The canvass aimed to get the vote out, but also linked candidates to communities [25-minute read]

Canvassing was, according to David Eastwood, ‘the critical electoral institution of later-Hanoverian England’, or, as Frank O’Gorman has argued, the ‘critical point of contact’ between the electoral system and the voters prior to Reform.[1] Canvasses were organized by local election committees and carried out by committee members, election agents and sub-agents (the latter often referred to as ‘captains’), and, usually at least once in every campaign, by the candidates themselves. While canvassing generally began with news of a dissolution, particularly keen candidates, or election committees in electoral hotspots, might begin canvassing well in advance of a general election. Canvassing in Oxfordshire, for instance, was under way by 1753, although the election itself did not take place until spring 1754.

An anticipated dissolution, or rumours of an impending dissolution, could also instigate a canvass, as candidates sought to wrong-foot their opponents. Thus, dowager Lady Spencer informed her son, George, 2nd Lord Spencer, on 23 December 1783 that Lord Grimston was already canvassing St Albans. Grimston’s eagerness reflected the general Whig assumption that William Pitt the Younger’s new government, formed only four days earlier, would be a ‘mince pie administration’ and would not last longer than the holiday season.[2] While Pitt proved Grimston wrong and parliament was not dissolved until 25 March 1784, news of the forthcoming dissolution, when it came, still caught twenty-five year-old Lord Spencer off-balance. Having only succeeded his father at the end of October 1783, this was Spencer’s first election in charge of the Spencer family interest and he worked closely with his mother, who was an experienced campaigner. On 20 March, having received word that the dissolution would take place within ‘three days at the furthest’, and that ‘whole county of Northampton is thrown into a violent confusion and bustle by Sir James Langham’s having declared himself a candidate for it in Case of a dissolution’, he sent a hurried letter to his mother.[3] He had, he recounted to her, already sent to London to secure the writ for Northamptonshire. Possession of the writ would allow him to set the date for the election and allow him ‘to get the Election for the town of Northampton over as soon as possible’. In order to do this successfully, he needed a Spencer family presence in the borough to carry out an immediate canvass. As he was unsure whether the family’s candidate for re-election — Lord Lucan, Spencer’s father-in-law — would be able to reach Northampton in time to do this, he asked his mother to forward a letter to her brother instead. If need be, his uncle could carry out the canvass in Lucan’s name:

I send in the next place a letter to my Uncle Poyntz which you will be so good as to direct where it is to be forwarded to him to desire him if possible to come down and to desire him if possible to come down and stay with us during this alarm, that I may have him ready to personate Lord Lucan at Northampton in his canvass, if the Parlt: shd be dissolved & he not returned in time.

Canvassing played a crucial part in contested elections: it was the only tool that pre-Reform politicians had at their command that allowed them to survey the level of support for a prospective (or returning) candidate and determine whether a contest was feasible. Many potential campaigns consequently went no further than the initial canvass. For those that did, canvasses were the primary means of recruiting voters. In the case of Northampton in 1784, Lord Lucan failed in his attempt to secure re-election. His unpopularity in the borough and his unwillingness to stand down in favour of another candidate when asked, much to Spencer’s chagrin, led to the emergence of another candidate who secured votes by campaigning against Lucan.[4]

Lucan’s failure serves as a reminder that voters in Georgian elections had varying degrees of agency and that contested elections, especially in small towns and rural areas, were superimposed upon, and had their outcomes shaped by, complex spiderwebs of local circumstances and personal relationships. Community traditions, degrees of patron control and the importance of political issues or ideological commitments all contributed to determining voter participation and choice in Georgian elections. Campaign correspondences, as well as testimonies of witnesses in controverted elections, reveal that voters’ responses to canvassing, and their decisions to vote (or not) for particular candidates, could also be determined by pre-existing relationships with the candidate or canvasser, or by personal histories of favours, obligations, debts and animosities.[5] Lady Susan Keck, canvassing one of her husband’s tenants nearly six months before the 1754 Oxfordshire election complained that the man’s promises to her mattered little given his wife’s opposition:

… whilst he was with me I cou’d do with him what I pleased, but that availeth little Since as … he is married to Another woman, he will again fall in to her claws and then my power drops. I try’d to have stroak’d her, but she is a Viper, and told me she always was of the high party — at the same time I have his Word of Honour to do everything I shall command him, but I may not meet with him this twelvemonth, and Letters will be read and Answered by his wife, in this case what signifies honour and assurance’s (sic).[6]

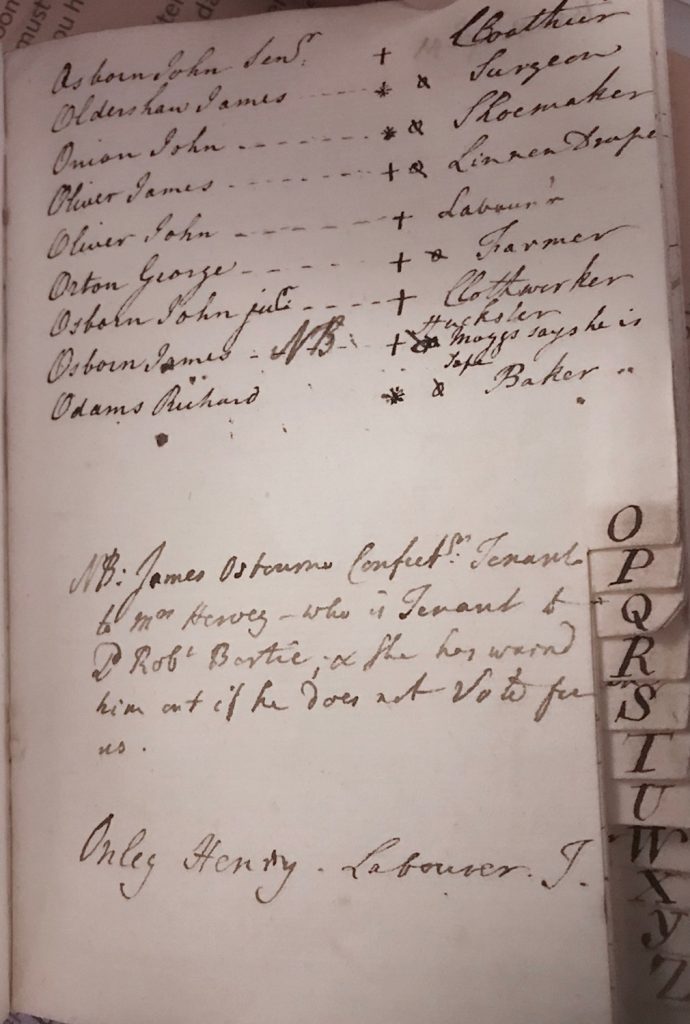

In this she was not alone. While eighteenth-century women did not vote, canvassing books and electioneering correspondences frequently provide a record of their involvement and influence. George, Viscount Townshend’s pithy annotations in the pollbook that he was using as a canvassing book in the lead-up to the 1765 Tamworth by-election serve as a case in point: although the carpenter, Thomas Healey, had promised to be neuter, Townshend noted, ‘Wife governs, against us’; similarly, the mason, John Hunter, had ‘wish’d us well, but his Wife govern’d’. Mrs Hervey, however, had given her tenant, the confectioner, James Osborn, an ultimatum: ‘she has warnd him out if he does not Vote for us.’[7]

