Steve Poole looks at the theatre and occasional violence of chairing ceremonies [20-minute read]

At the conclusion of the extremely violent and contentious election for Coventry in 1780, the victorious Tory candidates, Lord Sheffield and Edward Yeo were hoisted onto wooden chairs and triumphantly paraded through the streets. It had been a tough contest, fought amidst accusations of corruption orchestrated by the Whig corporation and its patron Lord Craven, and finally decided on petition in 1781. And the greatest measure of Sheffield and Yeo’s victory, it seemed, lay in that simple act of chairing. As one doggerel poet had it,

Now see the glorious Day appears

Let every Churchman banish Fears

Brave YEO and SHEFFIELD in their Chairs

Are our elected Members …

In spite of Craven and his Crew

And what his bloody Mob can do

We’ll let them know we’re right True Blue

And chair our glorious Members[1]

Although the right to vote was severely restricted in the unreformed parliamentary system, it has long been recognised that there were many ways in which non-voters were encouraged to take part in election rituals.[2] Popular participation began on day one with the customary junketing that greeted the first arrival of each candidate in the constituency, and continued with the show of hands that triggered the call for a poll at the nomination ceremony.[3] But perhaps the most inclusive of all election rituals was the triumphal chairing of the successful candidates once the result had been publicly announced.

