Robin Eagles asks why certain elections were contested, while others were not [20-minute read]

In May 1741 the Nottinghamshire gentlewoman Gertrude Savile (sister of Sir George Savile, bt. MP for Yorkshire), commented with relief on the conclusion of the recent elections. She reported:

Great struggles and mob[b]ing in several places espeshily [sic] Westminster, yet thank God, not prov’d so bad as I expected, I dreding it being the beginning of a Civill War.[1]

Savile’s experience reflected both the tensions inherent at election time, but also the uncertainty. Some constituencies almost never went to the polls, while others were open to challenge. In some cases, this was because of ingrained interests. In others, like Westminster which Savile referred to, it was because such large electorates were difficult to control or predict. Thus, while Nottinghamshire had been settled (as was usually the case) without going to a poll, there had been contests at the Nottinghamshire boroughs of East Retford and Newark. In the former, where one seat was usually up for grabs, William Mellish had challenged both Whig sitting MPs, pushing one of them into third place. To ensure his success he had spent royally, scattering his money at a rate of anything between £50 and £150 a vote.

Eighteenth-century elections were often lively affairs but as Savile shows, for some there was a real element of danger that accompanied the meetings, riots and general high spirits that accompanied them. It was not just in places where elections resulted in a formal poll where hullabaloos might arise; even constituencies used to settling affairs without troubling the voters to turn out might experience energetic meetings with potential candidates wooing their supporters. So an uncontested poll by no means meant an uncontested election.

Of course, one needs to be aware that there is a distinction between county seats and borough seats – and within those, different types of borough. Between 1715 and 1754 numerous county seats experienced contested elections, but this altered for the second half of the period when only Hertfordshire (4) and Westmorland (3) experienced more than one or two contests. Interestingly, Hertfordshire, which was an especially hard-fought county, had also seen four contests in the period 1715-1734. Devonshire saw no contests in the period 1715-90 and Wiltshire experienced only one, a by-election. Oxfordshire, similarly, saw only one, but that particular example (1754) was notorious for its ferocity. [2] Middlesex achieved especial notoriety thanks to the radical politician John Wilkes, who had returned from exile to stand for Parliament and secured election in spite of being an outlaw, inspiring a wider movement as a result. The county experienced no poll in 1774 or 1780, but there was a lively contest in 1784 when Wilkes was pressured into second place after a challenge.

Wilkite agitation of the 1760s and 1770s made an impact in a number of places beyond the bounds of London and Middlesex. It was noticeable that Essex, otherwise a fairly predictable county, experienced contests in 1768 and 1774, though in this case the challenge seems to have come more from the ‘old interest’ rather than Wilkites and the government candidates still prevailed. Maldon (one of the boroughs within Essex) was, however, one of the first constituencies to experience pressure exerted by Wilkes and his followers around the time of the North Briton affair. When the sitting MP Bamber Gascoyne was forced to fight a by-election in April 1763 he was in no doubt that the opposition he faced had been ‘founded by that ingenious gentleman Mr Wilkes and his crew’. At the resulting poll on 26 April, just a few days after the publication of the famous Number 45 of the North Briton, Gascoyne accordingly was defeated by John Huske, who had secured the corporation’s backing. Gascoyne conceived that Wilkes and his supporters had been inspired by Thomas Tracy’s successful challenge in Gloucestershire around the same time, after Norborne Berkeley vacated his seat to go to the Lords. His belief that the Wilkites tended to approach such contests in an opportunistic fashion appears to have been broadly correct.[3]

The picture was much more varied in the boroughs, not least because of the different franchises in play. One borough seat that never avoided a poll at general elections was Canterbury. The franchise there was in the freemen and with between 1,300 and 1,500 voters it was sufficiently populous and free of one overarching individual or corporate body exerting interest for it to be a lively and dynamic constituency.[4] This was certainly reflected in the fortunes of its candidates. Thomas Best, who was elected in 1741 retained his seat in 1747, lost it in 1754, regained it in 1761 only to lose it again in 1768.[5] It was a place where local connexions seemed to be of especial importance, with the majority of the MPs being at least local to Kent and the voters highly suspicious of ‘foreigners’ (i.e. people from outside of the county).

Unlike Canterbury, Aldborough and Camelford saw no contests. East Grinstead in Sussex was also usually spared the trouble of going to the polls. As a burgage borough, East Grinstead was subject to the patron in command of the majority of burgages and as the duke of Dorset owned most of them as lord of the manor, he was rarely challenged there. The reason for Camelford normally being spared the expense of a poll was different. There, the franchise was in the freemen paying ‘scot and lot’, and there was more than one potential patron. Even so, contests were avoided despite occasional threats from new interests acquiring influence there.