Clement Tudway’s London election agent, W. Taverner, also believed that it was vitally important for canvassers to gain women’s support. ‘I am allwaise safe if I can get ye woman’, he wrote to Tudway as he recounted his progress in canvasssing during the fierce contest for Wells in 1765.[8] The personal dimension of canvassing (of which more below) added an additional layer of complexity to an electioneering ritual that was usually marked by some degree of social inversion. Canvasses saw ordinary power relations between canvassers and voters turned upside-down, as social superiors became supplicants, and voters or their family members — at least in theory and, in numerous instances, in practice — made their support conditional upon the canvasser being able to fulfil specific personal demands. Taverner encountered this when trying to secure the vote of a Mr Nix. He complained to Tudway that the opposing candidate for Wells, Peter Taylor, and his agents had already canvassed Nix by letter. Before Nix would agree to pledge his vote, however, he wanted to have his debts paid:

Taylor works like a mole he and his Emisares (sic) Endeavours to find out all ye Conection wth the Voters Mr Nix has had Severall letters wth great promises if he will be of their Side his depts [debts] shall be paid directly & the recipts send up to him I have been to him this day to Hamersmith and his wife & him are very Uneasy because of Creditors knows where he is so yt he is afraid to stir out begs to know if any thing is done for him you may depend on his vote…[9]

Three weeks later, Taverner was still trying to secure Nix’s vote. Fine words and vague promises from Clement Tudway had not been enough to persuade Mrs Nix. Although the vote was her husband’s, Taverner recognised that the final decision would be hers:

Mrs Nix do Insist ye Bond due to Moss be paid off directly and then she will tell Burling & all of ’em of yt party not to trouble her Husband for yt his vote will be agt them She is very uneasy yt it is not done allready I read yr letter to her but it did not Satisfie her he shll not Stir an Inch She says before it is done nither can she Sleep as they know where he is….[10]