Chairings as performance: spectacle and disorder

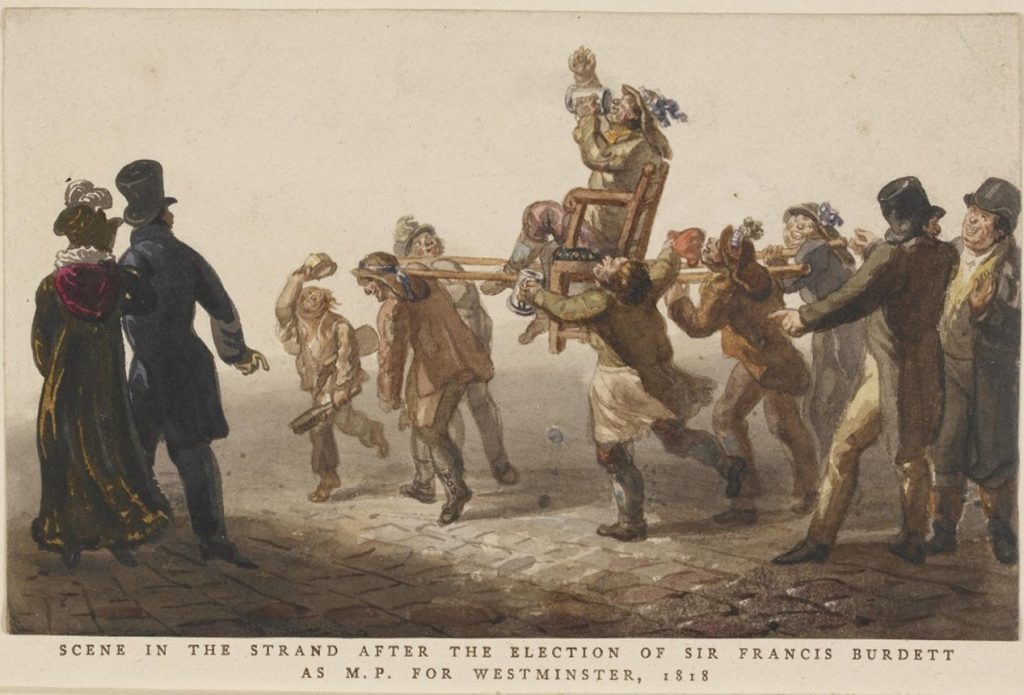

In James Vernon’s view, a heavily stage-managed chairing, ‘at once romantic, tragic, comic and ironic’ was ‘the grand finale… the ceremony that ended all ceremonies’, the symbolic elevation of the constituency’s elected representative.[4] Provided chairings were routed through the least socially contested central streets, observes Mark Harrison, they were recognised in most constituencies as a right, ‘whatever the political complexion of the party concerned’, adding ‘The authorities would police the event but, nevertheless, it would rarely be regarded as posing any kind of threat to the city’s social stability’.[5] They became increasingly expensive to stage as the scale and cost of decorations and fixtures, and the hiring of costumed musicians, rose inexorably. Local tradesmen expected handsome rewards for their labour in the manufacturing of the ceremony and non-electors expected showers of coins from victors as they passed. However, their recognition as a legitimate political ritual was no guarantee that chairings would be easy to police. Public audiences, never entirely predictable, were not always content to quietly spectate. They might even be encouraged to join in, heightening the celebratory mood and lending the ritual an air of civic cohesion. This could be carried to quite elaborate extremes and required careful pre-planning if disorderly crowd behaviour was to be avoided. The chairing of the prominent reformer, Sir Francis Burdett at Westminster in 1818 for instance, was intended not only as a celebration of his personal victory but of the city’s consensual support for constitutional liberty. Pedestrians, horsemen and carriages were allotted ‘different stations’ in a grand procession regulated by signals made by discharging rockets and displaying flags. Coloured banners represented each parish in the constituency and some displayed progressive slogans: ‘Magna Charter’, ‘Purity of Election’, ‘Burdett and Reform’, and ‘Trial by Jury’.[6]

The Whig MP, Henry Bright’s chairing at Bristol in 1820 eclipsed even the theatricality of Burdett’s victory two years earlier. Not only did it feature hundreds of representatives of Bristol’s trades carrying giant and carefully crafted emblems, flags and banners, but the victor’s ‘chair’ (more an immense sleigh mounted on a platform) was decorated,

front and rear, with four emblems, in gold, of the Union of the Whigs of Bristol, surmounted by doves, each bearing an olive branch in his mouth. The whole car was lined with crimson velvet, tufted with blue; the outside scarlet decorated with heraldic bearings, on the sides, the arms of the member, encompassed by wreaths of laurel; in front, in relief, the Royal Arms; on the back the City Arms…[7]

Bright’s election as Whig candidate was uncontested and his victory inevitable, so planning for a ceremony of such magnitude could begin as soon as his selection was confirmed. In this case, the sheer verve of the choreography suggests its organisation must surely have taken the full fortnight between his selection and his return. It would certainly have been difficult to plan at short notice only after the result was known and any rivals defeated.[8] A large panoramic pen, ink and watercolour depiction gives a sense of the scale and variety of the procession.

The ever-increasing cost and extravagance of these early nineteenth century processions, together with the largesse of scattering coins amongst the crowd, was finally brought to an end by the 1854 Corrupt Practices Act, after which the few chairings that survived at all adopted a much more modest style.

Arguably, without some measure of popular participation, an elaborate public chairing like Bright’s would have been quite meaningless. As Frank O’Gorman has noted, the election chairings were not just a ‘manifestation of political commitment and political loyalty’, but of ‘social prestige’ too, and they would enjoy little impact without the approving participation of spectators.

In the unreformed system of course, a candidate’s popularity with small and unrepresentative electorates was no guarantee of popularity with the unenfranchised majority. In this sense, chairing was as provocative as it was triumphalist, and public opposition might be easiest to take if restricted to sullen indifference. ‘The magisterial party have not the hearts of the people…’ observed a defeated pamphleteer at Newcastle in 1775. ‘The weak huzzas and thin train of attendants at the chairing of the members tells them so – and their appointing a numerous band of constables to precede the procession proclaims they know it too’.[9]

As this dismissive commentary suggests, the careful policing of chairing ceremonies was essential because it was easy for indifference to spill over into physical hostility. Processions were therefore often attended by horsemen and sometimes special constables, to ‘prevent the confusion and irregularity which might otherwise occur’.[10] At the Norwich by-election in 1794, Pitt the Younger’s war minster, William Windham, was struck on the head by a well-aimed stone as he was chaired around the castle mound. Although he leapt gamely from his chair on that occasion to take his assailant into custody, it was judged necessary to surround his chairing at the general election two years later with thirty ‘gentlemen on horseback… which, with the freemen and freeholders, Sheriff’s posse, music etc., nearly formed a circle round the market place’. Even then, Windham rode his luck for, ‘one man was desperate enough to throw a large stone at Mr W., which fortunately missed him’.[11] Although local authorities strove to control and limit crowd activity before, during and after a chairing more riotous outbreaks of factional fighting were not uncommon, their familiarity alluded to most famously by the ‘Chairing the Member’ picture in Hogarth’s Humours of an Election series (1754-5).

