidates and their agents travelling around the borough or county asking constituents for their support and promises to vote for them. Election agents collected notes on political allegiance and details on electors’ livelihoods and families. The election agent was described as ‘the person immediately known to and connected with the electors in small boroughs; he manages all their affairs; he assists them amidst all their wants and necessities’.[8] In the county election for Hampshire in 1807, thirty election agents were employed by one of the candidates, while Lord Milton’s expensive campaign for Yorkshire in the same year deployed around one hundred agents to cover the vast county.[9] In order to win over voters, candidates sometimes launched their campaigns with a dinner, as Brougham and Creevey did in Liverpool in 1812. Candidates often held dinners and balls to generate goodwill and rally supporters. Although theoretically illegal due to legislation in 1696 and 1729, bribery was commonplace. To get around the illegality of bribing voters outright, electoral ‘treats’ of food and drink were offered; fuel was distributed to those in need; the travel costs of ‘outvoters’ travelling larger distances from outside the constituency were paid or coaches specially hired to transport voters to the polls; the children of voters were sometimes treated and offered sweets; while other candidates purchased goods from voters at inflated prices, ensuring that money changed hands without violating the 1729 Bribery Act.[10] Providing transportation and accommodation helped to keep different factions apart in order to prevent violence, and the possibility of persuasion by the opposing campaign. Over the course of the nineteenth century, politicians sought to crack down on treating and bribery. In 1806, an Election Treating Bill was read, debating the practice of providing food, drink and transportation to voters. Ultimately, the bill was not passed. Bribery and treating were once more debated in 1840, ultimately affirming that voters who lost a day of work to vote ought to be compensated with food and drink.