Public Canvasses

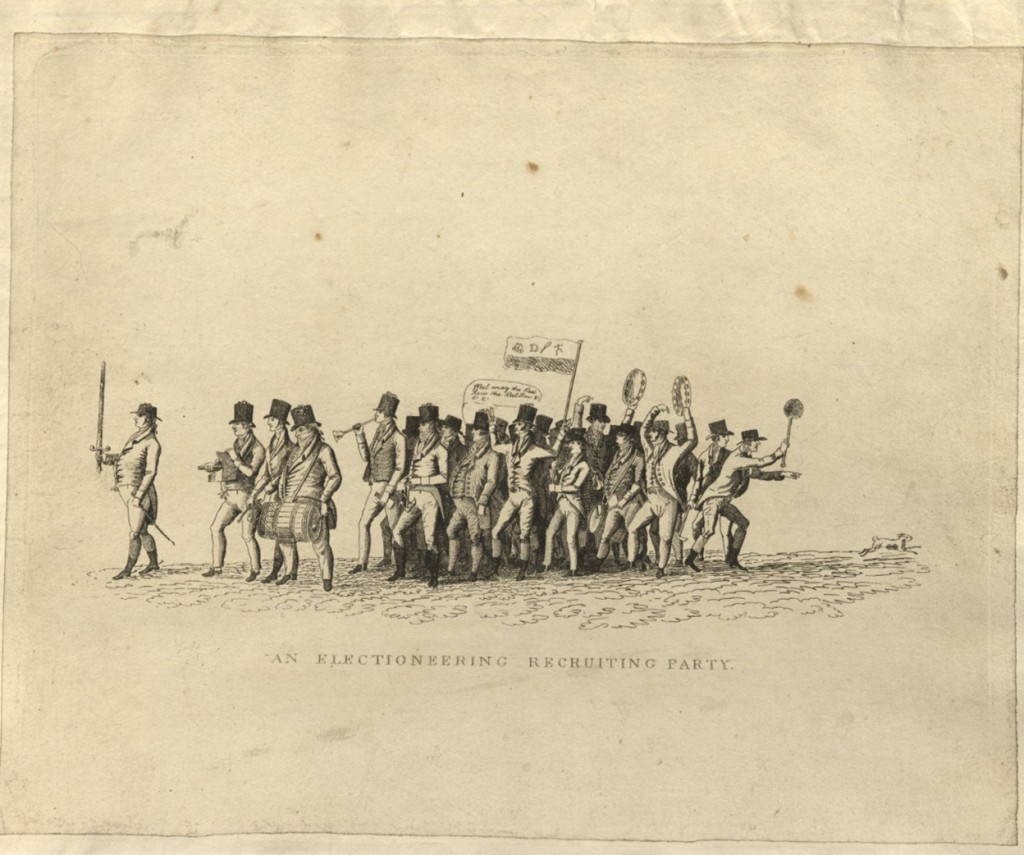

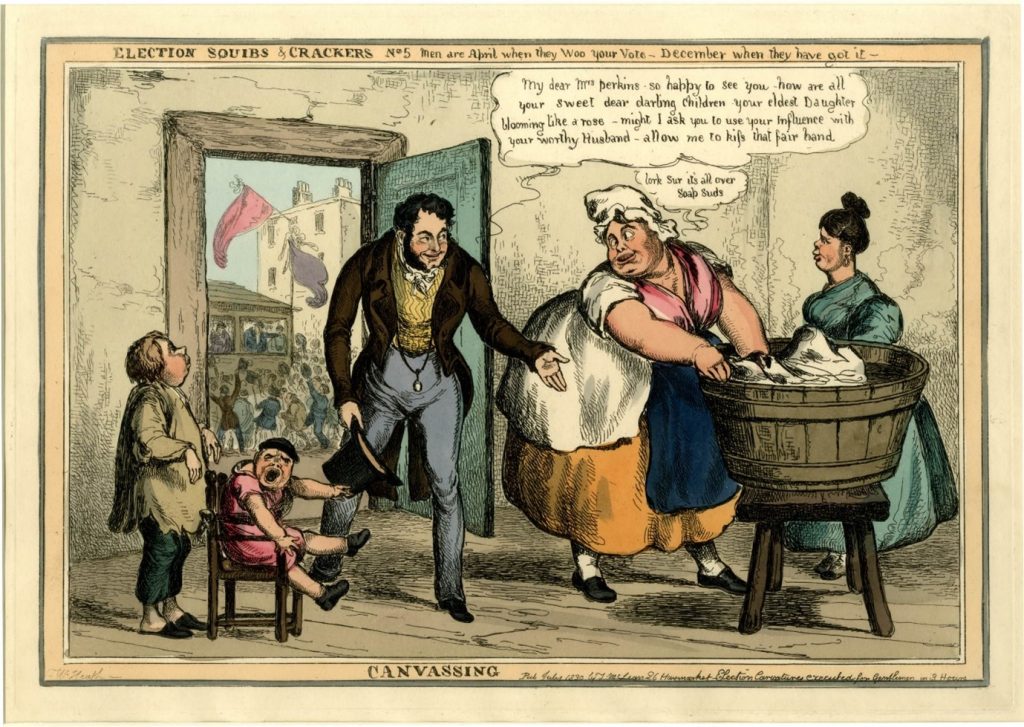

As these examples suggest, canvassing was not always quick or straightforward. Elections generally saw two sorts of canvass, which can be roughly categorised as public and private. Public canvasses were often colourful and impressive pieces of political street theatre, designed to create a spectacle, attract crowds of voters and non-voters on to the streets, and generate excitement. They ideally took place at the beginning of a contest in order to introduce the candidates to the voters, mop up the easy votes, and determine whether there was enough support to continue to a poll. The canvassing party — usually an imposing group in itself, comprised of the candidate, his close friends and/or (generally male) family members, and a smattering of important patrons and elite supporters — would enter the town, smartly dressed, often in party colours, bedecked with ribbons and cockades. They would be met on the outskirts of the town by as large and impressive a group of supporters as the committee could muster. At the very least there would local dignitaries on horseback and assortment of hired stavesmen, flagbearers and musicians. Children, especially young girls dressed in white, were also often members of the ensuing procession. With the band playing, flags flying, banners aloft, and the canvassing group and many of the supporters bedecked with cockades and ribbons in the candidate’s colours, the procession would make its way through the town to a central public location, such as a market square where a crowd could gather.

These entries and processions were often reported in glowing terms by local newspapers. The Dorset County Chronicle, for instance, clearly relished the colour and excitement of the Tory candidate, General Peachy’s, entry into Taunton at the end of August 1830:

Tuesday, the 24th of August, proved a day of considerable importance and gratification to the Blue party of Taunton; early in the morning the bells rang merrily, and persons were seen busy in decorating themselves and families in the favourite azure emblem; the managing supporters of General Peachy had considered it more prudent to avoid a public procession, but the importunities of his friends were so urgent, that the objection was cheerfully removed, and in a few hours the Blue Banners that were then decorating the walls of the banquet room at the Castle, were transferred to the pole. At two o’clock the procession was formed at the Eastern Turnpike, from whence it conducted the General through the principal streets of the town; the number of blue banners with the variety of devices, and each person of the numerous assemblage wearing a “bunch of blue ribbons” exhibited an appearance highly interesting. The General was warmly greeted from the windows as he passed, and from the hearty flourish of his proud colour from “fairer hands,” it was certain that the “more delightful portion of the creation” were among his strenuous supporters.[11]

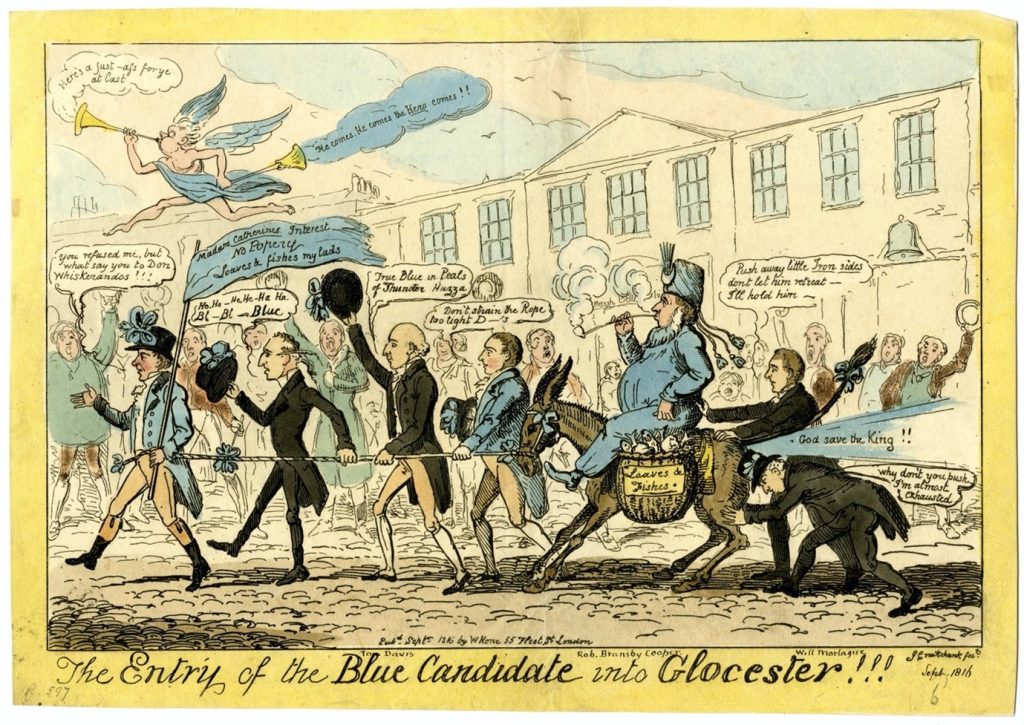

Of course not all the reporting was this flattering. The rituals of elections and the glorious idiosyncrasies of candidates and campaigns provided both amateur and professional artists with no shortage of material for graphic satire. Election prints that sent up candidates, canvassers and voters, such as George Cruikshank’s mockery of the Blue candidate’s entry into Gloucester in 1816, contributed to the barrage of printed material that elections generated.