Hogarth’s painting was certainly satirical but it was not a work of fiction. However impressive Bright’s triumphant chairing at Bristol in 1820 may have appeared, it had been preceded in 1807 by some of the most chaotic scenes ever witnessed at an election in the city. While the Whig member, Evan Baillie, was chaired without incident, the Tory, Charles Bathurst, was assailed by ‘a lawless and ferocious banditti’. He was almost knocked to the ground by a well-aimed stick in Broad Street, and then ‘attacked with such a shower of oyster shells, mud etc., that had he not descended from his chair, his life must have been in imminent danger’.[12]

Even though he had been elected for Nottingham without opposition in 1797, Sir John Borlase Warren’s chairing was ambushed by ‘a party of low fellows’ who ‘assailed the gallant Commodore and broke the chair in which he was carried to pieces’.[13] And following a boisterous contest at Lancaster in 1802, the provocative chairing of a successful candidate past the committee rooms of his defeated rival caused an ‘enraged mob’ to pelt the victors with volleys of stones, and they responded by smashing all the windows.[14] Measures designed to ameliorate ‘confusion and irregularity’ of this sort were not always confined to policing with ‘gentlemen on horseback’ however. At Boston, Lincolnshire in 1830, a year when party feeling over parliamentary reform was beginning to drive hard ideological divisions between parties, the two successful candidates, from opposite sides of the argument, tactfully agreed to take it in turns to be chaired, in an attempt to prevent the clashing of rival crowds. Their chairings were then followed by a consolatory ‘mock’ ceremony for the losing candidate, and disorder seems to have been successfully avoided.[15]

