The Bedford election of 1830 provides an example of both riot and respectability [20-minute read]

Hotly contested elections in the long eighteenth century were public participatory events that were often turbulent, and occasionally violent. While the reasons for election riots varied widely, and the riots themselves frequently resulted in little more than torn clothing and bruised heads and knuckles, they could and did at times result in deaths. Perhaps the most egregious of these for our period was the riot at the end of the second day’s polling during the 1832 election at Sheffield. Crowd unrest, fueled by drink, began with an attack on a tavern serving as the committee room for one of the candidates, but then spread across the town, resulting in the reading of the Riot Act, and then, when that did not work, the calling in of the 18th regiment of Foot. The riot was only put down after the troops were ordered to fire on the rioters, causing five deaths and the serious injury of several others.[1]

Fortunately, most election riots were not that deadly and the speed with which civility might be restored, even after turbulent elections, could be striking. Violence at an election placed candidates and their supporters in difficult, and at times very vulnerable, situations, so the swift restoration of calm after an election was also a priority. The riot at Bedford, which took place at the hustings at the end of the second day of polling, and its aftermath in which order was swiftly re-imposed, provide a case in point.

Bedford in 1830 was a busy, growing market town and industries in straw plaiting and bobbin lace. It was a freeman and householder borough with about 1,100 qualified to vote. Although it had not been fully contested since 1790 and the Corporation was commonly understood to represent the interest of the duke of Bedford, it was not an easy borough to manage. It required regular attention and displays of emollient hospitality from the sitting members and their families. By 1830, there was genuine discontent among the electorate over the long-established Whig control of borough, where one seat was controlled by the Whitbreads (a rich London brewing family) and the other by the dukes of Bedford (the leading local landowners). The voters’ key grievance was with the Bedford interest, as the incumbent MP, Lord William Russell, had ignored the borough and — most specifically — had neglected to fulfil the socio-political responsibilities that sustained the family’s interest. His father, the duke, had chastised him repeatedly: not only had he only reluctantly attended the annual race meet for a day prior to the 1826 election, but he had also neglected to dine with the mayor the year before that, and had not even sent an excuse. To make matters worse, he had been guilty of ‘skipping the lace ball this year, which is a deep offence from the Member to the town (especially among the ladies) …’[2] Then, in 1828, he had left England to join his wife in Italy without attending the mayor’s feast, or sending an apology — or sending any game to the feast in lieu of his attendance. This was, according to his father:

… an unpardonable offence in the Eyes, and to the appetites of a ‘Corporation of Bedford’ whose love of good cheer is upon record. It is the universal Custom for the Members of a corporate town to attend the Mayor’s Feast, unless unavoidably prevented, and your colleague (though not the Corporation Member) came from a considerable distance to attend the dinner.[3]