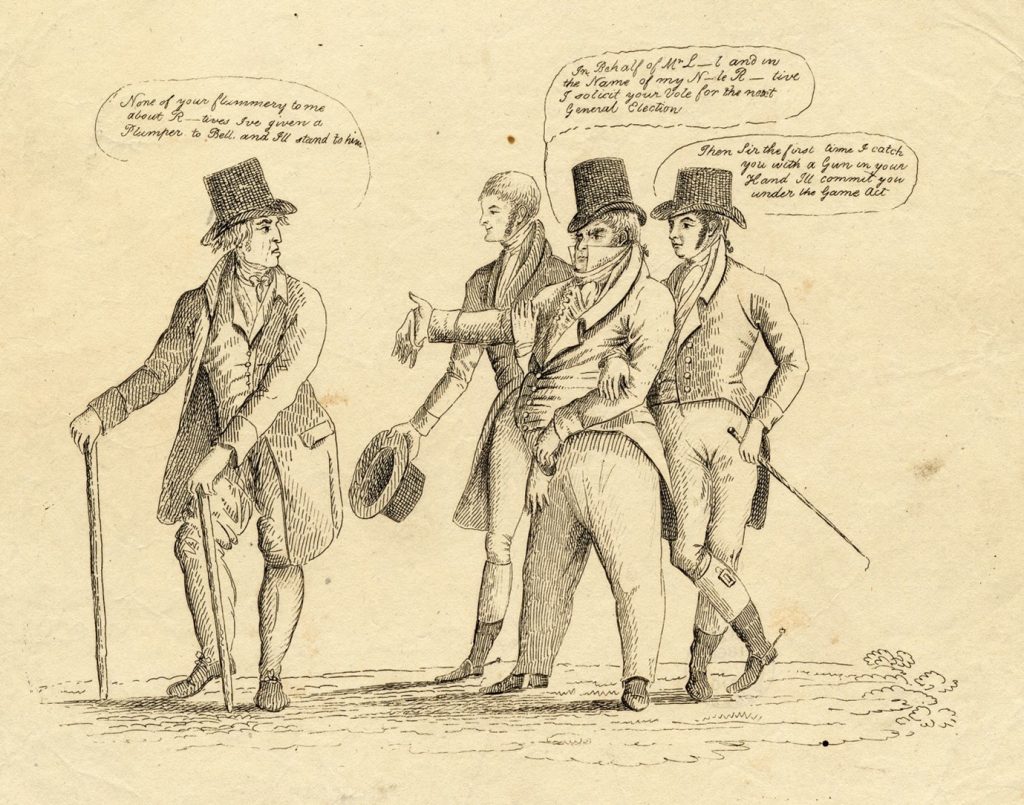

After gathering at a central public location in the town, the canvassing group would be formally introduced; key supporters would give (hopefully) rousing speeches and the candidate would address the crowd and ask for voters’ support. The canvassing group would then process through the town, calling on voters as they went in a grand show of polite condescension, and securing votes. The size and quality of the candidate’s group of supporters spoke to his commitment to the town and — as with his willingness to treat liberally — to his future generosity and service to its voters. In Taunton, by the 1820s, candidates were accompanied about the town by bands of musicians and a minimum of thirty-two local men carrying the various ‘Stand[s] of Colours’ from the town’s sixteen Friendly Societies. All were paid for their efforts, but the clubmen’s service was put to a collective as well as a personal good. They paid their wages to their club Stewards, who returned each man half a crown per day’s employment; the remaining money went in to the Society’s coffers to cover members’ illness and burial costs.[12] The canvassing party depicted for the Northumberland election of 1826 was significantly less ostentatious and would, presumably, have cost the candidate significantly less money.

Canvassing the Ladies

Public canvasses tended to be full-day affairs. They might start as early as 8 a.m. and go on until 9.00 or 9.30 p.m., any day of the week but Sunday.[13] For voters who worked away from home, this could mean that the canvassers spoke not to them, but to their family members, often their mothers, wives and daughters. As both committee members and gentlemen canvassers assumed that taking ‘liberties’ with good-looking women of the electorate was one of the fringe benefits of canvassing — the most common of which may have been the customary election kiss — some canvassers appear to have timed their canvassing to coincide with men being away from home.[14] Edward Walker, who had canvassed for three days with the (ultimately successful) pro-Reform Whig candidate, Edward Bainbridge, in Taunton in 1830, was asked specifically about this when testifying to the select committee ruling on the controverted election. When questioned about Bainbridge’s unsuccessful canvassing of Ann Tames, ‘a very nice looking woman’, his answers reflected the contemporary presumption that voters’ womenfolk welcomed canvassers’ advances:[15]

Your attention perhaps, was drawn to the females there.

I would certainly rather canvass the ladies, than the gentlemen.

Were you going into any other house, were there were any females?

There were females in most of them; the ladies in Taunton rather made a point of being in during the canvass.[16]