Mock chairings

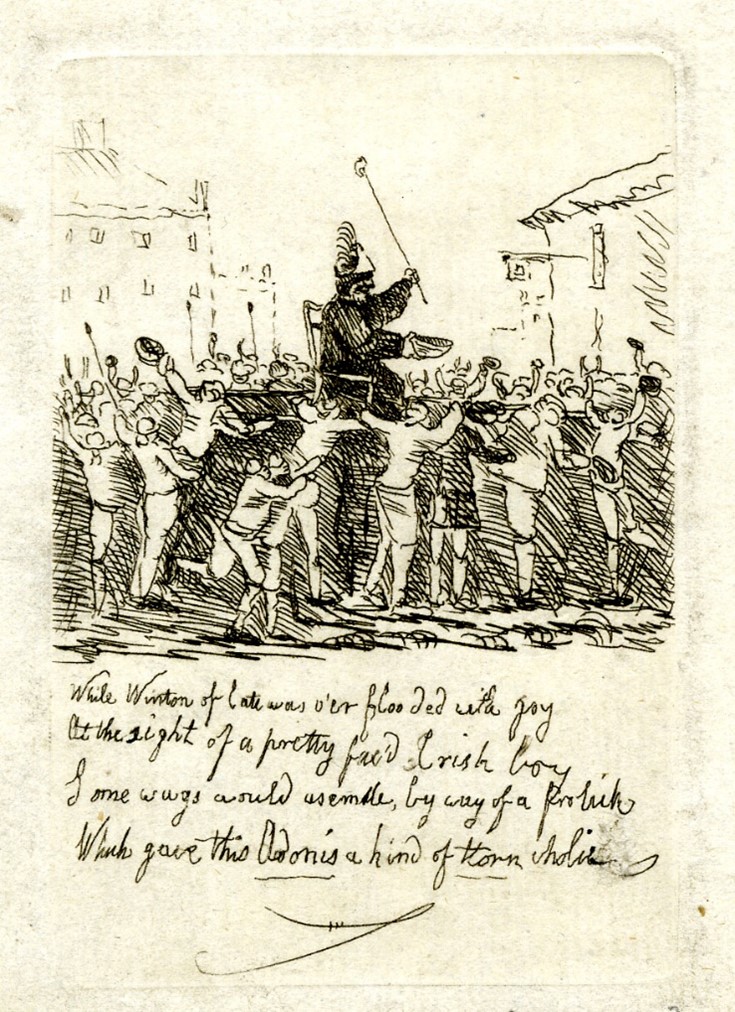

Although a fairly common feature of the electoral theatre, mock chairings were not always conducted in the polite and consolatory spirit witnessed at Boston. They might also be staged without elite sanction, in opposition to the election result, to lampoon the returned members and ridicule the limitations of the franchise. Some took the form of charivari or skimmington, obliging an unpopular politician to be paraded in effigy, usually by non-electors, to the accompaniment of rough music. The Irish orator Henry Flood was treated to this indignity in the pocket borough of Winchester, a constituency controlled by the Duke of Chandos and in which only the Corporation were entitled to vote. Chandos gifted him the seat at a by-election in 1783, but his election drew noisy protests from the Corporation’s political opponents in the city and Flood was forced to look elsewhere for a nomination at the general election a year later. His abandonment by his patron was satirised in a cheap engraving, depicting his mock chairing in a fool’s cap and carrying a punch bowl, escorted by a rough looking crowd.[16]

This print bears some resemblance to a scene being played out in the background of William Hogarth’s The Stagecoach: A Country Inn Yard at Election Time (1747) in which the effigy of a baby is being paraded in a mock chairing by a crowd armed with clubs. The child carries a rattle and an ABC primer but in the print’s earliest stages was surmounted by a placard reading ‘No Old Baby’. There is some uncertainty about the point of the satire. Ronald Paulson sees it as an effigy of a youthful Jacobite pretender to the throne (the ‘Babe of Grace’ claimed by James II as an heir), while Sean Shesgreen sees it as John Child Tylney, the twenty-year old candidate for Essex. What we can say with certainty however is that Hogarth was playing on popular familiarity with the idea of a mock chairing, the central comedy of which lies in the tension between pomposity on the one hand and ridicule on the other.[17]

A third kind of mock chairing might take the form of plebeian parallel. As the official chairing of popular candidates became steadily more respectable, spectacular and stage-managed, labouring class processions were sometimes enacted, perhaps spontaneously and with rather less pretension. Some were rooted in long-standing traditions, quietly disapproved of by the elites whose ceremonial culture they mimicked, but sufficiently robust to withstand reform. The Footmen serving Westminster Hall for instance, customarily elected ‘what they call a Speaker amongst themselves’ at the opening of every new Parliament, roughly chairing rival candidates around the Hall, preceded by a mock Mace. Ribald performances of this kind did not always end peacefully as parliamentarians found to their cost in 1735 when the chairing of rival Court and Country factions led to fighting in the corridors of the Court of Requests. ‘There were several Heads broke and some so dangerously wounded that their lives are in danger’, it was reported. ‘The Battle began about Two and it was near Four before the Tumult was appeas’d’.[18] Despite their disorderly nature, popular chairing ceremonies like this survived well into the following century, as the contemporary illustration of a crowd celebrating Burdett’s victory at Westminster in 1818 clearly demonstrates. .

Whatever their complexion, mock chairings survived because, as O’Gorman puts it, they ‘represent the coexistence of independent traditions of popular culture with those of the political nation’.[19] In essence, elite tolerance signalled, however begrudgingly, the legitimacy of popular agency within a political culture from which it was excluded in practical terms; a recognition, at least in theory, that parliament, and its representatives, were answerable to ‘the people’.

But what were the limits of elite tolerance and forbearance? And how far might election crowds go if given free reign? We turn now to perhaps the most nuanced variation on the chairing ritual, the destruction of chairs by violent crowd, an intervention that became a regular tradition in some constituencies, and its tacit tolerance by the authorities. To fully experience this phenomenon, we must take a diversion to Worcester.