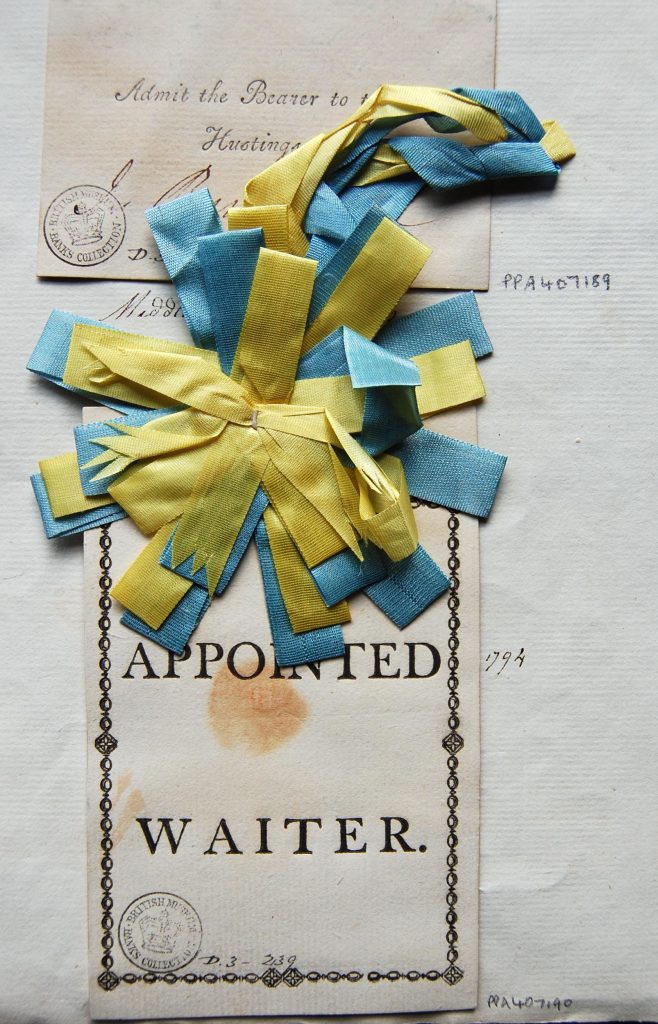

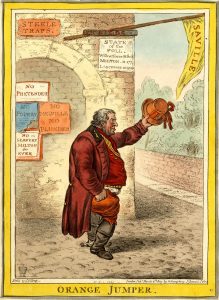

Agents and local shopkeepers might produce and distribute ribbons, cockades and other favours in the candidates’ colours. These could be publicly worn by supporters – whether eligible to vote or not – to indicate their political allegiance and perhaps persuade others to join them. During the 1784 Westminster election, Charles James Fox’s colours were blue and buff, a colour aligned with American revolutionaries in the 1770s and 1780s, while his opponent, Sir Cecil Wray, was represented by green. By 1827, an act of Parliament forbade the distribution and wearing of partisan cockades and ribbons, hoping to reduce electoral violence.[11] However, the practice of wearing a candidate’s colours was so central to popular participation that it was difficult to enforce.[12]

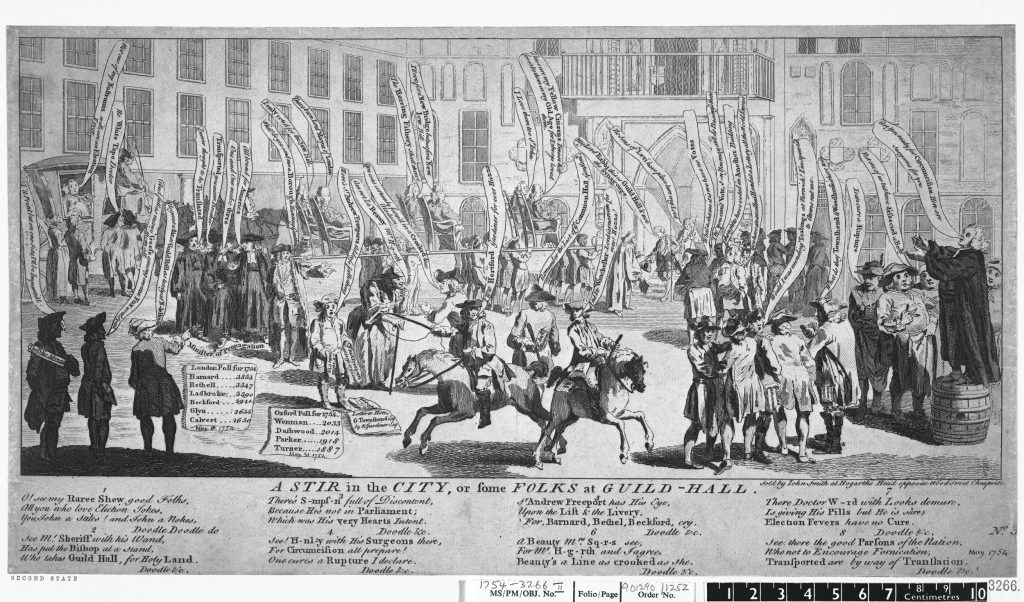

Over the course of the campaign, speeches were given on the hustings and in key public venues to outline the candidates’ platform and campaign promises. Printed handbills and squibs were often distributed to homes and on the streets, keeping the local population up-to-date on election news, campaign promises and the purported failings of their opponents. During the elections themselves, which could last several days, the latest polling data would be published. New lyrics were even written to popular tunes and might be sung at dinners, on the streets, and during processions to create support for candidates, or attack their opponents.