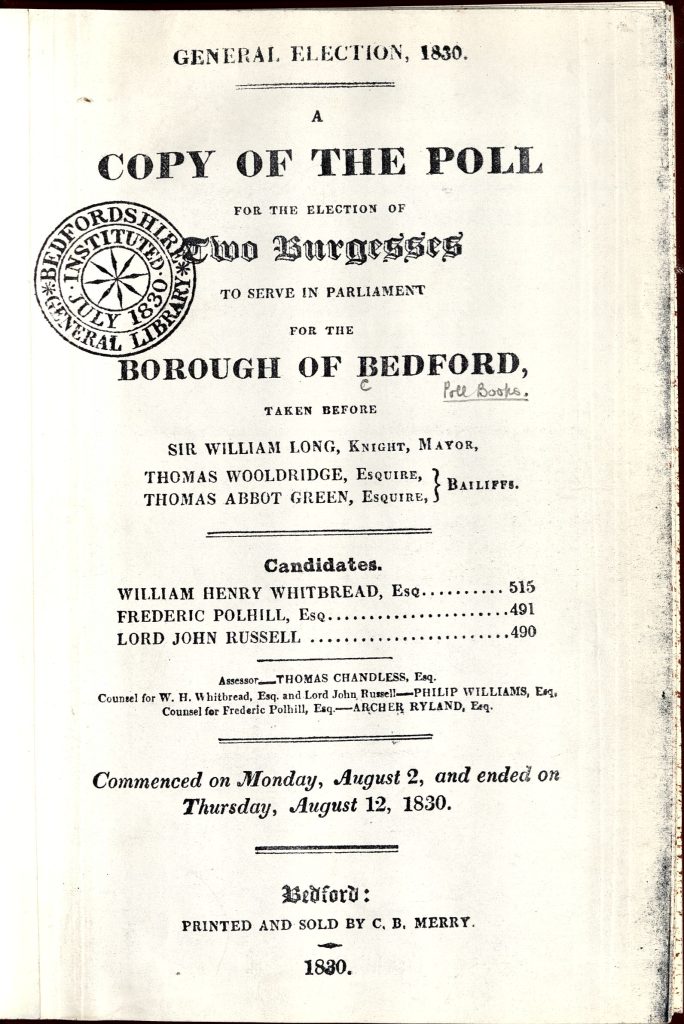

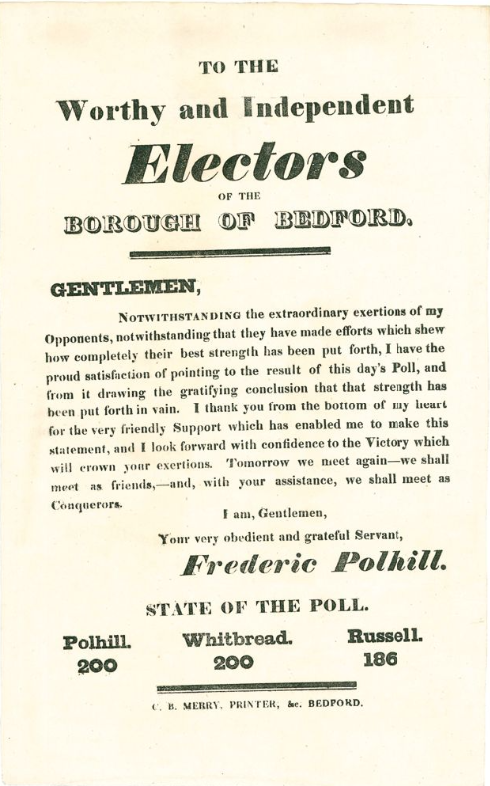

As a result, in 1830 the duke had preremporily decided that his younger son, the established and respected politician, Lord John Russell, would stand for the borough in place of his brother. Unfortunately for Lord John, the combination of his family connexion and the fact that he had openly supported Catholic Emancipation and published scathing remarks about Methodists made him immediately unpopular in a town that was both vehemently anti-Catholic and had a goodly number of Dissenters who were voters. When a Tory challenger emerged in the shape of the young wealthy landowner, Frederick Polhill, who took up the cry of ‘independence’, and was particularly active in canvassing and securing the support of the town’s artisans, tradesmen and lace-makers, the contest for the Russell seat was inevitable. In the end, Polhill would beat Russell by only one vote.

Polling lasted for the maximum allowable eight days (2–10 August) and was punctuated by drunkenness, brawling and vicious verbal exchanges. Supporters displayed their support for their candidates vocally, visually (by wearing ribbons or cockades in their candidate’s colour), and even materially, through the tools of their trade.