Chair-breaking

At Worcester, physical confrontations were a customary part of the ceremony. Reporting the chairing of members after the election of 1818, the Worcester Journal noted, ‘The usual custom of destroying the chair before the Members had descended from it, took place near the Guildhall’. Quite how long this ‘usual custom’ had been in existence is not clear. It does not appear to have taken place in 1806, for example, but by 1812 it was being referred to as something that was ‘always’ done.[20] However venerable the practice, however, tolerance was here extended not to a mere parallel ceremony, but to an assertive and physical interference with elite ritual. Newly elected members in elaborately designed and decorated ‘chairs’ would set off on an extensive circuit of the city fully aware that before they reached the end of it, the Worcester mob would ambush the procession, throw them to the ground and destroy the chair. It was not a question of political allegiance; Tories and Whigs alike were treated to the same indignity at every election, regardless of whether it had even been contested.

To think of chair-breaking at Worcester in simple terms as riot would be missing the point. As the city’s nineteenth-century chronicler put it, matter-of-factly, on the closing moments of the 1818 contest, ‘the two members were chaired as usual the day after the election had concluded and the chairs demolished by the populace. According to their ancient prerogative and right’.[21] Although the Corporation and the electoral committees and parties all publicly regretted the practice and occasionally did their best to evade the mob, constables were never introduced, the Riot Act never read, and criminal charges never laid against the perpetrators. Only the ornately fitted out chairs were targeted, and no other property damaged except on rare occasions where the crowd felt cheated by unexpected and evasive route changes.

Chair breaking was not an act of protest, either against individual candidates and parties or against the exclusivity of electoral privilege. Rather, we might see it as a playful skit upon popular notions of accountability, and a literal reminder that members of parliament were answerable to electors and non-electors on pain of ‘losing their seats’. It was perhaps also about the taking of trophies, as a kind of memorabilia, at the conclusion of a significant and expensive political jamboree. ‘It has been a long custom with the populace of this city and one that has been duly honoured in the observance’, noted the Morning Post of the Worcester by-election in 1816, to break the chairs, ‘for the purpose of preserving such reliques as may remind them of the circumstance in after years’.[22]

Chair-breaking was not a custom unique to Worcester but no other constituency clung to it with quite so much determination. Similar traditions were practised at Guildford, and at Monmouth, although it is unclear whether they were observed at every election. Chairs were occasionally destroyed at York and one or two other places too, but after, rather than during, the ceremony. The York crowd were certainly not indulged to the same extent as Worcester’s, for in 1841, after attacks were carried out against party banners as well as the two chairs, constables moved in and threw several ringleaders into the lock-up for riot. They were quickly released by order of the magistrates, ‘otherwise the spirit that pervaded at the moment might have led to more serious circumstances’. At Taunton in 1847 ‘the rabble’ (a Tory crowd in this case) tried to destroy the Liberal candidate’s chair and banners after he took the seat by just 12 votes, but this seems to have been an isolated incident.[23]

What set Worcester apart from anywhere else in the country was the apparent inevitability of crowd action, coupled with an inability or unwillingness to suppress it on the part of the authorities. Although an established practice by 1812, it was nevertheless considered regrettable because in that year it was prevented by the refusal of the candidates to be chaired. To prevent the usual ‘confusion’, they opted for open carriages instead and there seems to have been no trouble.[24] At the following by-election in 1816, Lord Deerhurst, the sole candidate, was chaired through the city as usual but by an unusual route. But if his committee hoped such a small break with tradition might deter the crowd they were to be disappointed for ‘an outrageous attack was made, near the Guildhall, upon the men who bore the chair, which compelled Lord Deerhurst to quit it, immediately upon which the populace rushed in and in a few minutes deprived it of all its splendid honours’.[25] Despite the successful experiment of 1812, chairs were intercepted and destroyed at each subsequent city election and by 1830, the Worcester Herald, for one, had had enough:

Agreeably to the senseless and equally perilous custom upon such occasions, the procession was not allowed to regain the spot from whence it had set out. Scarcely had it turned the corner at the top of Broad Street on its way back to the Town Hall, when the car was pounced upon by the surrounding rabble, the ‘sitting members’ unceremoniously unseated, and the whole fabric reduced in one moment to a wreck. Fortunately, the Hon, Gentlemen reached terra firma without injury.[26]