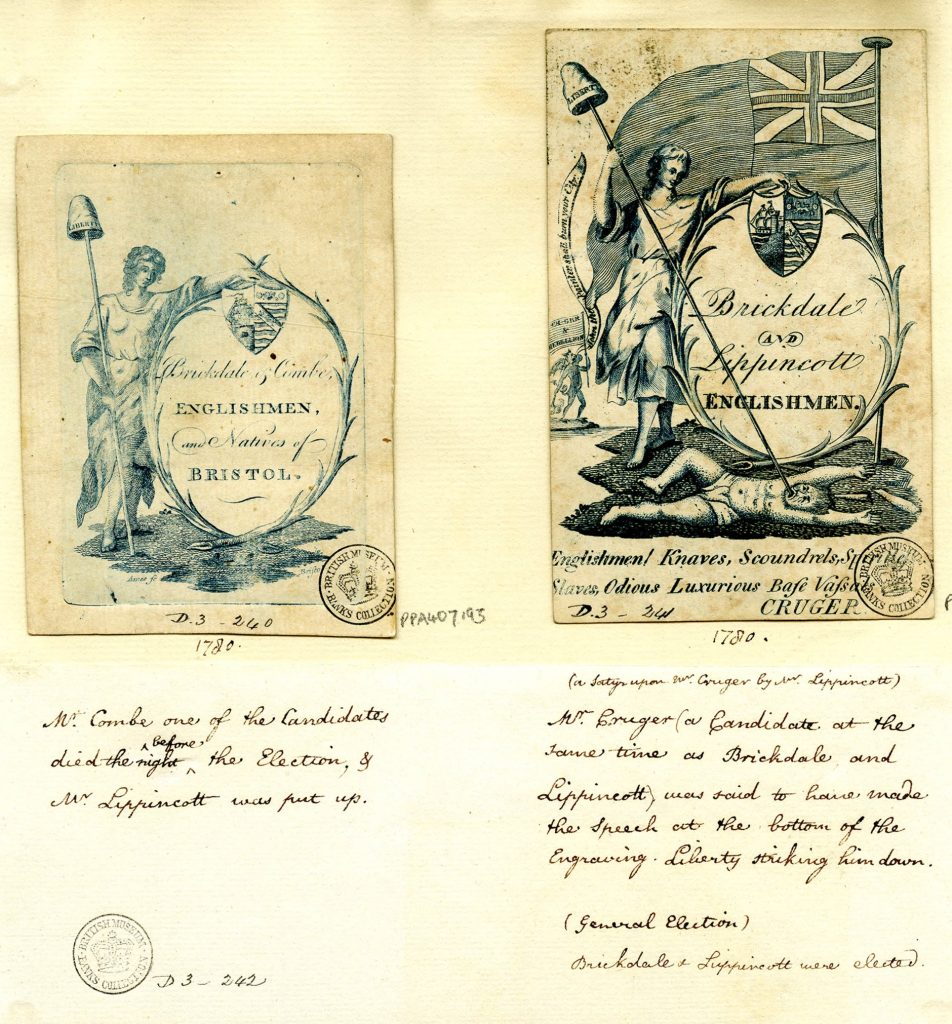

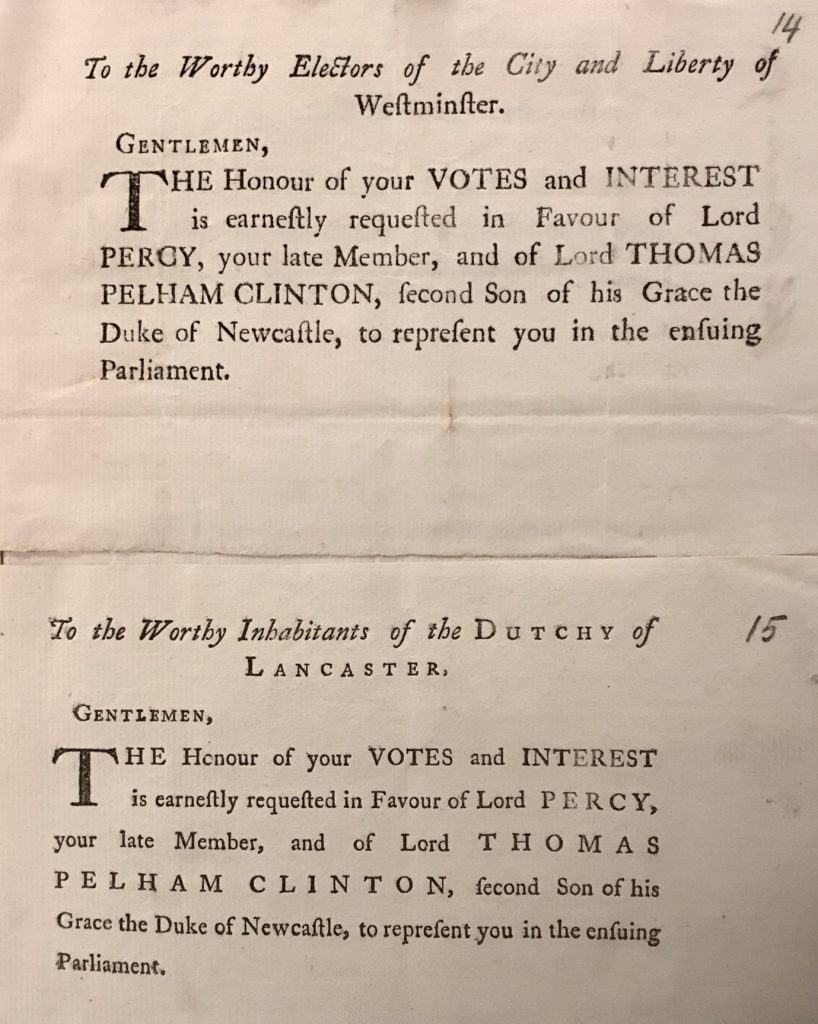

Canvassing Cards

While canvassers expected that family members would exert their influence over absent voters, they might also leave canvassing cards. These gave the name(s) of the candidate or candidates (if they were running in tandem), and might include a party slogan and a direct request for votes. Some were exquisitely polite and beautifully illustrated, whereas others were simple, practical printed requests.

Private Canvasses

Private canvasses were more varied, both in terms of approach and locations, than public canvasses. The simplest were straightforward requests for votes, made face-to-face or by letter. Aristocratic canvassers were characteristically careful in how they brought both class and character to bear when canvassing other, less socially elevated members of the political elite. Requests for votes between gentlemen, or from elite women with influence, were common. The duke of Dorset’s canvass of Sir Robert Smyth, Bt, reflects the prized gentlemanly independence of the baronet, while simultaneously invoking the social weight of his own status and that of the duchess of Grafton:

The Duchess of Grafton has desired me to apply to you for your vote and interest for Lord Euston, if you have not already engaged yourself to any other candidate for the University of Cambridge—I hope you will support him, I assure you he is a charming young man.[17]

Female Canvassers

Aristocratic women who canvassed (and there were regularly some) needed to be self-confident and resilient if they canvassed in person, particularly for candidates who were not family members. Lady Susan Keck, who was in her mid-forties at the time of the Oxfordshire election of 1754, was satirized repeatedly for her age, her grey hair and her approach to canvassing:

Let younger Wenches coax Freeholders,

And Shake their Hands, and slap their Shoulders,

And ride about, and scold, and quarrel[18]

She was advised her to take off her riding boots and attend to her housekeeping: ‘Go home and put your shoes on’:[19]

Dear Sukey moderate your Zeal

Give Room for cool Reflection

Think how such Exercise will peel

Your Bum and your Complexion.[20]

Lady Susan famously gave as good as she got, however; she not only kept canvassing but also published poems in turn that satirized the Old Interest candidates.

Young and attractive aristocratic women were feared as canvassers, as it was commonly assumed that their class and beauty combined to create a sexual allure that would be irresistable to labouring-sort men. In 1767, twenty-two-year-old Lady Susan Bunbury reputedly secured 94 out of 100 votes for her husband at Morpeth, leaving Sir William Musgrave to wonder how the remaining six voters could have refused ‘so charming a solicitress’.[21] Lady Kath Murray, who was an acknowledged beauty (though somewhat older than Lady Sarah), alluded to this belief lightheartedly in 1768. As Lady Rockingham informed the duke of Portland, Lady Kath, who was sitting beside her, ‘promises to make a strong attack upon the Affections of the Bricklayer, & to win them if possible. She … expects, that she shall see him next Week, & knows that his Vote was not engag’d when She came to town …’.[22]

The best-known example of the sexualisation of women’s canvassing in the eighteenth century is the Pittite press attempt to force the duchess of Devonshire to stop canvassing for Charles James Fox during the 1784 Westminster election. By depicting her as a common streetwalker, a drunk, or a female pugilist, and liberally inscribing prints of her canvassing with sexual imagery (including famously representing her kissing butchers for votes), the Pittites attacked her character and sought to drive her from the campaign. It nearly worked.[23] The duchess and her sister Lady Duncannon fled to their mother’s at St Albans and only returned to London and the campaign when effectively ordered to do so by the duke and duchess of Portland. It is worth noting, however, that they canvassed St Albans for the Spencer family interest while there, and that their canvassing raised none of the same issues. Not only did they succssfully out-recruit Lady Salisbury, who had also temporarily left off canvassing in Westminster to canvass for her brother in St Albans, but they also won their mother’s praise. The dowager Lady Spencer was characteristically inconsistent about electioneering: accustomed as she was to campaigning and clearly relishing working daily with election committees, she loudly lamented her daughters’ canvassing in Westminster, but bragged to her friend Mrs Howe about their success at St Albans: ‘I really believe G: & H in great measure turn’d the Election—.’[24]

Election Agents and Sub Agents

Most of the hard work of private canvasses fell to the lot of local election agents and sub-agents rather than elite canvassers. These tended to be local businessmen, publicans, attorneys, estate stewards, and the like — that is, men who knew the community, the individuals in it, and voters’ personal histories and circumstances. As canvassing took them away from their employments, they were paid between 1½ and 3 guineas a day.[25] Identifying who was eligible to vote, especially in populous boroughs or counties, was always a challenge prior to Reform. Previous poll books, if relatively recent, could serve as useful canvassing books, as they not only indicated voters’ past preferences, but might also include the voters’ address and occupation. No matter how comprehensive an old poll book might be, howver, political intelligence gathering and local rumour always unearthed other potential votes. The breathless canvassing instructions and updates that Lady Susan Keck fired off to Revd Thomas Bray in August 1753 captures both the discovery of voters and the need for speed in securing their support:

I want a List of oxford freeholders Bishop of Stourton and his son, both votes for oxford have promised us; I have a notion that a man that keeps a shop opposit to St. Marys his name something like Cront, is a vote, he had a part of an Estate at Radford with one Martyn, That is a Minor. he is a Confectioner, pray enquire after him, I believe the confectioners (sic) name is Court. Canvass him instantly — their is one Lamuel[?] Robinson Jeweler in the High Street Islington by London That I am told is an Oxford Voter I will send after him and let you know — I have the promise of one Crosster a freeman of oxford, he is a wondering Journeyman Butcher, and Some time since passed himself as a Voter for the County, but at last confesed the truth, and said he belonged to The Parish of St Peters and was a freeman and if we wanted him he wou’d be with us.[26]