The opening of the polls formally started the election. The returning officer (a role usually performed by the sheriff, mayor, or local grandee) attended the hustings where the writ of election was formally read before the crowd. The returning officer swore oaths of allegiance, supremacy, and abjuration as required by law (2 Geo. II c. 24. s. 24), followed by the bribery oath to attest that officials and voters had not accepted money for their votes. The poll clerks were similarly sworn in (as according to 25 Geo. II c. 84 s. 7):

- ‘I, [Name], do solemnly swear, that I have not directly nor indirectly received any sum or sums of money, office, place, or employment, gratuity, or reward, or any bond, bill, or note, or any promise or gratuity whatsoever, either by myself or any other person, to my use, or benefit, or advantage, for making any return at the present election of members to serve in Parliament. And that I will return such person or persons as shall, to the best of my judgement appear to me to have the majority of legal votes. So help me God. [Name]’.[13]

- ‘You shall swear truly and indifferently to take the poll at this election, and to set down the name of each voter, and his addition, profession, or trade, and the place of his abode, and for whom he shall poll; and to poll no person who is not sworn or put to his affirmation, where by law any oath or affirmation is required. So help you God.’

It was still possible for new candidates to be proposed at this time, while some nominated candidates might drop out of the contest if they feared certain defeat. The candidates (either present or in absentia) were then proposed and seconded before the returning officer called for a show of hands. If the election was contested a formal poll would proceed.

Then the poll began, a process in which those entitled to vote cast their two votes (unless only one seat was being contested, as in by-elections, in which case each voter could cast a single vote). Voters could cast both votes for complimentary candidates (voting ‘straight’); divide them between two rivals (‘split’); or cast only one of their votes and discard the other (‘plumping’). Votes were given orally, meaning that those gathered around the hustings could hear who voted for whom, a situation that didn’t change until the introduction of the secret ballot in 1872. Voters came up in ‘tallies’, groups of ten to twenty men voting for the same interest, providing some collective protection from voter intimidation and rival factions itching for a fight. The tally might be headed by a tally captain who wore the candidate’s colours, leading the group, sometimes under a banner and accompanied by musicians, to the polls. Candidates could and did spread out the number of tallies they put forward, so as to extend the election over the days of the poll. Tallies from each candidate approached the polls in turn to try to prevent violence from breaking out, and disrupting the election.

The voter walked up to the polls, which were manned at the entrances by constables tasked with admitting voters.[14] The polls were manned by one deputy sheriff to examine every voter and refer any objections to voters to the sheriff’s booth (selected from attorneys not engaged as election agents for any of the candidates); one poll clerk to record the vote; one election agent per candidate to object to doubtful votes; one messenger per candidate to conduct the objected voters into court; and one cheque clerk for each candidate to confirm voter on the tax registers. In Taunton in 1830, there were groups of local men and women who acted as witnesses and accompanied the tallies to the poll. They witnessed the procedure above, but also served to provide confirmation for, or refusal of, a voter’s right to vote according to whether the voter fulfilled the conditions of the franchise in that constituency. Oaths attesting to land ownership and bribery could be administered.[15] This was not always done, but candidates could require them to be sworn if they thought bribery or improper property ownership was being claimed. Votes were recorded in poll books, alongside the voters’ names and other information such as place of abode, occupation, where the property was on which their entitlement to vote was based, and any queries or objections.

The polls were required to be open for at least seven hours each day.[16] The size of electorate varied widely between different constituencies, and a poll could be over in hours, or even minutes, while others lasted days or weeks. The Act of 1696 imposed a maximum limit on the number of days of polling at 40. However, following the 1784 Westminster election (which lasted for the full forty days until the borough was ‘polled out’), new legislation was introduced in 1785 to limit the poll to 15 days.[17] If a poll was not completed in the day, the returns were tallied by the deputy sheriffs and ‘cheque clerks’ at each adjournment of the poll, who delivered the day’s totals to the returning officer. The returning officer then proceeded to the hustings to announce the State of the Poll that day and the aggregate of the whole poll thus far.[18]

Candidates were then free to address the crowd. They spoke (by custom) in the order they fell in the polls, with the leading candidate speaking first. Usually, these speeches expressed thanks to the voters for their votes during the day, followed by astute flattery of the voters, a repeat of whatever the key message was that the candidate was using to sell himself, and some veiled (or not so veiled) criticism of the opposition. The speeches from the hustings generally ended with some sort of a casting forward to the next day’s voting and exhorting those who had not yet done so to vote. After the speeches on the hustings were over, candidates usually led the way, complete with bands of music and banners to a tavern that was their headquarters, or to an open public space, such as a square, or to the houses where they were staying. These processions usually ended with the candidate speaking again to his supporters from an elevated position such as a window or by standing in an open carriage. Processions and dinners were held to generate more support for the candidates. Sometimes violence and riots broke out between candidates’ factions, transforming the election into a rowdy and contentious civic and political event.