Violent ambush may have been customary, noted the Journal, but it was a senseless anachronism and best ‘honoured in the breach’.[27] The paper pressed the point a year later: ‘As we live in reforming times’, it reasoned, ‘we wish the “spirit of the times” would reform this foolish and dangerous practice’. Election committees were keen to modernise and improve the ceremony, but such ambition was difficult to reconcile with the destructive rights of the crowd. Successful candidates, it was decided after the 1831 election, should no longer be hoisted onto the shoulders of their supporters but ‘elevated on a trolly’ pulled by ropes, hopefully ‘preventing that scene of senseless outrage and peril in the destruction of the chair’. But it was to no avail. The procession was disrupted even earlier than usual, on arrival at the Cross, and ‘within a very few minutes the gay fabric became a perfect wreck’.[28]

Finally, in December 1832, after the first election of the reformed parliament, Davies and Robinson’s committees announced an end to the chairing ceremony, ‘in consequence of the great disappointment felt by a considerable portion of the inhabitants by the breaking of the chair before the procession had passed through the principal streets and from the accidents frequently taking place from this reprehensible custom’. Instead, both members were paraded together along the customary route but, as in 1812, in an open carriage, ‘tastefully fitted up… to resemble a canoe with an Egyptian scroll in front from which draperies were suspended, trimmed and ornamented with bullion fringe’ and drawn by six horses.

However, the crowd were in no mood for ornamental innovation. An initial attempt to attack the carriage was repelled by force and then, as the cavalcade returned from St John’s, the drivers veered suddenly and unexpectedly to the left after crossing the bridge, galloped up North Parade, turned right into the Butts and brought the Members safely back to the Hop Pole by the rear entrance. Cheated of the chance to finally confront the procession in Broad Street or at Cross, the crowd made a rush on the Inn, fought their way into the back yard and began stripping the silk and fittings from the carriage. Some rocks were thrown and at least one head injury sustained but once again they were beaten back and the carriage survived.[29]

In 1835, Robinson once again chose a carriage while the newly elected Mr Bailey selected a robust and ‘tastefully designed car’ of ‘unusual elevation’. There was one incident in New Street when two stones shattered the windows of the Rev Dr Redford’s house, narrowly missing the Reverend’s wife and injuring a servant woman in the eye. The chair was attacked and destroyed just as he arrived back at the Hop Pole, while Robinson’s party repeated the avoidance strategy of the previous election, turning from the usual route at the top of Broad Street and whipping the horses fast to the rear of the Star.[30] Bailey’s fancy car was rebuilt for the election of 1837, and although he was permitted to remain in it until his procession regained the Hop Pole, it was, once again, dashed to pieces as soon as he had been lowered to the pavement. It appears to have been the last time candidates’ chairs were destroyed during Worcester city elections.[31]

Conclusion

Despite acknowledging the importance of chairing as the closing ritual in Hanoverian parliamentary elections, historians have had surprisingly little to say about it beyond acknowledging that social division was as often the outcome as cohesion. But there remain a number of questions worth asking. Chairing is usually represented as nationally coherent in form and nature, as though the political culture that sustained it was untouched by local and regional nuance. What do we know about the relationship between customary chairing routes in British towns and the local politics of public space? And how did that relationship change over time as towns grew, demographics changed and populations expanded? How influential were local factors in the development of chairing as a component of British political culture? Was Worcester the only constituency in the country where the complete destruction of chairs played a regular role, and if so, where did that very particular ‘ancient prerogative and right’ come from? Given the mounting expense involved in the creation of the most spectacular chairing processions in the early years of the nineteenth century, why do we know so little about the afterlife of electoral material culture? How many museums and archives still hold election chairs (or parts of chairs) in dusty corners of their collections, as for instance at Stanford Hall or Hughenden Manor? Chairing processions enjoyed a very visible public presence and we need not doubt their capacity, on occasions, to pull communities together in celebration despite the clear unaccountability of ‘virtual representation’. Yet chairing was also a site of antagonism; provocative both to supporters of unsuccessful candidates and to the unenfranchised, for in celebrating the power and privilege of the political elite, it remained a public reminder of the inequalities of ‘Old Corruption’.