While canvassing urban voters could be relatively straightforward, as their membership of political clubs or personal political preferences might be well known, particularly in small towns, county contests were always more challenging, not only because counties were so much larger and more diverse, but also because it was vital to know which landholders had influence and where they stood politically. Consequently, having someone reliable on the ground who could map out these allegiances was important for the local committee and also for the politicians at Westminster. In the autumn of 1763, with the duke of Beaufort and the earl of Berkeley still minors (aged eighteen and nineteen, respectively) and a by-election triggered by the death of one of the sitting Members, Gloucestershire politics was of decided interest to the duke of Newcastle’s Whig Administration in London. Although the old Whig/Tory allegiances still lingered in Gloucestershire, John Pitt’s breakdown of the key supporters of the two rival family interests — the Beauforts and Berkeleys (with notably the widowed Lady Berkeley heading her family interest) — was forwarded to Newcastle’s closest political colleague, Lord Hardwicke. Pitt made a point of telling Hardwicke that this election would be based on a personal quarrel, not on political allegiances; conseqeuntly, he said that he would therefore await directions from Hardwicke before siding with either of the candidates.[27]

| For Sir William [Codrington] | For Mr Southwell |

| Lady Berkeley | Duke of Beaufort |

| Lord Chedworth | Lord & Lady Talbot |

| Lord Ducie | Lord Bathurst |

| Lord Gage | Colonel Berkeley & Corps |

| Lord Tracy | Mr Dutton |

| Robt & Thos Tracy | Sir John Gyn |

| Mr Barrow | Sir Francis Fust Jr. |

| Majority of Voters in & about Glocester (sic) | Sir Onerus[.] Paul |

| Dr Tewkesbury | Lord Colerain |

| Mr Guin | Majority of Voters in & about Bristol |

| Mr Colcheester | Do Cirencester |

| Mr Jones | Mr Masters |

| Mr Kingscourt | Mr Snell |

| Gen; Whitmore | Mr Bathurst |

| Mr Chamberlain | Mr Licence |

| Mr Hayward | Mr Windam |

| Mr Savage | Mrs Lamb |

| Mr Prinn | Mr Probyn |

| Mr Hyet | Mr Foley |

| Mr Stevins | Mrs Chester |

| Mr Delabere | |

| Mr Crawley | |

| Mr Yates | |

| The Clothiers Divided |

Knowing the political allegiances of the local landowners was important as it was customary election etiquette to respect a landowner’s and/or leaseholder’s political preferences and obtain his or her permission before canvassing their tenants.[28] Lady Susan Keck’s impatience with Lord Guilford during the Oxfordshire campaign led her to breach this convention in 1753. Guildford had adopted a position of studied neutrality in relation to his tenants’ votes because he was unwilling to upset his good relations with his neighbour, the Old Interest (Tory) candidate Sir James Dashwood. As a result, he had not instructed his agent to conduct a vigorous canvass for the New Interest (Whigs) on his Banbury estate. Never one to let good votes slip away if they could be had, Lady Susan sent one of her own people out to canvass Guildford’s tenants at Wardington without first getting his consent or the consent of the local squire, George Denton. A brouhaha promptly ensued. Denton was furious that Lady Susan had dared to conduct a canvass under his nose without his approval and Guilford fired off a letter that Lady Susan described to the leader of the New Interest in the county, the duke of Marlborough, as ‘a Barol of Gun powder’.[29] Denton, she claimed, was ‘raging mad’ because he had been shown up by the canvass: ‘their is not a Child of five years old in his Towne, that dont call Marlbro’ in his face’.[30] She reminded Marlborough that Guilford’s own steward, Watson, had not only allowed the canvass to take place, but had also himself previously, if ineffectually, canvassed Wardington for the New Interest:

tho’ Watson show’d spirit and a proper behaviour, with intention to preserve the Votes, Yet, it is certain, that he did not get one of them, and I do assure Yr. Grace, I dont believe any body cou’d have managed this thing but the Man that did it, who has Substantial relations that lives at Wardington, and is himself a cleaver fellow, to whom a great deal that we have done, has had been owing, with Yr. Graces permission to use Yr. Name, which goes as Currant as the Coin of the Nation, but still, tis best to have it managed by sensible people, and I have found great difference of Success by those I have employed.[31]

Lady Susan was wholly unapologetic for the breach of etiquette because her agent, who had substantial family connections in the village, secured the votes of eighteen of Denton’s twenty-three freeholders for the New Interest. When Guilford insisted that Watson apologise to Denton if he wanted to keep his place, she intervened again, promising Watson that that Marlborough ‘wou’d speak to his Lord —’.[32] When Watson then still refused to apologise, she stepped in herself to persuade him to apologise herself.[33] Presumably she succeeded, as Lord Guilford was placated.

It was the agent or sub-agent’s job to secure the votes of uncertain, truculent, mutinous or venal voters and personal connections or knowledge of the voters could make all the difference. At best, personal knowledge of voters might facilitate a quick, easy canvass that satisfied both the voter and the agent; at worst, it dredged up old animosities and feuds, and resulted in repeated and increasingly intimidatory and coercive encounters. The latter might be characterized by threats of eviction, visits from the bailiff, the confiscation of goods for debt, and assorted menacing warnings about the voter’s future livelihood or their son’s future career possibilities.

Examples of Voter Resistance

As the above image demonstrates, private canvasses could take place anywhere people met — be that in the public spaces of the town (the streets, shops, taverns, places of worship, and so on), or in the domestic space of the home. The sheer persistence of some canvassers, and their willingness to pursue voters quite literally to their bedsides, is remarkable, but the dynamics of power shifted subtly when canvassers entered people’s homes and may have encouraged independence or resistance. These final two examples, taken from depositions given to the select committees considering the controverted elections of Taunton (1830) and Camelford (1819), provide relevant examples.

Mary Godfrey Treby[34]

Taunton was a substantial potwalloper borough where 739 inhabitant householders had polled in 1826.[35] The contest in 1830 between General Peachy and Edward Bainbridge was for control of the second seat in the borough. Peachy was a Tory would go on to lose by nearly sixty votes to a stranger to the borough, the rich London banker and pro-reform Whig, Edward Bainbridge. Peachy promptly petitioned, charging Bainbridge (ultimately unsuccessfully) with bribery and corruption.[36]

Bainbridge was a hands-on candidate and, perhaps because he was new to the borough and had plenty of money at his command, his agents were enthusiastic and persistent canvassers. One of these was the local publican, John Upham. His attempts to secure the vote of Mary Godfrey Treby’s husband infuriated her to the point that she volunteered to act as a witness against him.[37] Mary was an incomer to Taunton, a French woman who had married a local tailor and set up as a washer-woman, employing local women who came to her house and worked under her supervision. She had little time for Upham, possibly because her husband had had financial dealings with him in the past, but chiefly because she deemed his behaviour ungentlemanlike, intrusive and impolite.