What does need to be borne in mind, though, is that avoiding a poll by no means meant that a borough missed out on a lively electoral culture, or that fierce contests and negotiations went on behind the scenes. Aylesbury reveals perhaps as well as any the fundamental difference in play between an uncontested election and an uncontested poll. Unlike Canterbury, Aylesbury was a borough where anyone willing to spend freely might stand a reasonable chance of carrying the place. The History of Parliament entry on the place notes it as ‘squalid and venal’ and the experience of its various MPs in the eighteenth century certainly bears this out. John Wilkes established himself as lord of the manor following his marriage to Mary Mead (owner of Prebendal House) in 1747 but it took him until 1757 to find an opportunity of securing the seat for himself. In the intervening period he gave his backing to Thomas Potter – who faced a challenge at the 1756 by-election from an obscure challenger named Frederick Halsey. Halsey successfully defeated Potter at a poll in December, but the result was reversed on petition as it was found that there were a substantial number of unqualified voters on Halsey’s list.[6] Aylesbury was a borough where treating was de rigueur. It was Potter’s understanding of this that had led him to try to suppress knowledge of his appointment to office for as long as he could (as this would trigger the by-election), as he confessed he only had £500 available to spend.[7]

Wilkes’s experience also points to the careful cultivation of a borough required by many candidates, though he seems to have been particularly adept at planning and list-making. Prior to his election in 1757 he had angled for an entrée as Potter’s partner in 1754, but had to hold back as another candidate, John Willes, was unwilling to give way. Once Potter had indicated that he wished to find an alternative seat, Wilkes worked hard to cultivate the people he hoped would soon be his constituents. This included detailed discussion of levels of treating with his agent, John Dell, but he was also indebted to Potter for careful guidance on when and how the election writ ought to be delivered to minimize the chances of a challenge.[8]

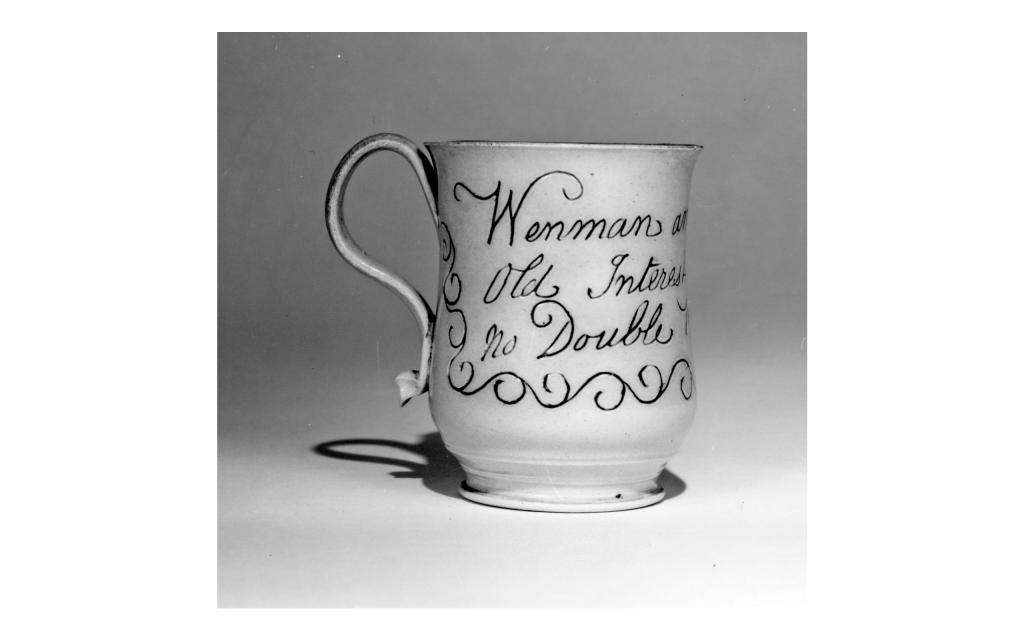

In some cases, of course, no amount of careful negotiation could prevent a poll being called for. The fiercely fought Oxfordshire election of 1754 was as much about national as local circumstances. Here, while previously the Tories had been able to hold sway over the county seats, and subsequently a deal was arranged whereby representation was shared by one Whig and one Tory, the ‘new Whig’ interest proved determined to challenge the incumbent Tories. Just how chaotic the poll was, was reflected in the fact that all four candidates: Viscount Wenman and Sir James Dashwood for the Tories and Viscount Parker and Sir Edward Turner for the Whigs, were returned. (This was somewhat unfortunate, given that one example of election-ware produced around the time declared the maker’s support for Wenman and Dashwood, proclaiming ‘Old Interest for Ever no Double Return’.) It was not until April 1755 – a full year after the poll – that Parker and Turner were confirmed in their seats, even though both had polled fewer votes than their rivals. (See feature on Controverted Elections.) What was particularly interesting here, was that neither side cared to repeat the experience and that for the remainder of the period the county seats were shared with one Whig and one Tory each holding one.