On the closing day of the poll, the votes were tallied and the final return was made. The returning officer proceeded to the hustings to announce the state of the poll and final result. The Indenture of Election was then read out before the crowd.[19] The losing candidate could demand a scrutiny, at which point the returning officer withheld making a return to scrutinise the credentials of the voters and reject any illegal votes.[20] If the result was challenged beyond the scrutiny, petitions had to be submitted within fourteen days of the start of the new parliament.[21] Such petitions were regularly submitted to determine the outcome of an election.[22] The 1770 Parliamentary Elections Act (10 Geo. III c. 16) was enacted to hear petitions before a Select Committee of fifteen MPs, responsible for examining witnesses to bribery or fraud and assessing challenged votes. Petitioning was a lengthy process, and its expense typically had to be borne by the defeated candidate.

If a return was made, the candidates were often then carried throughout the city by their supporters, a tradition called ‘chairing’. Crowds of men, women and children followed the procession (some cheering, some disgruntled). The chair was typically decorated with favours and ribbons in the candidate’s colours and preceded by men on horseback.[23] The procession was typically enlivened with music, flags, and the sounds of increasingly drunken cheering. At the end of the chairing, the candidates were taken back to their election headquarters where the chair would often be torn apart by the crowd.

To celebrate the victory with their supporters, dinners were usually held shortly after the close of the poll (anywhere between the close of the election and a few days later), with election balls held after that to allow the election committee to organise the event. As well as rejoicing in victory, it could be said that the intention of these events was to bring the community together again following a period of sometimes bitter division. Following an election, tokens and medals commemorating the elected candidates were sometimes distributed to supporters, and further handbills and songs might be published commemorating the events. Even after the campaigning had subsided and candidates had taken their seats at Westminster, elections lived on as a significant element of the constituency’s collective identity, woven into the socio-economic structures, cultural fabric, and personal relationships of the whole community. Once the election bustle settled down, the cycle began all over again in the years and months before the next election.

[1] Jonathan Gray, An Account of the Manner of Proceeding at the Contested Election for Yorkshire in 1807 (York, 1818), 1.

[2] As well as London, the united boroughs of Weymouth and Melcombe Regis returned four MPs, while five boroughs returned just one Member each: Abingdon, Banbury, Bewdley, Higham Ferrers, and Monmouth.

[3] Gray, 2.

[4] Gray, 3.

[5] F. O’Gorman, Voters, Patrons, and Parties: the unreformed electoral system of Hanoverian England 1734-1832 (Oxford, 1989), 83.

[6] Gray, 6.

[7] Gray, 7; 18 Geo. II c. 10, s. 7.

[8] 19 May 1809, Parliamentary Debates, xiv, 666; O’Gorman, 87.

[9] O’Gorman, 83-4.

[10] O’Gorman, 160-3.

[11] 8 Geo. IV, c. 27.

[12] Frank O’Gorman, ‘Campaign Rituals and Ceremonies: The Social Meaning of Elections in England, 1780-1860’, Past and Present 135 (1992): 95, 104.

[13] Gray, 22.

[14] Gray, 25.

[15] 2 Geo. II. c. 24.

[16] Gray, 18.

[17] O’Gorman, 135.

[18] Gray, 28.

[19] Gray, 38.

[20] O’Gorman, 164.

[21] O’Gorman, 164.

[22] J.H. Plumb, The Growth of Political Stability in England 1675-1725 (London, 1967) , 86.

[23] O’Gorman, 138.