When Upham came to canvass her the first time, he entered her house and offered her a sovereign if she would ‘make my husband in a mind to vote for Mr. Bainbridge’.[38] She was angered by his effrontery and ignored his request. He repeated the canvass two days later, once again offering her money for her husband’s vote. She had, as informed the Select Committee later, told him that she was busy and that her influence could not be bought:

No Mr. Upham, I have got too much bother on my work; I have plenty of trouble of my own, and I did not take notice of such a little trifle as that, and I said he would vote for who he liked.[39]

Upham’s lack of respect for her and for her house as a place of work made her especially annoyed: ‘he made fun with my washer-woman; and I do not like gentlemen to come in, and make fun with my working woman’.[40] Just what sort of ‘fun’ Upham was suggesting remains unclear, but it may well have been ribald, as Mary was asked at the trial if he had also ‘joked’ her about ‘going upstairs’.[41] As a result of Upham’s behaviour, she called in a local attorney just before the polls closed and made a statement to him. This led to a final outburst from Upham when he discovered that she would be going to London to give evidence against him. He had stormed over to her house, furious that she would dare to testify against him. As she made clear to the Select Committee, however, she deemed Upham’s behaviour to have been ungentlemanly and this final ‘abuse’ in her own personal space was simply unacceptable: ‘I think it is very improper for a gentleman to come to my house in that way … Swearing and cursing, all sorts of wicked words not proper to be used’.[42]

Joseph Bond — Camelford, 1818

Joseph Bond’s experiences during the Camelford election of 1818 are an indication of just how persistent canvassers could be during a particularly close election. Camelford was a small Cornish borough, where the vote lay in resident freemen paying scot and lot (c.25+ voters after 1796).[43] In 1818, the Whig earl of Darlington, who had purchased a near controlling influence in the borough in 1815, faced his first electoral challenge when a number of pro-Administration candidates put themselves forward. The contest for the borough, given the limited number of votes, proved to be nasty and corrupt. Darlington’s candidates, his son-in-law Mark Milbank and the Scots lawyer Bushby Maitland, were eventually elected by three votes, but the outcome was challenged on the grounds of bribery, corruption and intimidation by the mayor. The Select Committee, which would take the unusual step of sending two witnesses to Newgate for providing false evidence, declared the election void in April 1819.[44]

Joseph Bond was a carpenter and one of a number of freemen in Camelford who was a member of a loosely constituted political club, the Bundle of Sticks, which was opposed to the Darlington interest.[45] As a result, he was canvassed at least four times in the month before the election in 1818. The first canvass took place on 17 May as Bond was walking to church. The mayor, Matthew Pope, Jr, who was leading the campaign for Darlington interest in the borough (and who would also be the returning officer at the election), fell in step with him and ‘advised me to take care of myself, and to vote for those gentlemen in the interest of Lord Darlington, who had lately canvassed the borough … and not to pay attention to fools, as I was on the wrong side of the last election’. Pope went on to issue him with an only lightly veiled threat: ‘Then he advised me to take care of myself, as I had a large family, and not to act foolishly; and if in case I voted for Lord Darlington’s friends, I, as long as I lived, should never want a friend’.[46] Bond was not intimidated, but he was provoked by Pope’s threats. Before he entered the church, he took out his carpenter’s pencil and notebook and made an immediate record of what Pope had said. The fact that he would go on to record the later canvassing encounters as well, and then willingly report them to the Select Committee, suggests that he had determined not to vote for Darlington’s candidates from the outset of the campaign. He claimed to the Select Committee, however, that he had not actually made up his mind until after the final public canvass shortly before the election, but that he did not like to have his political independence challenged in this way.

The second canvass took place on 11 June when Bond was fixing the front door of the sadler’s shop. Pope was in the shop at the time and went over to Bond purposefully. He claimed, loudly enough that the sadler and another customer overheard the conversation, that Darlington needed only two more votes for a majority. He then threatened Bond again:

Then he asked of me whether I had made up my mind who I was going to vote for, I told him no. He says to me, he wished to know whether I would vote against Lord Darlington’s party, or for them? I said I would not answer that question then. Then he said if I did not vote for Lord Darlington’s friends, I and my family should be ruined for ever.[47]

Pope accosted Bond for the third time the following day, as he was walking past Pope’s shop. Pope went out into the street to ask Bond if Darlington’s steward, Dent, who was acting as his agent, had spoken to him. Pope claimed that he had been speaking to Dent and told Bond that he ‘might be taken care of’ if he supported Darlington’s candidates: ‘a few hundreds in my family would do me a great deal of good’.[48] As votes were reputedly going for between £300 and £600 pounds in Camelford, and Bond had a large family, this would have been a substantial contribution to his family finances. Dent, however, did not make Bond an offer (at least at that time) and Bond persisted in not saying whether he would support the Darlington interest.

The final canvass took place on the night before the election — or, more accurately, in the very early morning of the election itself. Both parties and their supporters had been at the Darlington Inn and Bond had been drinking with a group of men in the bar. At this point, Darlington’s steward, Dent, stepped in. He walked home with Bond at 11 p.m., ostensibly in an effort to keep him sober enough to vote the following day. Just how drunk Bond might have been is unclear from the depositions, but Dent was obviously not convinced that he had secured Bond’s vote. Rumours were flying about the town, though, and a rumour had been started that other members of the Bundle of Sticks club had switched sides and decided to vote for the Darlington interest. As a result, somewhere between 2 and 3 a.m., when Bond was asleep upstairs with his wife, his neighbour Gayer entered the bedroom and woke him up to assure his that the rumour was false: he and a number of other Bundle of Sticks’ supporters were not switching sides. Just as he was leaving, at about 3 a.m., Dent entered the bedroom. He had come to canvass Bond yet once more. He invited him to get dressed and go over to the big house (Dent’s house) where he would be treated to coffee.[49] Dent stayed for about a quarter of an hour (resulting in Bond’s wife being decidedly and understandably annoyed), and was finally seen downstairs and out the door by Bond, who was still dressed only in his nightshirt. Having sent Dent on his way, Bond then returned upstairs, got dressed and went to join one of his colleagues from the Bundle of Sticks before voting later that morning against Darlington’s candidates.

Bond’s votes had personal consequences. Dent gave him notice at Michaelmas that he was to be evicted from his shop — presumably he also lost Dent’s and Darlington’s custom as a result as well, at least in the short term — but Bond’s testimony to the Select Committee the following spring indicated both his resolve and his political understanding.[50] When asked by the Select Committee why he had voted as he did, and why he had made notes of all of these encounters and gone to a solicitor ‘directly after the election passed’, his answer was clear: ‘As I thought that we were put upon like in the election, I thought I must try to make my redress somewhere to be rights, as I had voted … In the borough a freeman ought to have his rights of speaking and thinking’.[51]

This piece draws in part upon an earlier discussion of canvassing that can be found in Elaine Chalus, ‘Gender, Place and Power: Controverted Elections in Late Georgian England’, in James Daybell and Svante Norrhem (eds), Gender and Political Culture in Early Modern Europe, 1400–1800 (London: Routledge, 2017), 179–98.

[1] David Eastwood, ‘Parliament and Locality: Representation and Responsibility in Late-Hanoverian England’, Parliamentary History, 17/1 (1998), 76; Frank O’Gorman, Voters, Patrons and Parties: The Unreformed Electorate of Hanoverian England, 1734–1832 (Oxford: OUP, 1989), 67. The following discussion of canvassing draws upon O’Gorman, 90-105.

[2] BL. Ms Coll. Althorp. G. 276: Dwgr Css Spencer to Ld Spencer, n. pl. [St Albans], 23 Dec. 1783; Robin Eagles, ‘The Mince Pie Administration or Plum Pudding Billy’, History of Plariament Blog, 15 Dec. 2022: https://thehistoryofparliament.wordpress.com/2022/12/15/the-mince-pie-administration-or-plum-pudding-billy/ [accessed 3 July 2023].