Above all, contested elections often pointed to significant changing features in the broader national political system. During the 1740s when there was an active campaigning Prince of Wales, a degree of urgency was injected into certain seats that might previously have been thought safe government strongholds. An alteration in the status of a dominant family also had obvious, knock-on effects. Few grandees had such a wide and dominating interest in a number of places than Thomas Pelham-Holles, duke of Newcastle. When he died, the vast majority of his interest passed to the earl of Lincoln (who also succeeded as 2nd duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne) but Lincoln’s expected succession had already introduced tensions into some of the boroughs as he began to angle for position before inheriting.

Even in places where notable borough-mongers were thought likely to hold sway without much difficulty, challenges were possible. Between them, the dukes of Newcastle and Richmond held a tight grip over much of Sussex, but other interests were not unknown there. In June 1747 Richmond reported to Newcastle that expected opposition in the county was ‘as trifling as that at Lewes’. He could not be so certain of prevailing in Arundel, though, close to his Goodwood estate.[9] He was correct. The borough had previously been dominated by the Lumley earls of Scarbrough, but the place was difficult to control and in 1747 the 3rd earl of Scarbrough (himself a former MP for Arundel) failed to nominate candidates. Richmond attempted to fill the void by nominating two of his own, but was outpolled by sitting MP Garton Orme, joined by Theobald Taaffe, who had been developing his own interest in the borough close to his Midhurst estates. Arundel’s experience pointed to the opportunities available when an established interest withdrew even where an apparently influential grandee, like Richmond, was on hand.

In 1727, Bedfordshire had experienced the problems caused by a new local power-broker – in this case the underage duke of Bedford – attempting to impose candidates against the general feeling of the county. The year before, Bedford had summoned a county meeting but in such a way that at least two of the county’s grandees refused to attend. Bedford then hit upon setting up two men, while ignoring efforts to secure a compromise arrangement. Two months before the poll, Bedford’s preferred candidates, Sir Humphrey Monoux (‘theoretically a Jacobite’)[10] and Sir John Chester, set about seeking support from the neighbouring gentlemen, assuring their correspondents that Bedford and ‘several (we presume the majority) of the principal gentlemen’ were keen for them to stand.[11] Such efforts made no difference at the eventual poll, which saw both men rejected. The seats went instead to one of the sitting candidates (Sir Rowland Alston) and Pattee Byng, heir to the viscountcy of Torrington.

What all of these examples indicate, is that electoral culture throughout the eighteenth century was lively and varied. While some seats rarely saw contests, the potential for competition was always there. This might be because of the failure of an established patron to nominate acceptable candidates (as in the case of Scarbrough in Arundel), or because a new force had not yet gauged correctly the general sense of the area (like Bedford). As Thomas Potter and John Wilkes found, venal and corrupt boroughs were no guard against challenge and both men worked hard to keep their constituents satisfied, providing treats as well as handing out hard cash. That it was an at times exhausting and dispiriting experience was suggested by Wilkes in unusually unguarded mood, complaining in the aftermath of his 1761 re-election: ‘I will not be the dupe of the mob, nor a few wretched impertinents’.[12] It was a sentiment that was no doubt shared by any number of his fellow candidates throughout the period.

[1] Secret Comment: the Diaries of Gertrude Savile 1721-1757, ed. Alan Saville (Thoroton Soc. 1997), 244.

[2] The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1715-1754, ed. Romney Sedgwick (1970), i. 116; Commons 1754-1790, ed. Sir Lewis Namier and John Brooke (1964), i. 514.

[3] The Jenkinson Papers 1760-1766, ed. N.S. Jucker (1949), 147.

[4] Frank O’Gorman, Voters, Patrons, and Parties: the unreformed electoral system of Hanoverian England 1734-1832 (Oxford, 1989), 58.

[5] History of Parliament: the Commons 1715-1754, i. 460.

[6] History of Parliament: the Commons 1754-1790, i. 214-15.

[7] BL, Add. MS 30867, f. 125.

[8] John Wilkes: the Aylesbury Years (1747-1763) His Collected Letters to his Agent, John Dell, ed. Alan Dell (Buckinghamshire Papers, xvii, 2008), 18-20.

[9] The Correspondence of The Dukes of Richmond and Newcastle 1724-1750, ed. Timothy J. McCann (Sussex Rec. Soc. lxxiii, 1984), 248.

[10] How Bedfordshire Voted, 1735-1784, ed. James Collett-White, (Beds. Hist. Rec. Soc., xc, 2012), 2.

[11] BL, Add. MS 61684, ff. 146-7.

[12] Wilkes: the Aylesbury Years, 34.