[1] A Song for the Chairing Day by an Old Woman who Loves her Church and King (Coventry 1780).

[2] An argument reiterated most recently by Malcolm Crook and Tom Crook, ‘Hoarse Throats and Sore Heads: Popular Participation in Parliamentary Elections Before Democracy in Nineteenth Century Britain and France’, in D. P. Cerezales and O. Lujan (eds.), Popular Agency and Politicisation in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Palgrave 2023), 171-193.

[3] John A. Phillips, Electoral Behaviour in Unreformed England: Plumpers, Splitters and Straights (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982); Frank O’Gorman, Voters, Patrons and Parties: the Unreformed Electoral System of Hanoverian England, 1734-1832 (Oxford: OUP, 1989); ‘Campaign Rituals and Ceremonies: the Social Meaning of Elections in England, 1780-1860’, Past and Present, 132, May 1995; ‘Ritual Aspects of Popular Politics in England, c.1700-1830’, Memoria y Civilizacion, 3, (2000); H. T. Dickinson, ‘The People in Parliamentary Elections’, in The Politics of the People in Eighteenth Century England (St Martin’s Press, 1994); James Vernon, Politics and the People: A Study in English Political Culture, c.1815-1867 (Cambridge: CUP, 1993).

[4] Vernon, Politics and the People, 95.

[5] Mark Harrison, Crowds and History: Mass Phenomena in English Towns, 1790-1835 (Cambridge: CUP, 1988), 159.

[6] Baldwin’s London Weekly Journal 11 July 1818.

[7] Bristol Mercury 13 March 1820.

[8] Terry Jenkins, ‘Bristol, 1820-1832’ in D. R. Fisher (ed.), The History of Parliament: The House of Commons, 1820-1832 (Cambridge: CUP, 2009).

[9] The Burgesses Poll at the Late Election of Members for Newcastle Upon Tyne (Newcastle 1775), 23.

[10] Frank O’Gorman, Voters, Patrons and Parties, 138.

[11] Norfolk Chronicle 9 July 1794; Ipswich Journal 28 May 1796.

[12] Hereford Journal 13 May 1807.

[13] Lloyd’s Evening Post 17 November 1797.

[14] Morning Post 21 July 1802.

[15] A Sketch of the Boston Election Comprising the Speeches of the Candidates… (Boston, 1830) xxviii-xxviv. Although the candidates were sharply divided, they all claimed independence from the party system as representatives of the Pink, Blue and Orange interests.

[16] For protests over Flood’s election at Winchester see Hampshire Chronicle 27 October 1783.

[17] Ronald Paulson, Hogarth Vol.2: High Art and Low, 1732-1750 (Rutgers University Press, NJ, 1992), 278-87; Sean Shesgreen, Engravings by Hogarth (Dover, NY, 1973), plate 59.

[18] Stamford Mercury 20 February 1735.

[19] O’Gorman, ‘Campaign Rituals and Ceremonies’, 111-2.

[20] Worcester Journal 25 June 1818; Morning Post 7 November 1806; Worcester Journal 15 October 1812.

[21] T. C. Turberville, Worcestershire in the Nineteenth Century: a Complete Digest of Facts Occurring in the County Since the Year 1800 (London 1852), 32.

[22] Morning Post 31 December 1816.

[23] For Monmouth, see the experience of Octavius Morgan, noted in Salmon, Electoral Reform at Work, 95; London Packet 12 January 1835; The Silurian 14 February 1841; York Herald 3 July 1841; Exeter Flying Post 5 August 1847.

[24] Worcester Journal 15 October 1812.

[25] Worcester Journal 26 December 1816.

[26] Worcester Herald 31 July 1830; 25 June 1818.

[27] Worcester Journal 5 August 1830.

[28] Worcester Herald 7 May 1831; Worcester Journal 5 May 1831.

[29] Worcester Herald 10 December 1832; Worcester Journal 13 December 1832.

[30] Worcester Herald 10 January 1835; Worcester Journal 15 January 1835.

[31] Worcester Journal 27 July 1837.