[3] Quotations here and below from this letter: BL Ms Coll. Althorp F.14: Spencer to Dwgr. Css. Spencer, Althorp, 20 Mar. 1784.

[4] ‘Northampton’, History of Parliament: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1754-1790/constituencies/northampton [accessed 3 July 2023].

[5] David Eastwood has spoken of the ‘highly visible, frequently intimate world of the parish’, when examining public life in rural England in this period: David Eastwood, Government and Community in the English Provinces, 1700-1870 (Houndmills: Macmillan, 1997), 30.

[6] Exeter College, Bray Papers, L. IV. 7 B. no. 37: Ly Susan Keck to Revd Thomas Bray, Great Tew, 21 Oct. 1753. Published with permission of the Rector and Fellows of Exeter College, Oxford.

[7] BL Add. Ms 41,152, Townshend Ser. II, vol. xiv, fols 17d–18, 30.

[8] Somerset Archives and Local Studies (Taunton) [hereafter SRO]: DD/WM 44: W. Taverner to Clement Tudway, London, 25 Sept. 1765.

[9] Idem., W. Taverner to Clement Tudway [London], 19 Oct. 1765.

[10] Idem., W. Taverner to Clement Tudway, London, 5 Nov. 1765.

[11] Dorset County Chronicle, 2 Sept. 1830. The duke of Buckingham’s records for the 1832 Buckinghamshire county election include payment for local 104 men; two bands of 18 and 14 men respectively, 8 flagbearers and 64 stavesmen: Huntington Library, San Marino, CA, Stowe Papers, STG Elections Box 8(1).

[12] SRO, DD/X/WLM/3/C/1352, Disputed parliamentary Election, Taunton 1807: ‘In the House of Commons. Before a select Committee 10th. March 1807 … Brief for the Sitting Members ….’

[13] O’Gorman, Voters, Patrons and Parties, 95–6.

[14] Elaine Chalus, ‘Kisses for Votes? The Kiss and Corruption in Eighteenth-Century English Elections’, in Karen Harvey (ed.), The Kiss in History (Manchester: Manchester UP, 2005), 122–47.

[15] Trial of the Taunton Election Petition, before a Committee of the House of Commons, February 23rd. 1831 (Taunton: W. Bragg, 1831), 207.

[16] Trial of the Taunton Election Petition, 206–07.

[17] Essex Record Office, D/DFg Z1. Correspondence of Sir Robert Smyth, Bt, MP, Colchester, 1777–1802: Duke of Dorset to Sir Robert Smyth, Knole, 22 March 1780.

[18] Advice from Horace to Lady S—s—n (1753).

[19] ‘Boots and Shoes: Or, Advice to a Lady’, Oxfordshire Contest, 44.

[20] ‘Boots and Shoes: Or, Advice to a Lady’, 43–4.

[21] ‘Sir Wm Musgrave to Ld Carlisle, 1 Dec, 1767’, HMC Carlisle, 221.

[22] Portland Papers, University of Nottingham, PwF 9164: Mary, Marchioness of Rockingham to 3rd Duke of Portland, [4 Mar. 1768 (rec’d)]. Lady Kath (née Lady Catherine Stewart, daughter of the 6th earl of Galloway) had married in 1752, so it is likely that she was in her mid-to-late thirties in 1768.

[23] For further details on the Westminster election and the kisses for votes episode see here and here.

[24] BL Ms. Coll. Althorp F. 42:Dwr Css Spencer to Mrs. Howe, n. pl. [St Alban’s], 2 Apr. 1784.

[25] E. A. Smith, ‘The Election Agent in English Politics, 1734–1832’, English Historical Review, 84:330 (Jan. 1969): 33–35.

[26] Exeter College, Bray Papers, L. IV. 7 B. no. 27: Ly Susan Keck to Revd Thomas Bray, n.pl. [probably Great Tew], [19 Aug. 1753].

[27] BL Add. Ms 35,692, fols. 157–8: John Pitt, to Ld Hardwicke, Gloucester, 8 Oct. 1763. The chart below at fol. 158.

[28] For a more detailed examination of Lady Susan Keck’s involvement in the Oxfordshire election of 1754, which also includes an earlier version this example, see Elaine Chalus, ‘My Lord Sue’: Lady Susan Keck and the Great Oxfordshire Election of 1754’, Parliamentary History, 32:3 (2013): 443–59.

[29] BL Add. Ms 61,667, fol. 151: Lady Susan Keck to Marlborough, Great Tew, 24 Jan. [1753].

[30] Idem., fol. 153: Lady Susan Keck to Marlborough, [n.pl.], 25 Jan. [1753].

[31] Idem., fols 153–4: Lady Susan Keck to Marlborough [Great Tew], 25 Jan. [1753].

[32] Idem., fol. 158: Lady Susan Keck to Marlborough [Great Tew], 27 Jan. [1753]; see also f. 167: Lord Guilford to Lady Susan Keck, London, 27 Jan. 1753.

[33] Idem., fol. 159v: Lady Susan Keck to Marlborough [Great Tew], 29 Jan. 1753.

[34] This example draws upon an earlier version published in Elaine Chalus, ‘Gender, Place and Power: Controverted Elections in Late Georgian England’, in James Daybell and Svante Norrhem (eds), Gender and Political Culture, 1400–1800 (Routledge, 2016), 179–95.

[35] Parliamentary Papers (1830-1), X, 8.

[36] Terry Jenkins, ‘Taunton’ in The History of Parliament: The House of Commons, 1820-1832, ed. by D. R. Fisher (2009): http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/constituencies/taunton [accessed 9 October 2014]; Trial of the Taunton Election Petition, 298.

[37] For Mary Treby’s evidence, Trial of the Taunton Election Petition, pp. 90-6. Her testimony is corroborated by her washer-woman, Sarah Lenthall, 96-8.

[38] Trial of the Taunton Election Petition, 90. Upham wants Mr. Treby to give him ‘one word’, i.e., one vote, for Bainbridge. He uses the same language when he (also unsuccessfully) canvasses Mary Baker on the second day of the poll. He asks Mary if her husband had promised his vote — had he ‘given a word’? Mary replied, ‘yes one, and I had given the other’. Although she had no legal right to her husband’s second vote, her response reflects the fact that the vote was frequently viewed as family property and that wives had a say in how it was exercised. For further examples of this see Cragoe, ‘Jenny Rules the Roost’.

[39] Trial of the Taunton Election Petition, 90.

[40] Trial of the Taunton Election Petition, 93.

[41] Trial of the Taunton Election Petition, 95.

[42] Trial of the Taunton Election Petition, 91.

[43] R. G. Thorne, ‘Camelford, 1790–1820’, History of Parliament https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/constituencies/camelford [accessed 6/07/2023].

[44] Ibid.

[45] This example is drawn from the testimonies given to the Select Committee and published in Report from the Select Committee on the Camelford Election; together with the special report from the said committee; and also, the minutes of evidence taken before them. (London, 1819).

[46] Idem., 9.

[47] Idem., 10.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Idem., 91, 101–103.

[50] Idem.,179–80.

[51] Idem., 12.