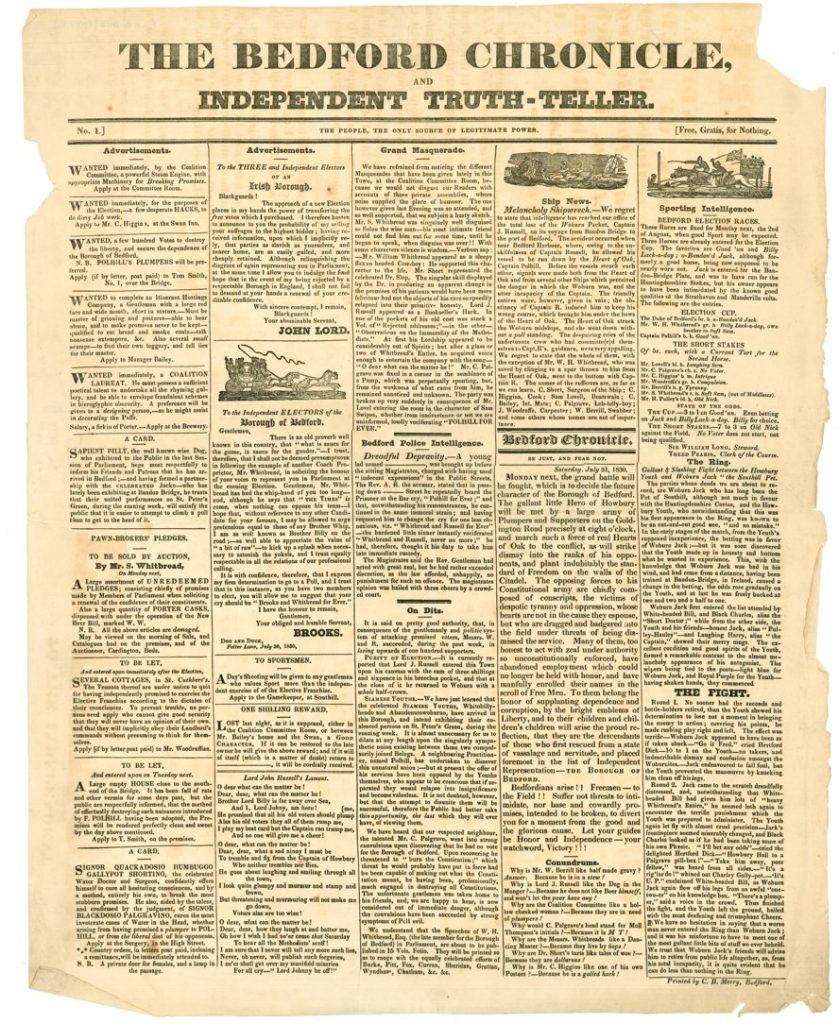

The election also generated a variety of genuine and mock publications.

Nearly 90 per cent of the votes were cast in the first two days — and the worst unrest took place at the hustings on St Peter’s Green at the end of the second day’s polling.[4] The crowds that typically gathered around the hustings, particularly at the end of a day’s polling, were distinctly heterogeneous, comprised of men, women and children, supporters of all candidates and none. In an electric atmosphere, with emotions heightened by the activities of the day and the rhetoric of the speakers, and made more febrile by alcohol, the possibility of riot was never far away. This was particularly the case as the hustings were a performative, even carnivalesque, space, where electoral rituals were enacted and where candidates were forced to interact directly with an irreverent, noisy, public. Hustings were usually sturdy, temporary wooden structures situated in a conveniently open, central, part of the town, often the market square. Stairs led to a raised and roofed platform on which the candidates, their political agents and/or key supporters gathered, as well as various election officials, such as the sheriff and under-sheriff (if there was one).

The hustings served as a stage for the announcement of voting totals and for the daily speeches by the candidates that were given at the close of every day’s poll. These speeches usually gave thanks to the voters for their votes and often made comments about the promise of votes or success to come in the next day (or days’) voting. They could be short and simple or long-winded; entertaining or informative. Candidates were expected, however, to show respect to their audience throughout (and to take their hats off when they addressed the crowd).

The riot at Bedford was precipitated by a speech at the end of the second day’s polling. According to custom, William Henry Whitbread, who was the candidate with the most votes, spoke first. In trying to criticise Frederick Polhill’s popularity, as Polhill was running a close second in the poll, Whitbread cast aspersions on the character of Polhill’s supporters. He claimed that while Polhill and his supporters talked ‘a vast deal about Independence’, the only claim most of his supporters had to to ‘independence,’ was being ‘independently drunk’.[5]

The response from the crowd was immediate — and angry:

The most tremendous uproar followed this declaration, and an immediate attempt was made to obtain summary redress. Loud cries of “Down with him,” and other fearful menaces proceeded from the crowd, the whole body of whom appeared at once to be propelled towards the hustings. The confusion was heightened by the endeavours of many of the most timid to make their escape. The women screamed, the boys scampered in all directions, the constables and stavesmen [special constables] gathered together in a solid square, for the protection of themselves and the speaker, who had called forth such a dangerous display of the public wrath.[6]

A full riot was only prevented by the fast action of Polhill, who managed to force his way to the front of the hustings and calm his supporters in the crowd. A temporary truce followed, but only lasted until the crowd realised that Whitbread’s and Russell’s horses had been brought to the rear of the hustings. Protected by a phalanx of between thirty and forty stavesmen, the two candidates managed to mount their horses. This made them visible to the crowd, however, which assumed they were going to flee the hustings and surged forward to stop them: ‘…all were encompassed in the midst of hundreds of the gallant Electors. A battle royal followed. The staves flew about the heads of the Independents; — the Candidates were speedily dismounted — Mr. Samuel Whitbread’s coat was torn every atom from his back, and part of the skirt affixed to a conquered constable’s staff, as the banner of the insulted party.’[7]

At this point, the violence could easily have increased and the riot could have spread to the town. Instead, Polhill and his friends once again managed to re-establish order. In a stroke of genius, they got his band to strike up the tune, ‘Oh! dear, what can the matter be’, and gave orders for Polhill’s supporters to form a procession. This gave Whitbread and Russell time to escape to one of the pubs friendly to their interest — escorted by 24 stavesmen and a hired London policeman. Polhill, accompanied by his band and friends, then marched his supporters — reportedly twelve abreast and upwards of a thousand strong — to their headquarters in the George Inn for more speeches, drinks and dinner.

Although the remainder of the poll was rough and tumble, there was no violence to echo this riot — even though the final outcome of the election was peculiarly dramatic. The poll closed at the end of the eighth day (10 August), with Whitbread in the lead at 513 votes, and Polhill and Russell only three votes apart, at 489 and 486, respectively. The focus of the election then moved to the Grand Jury room near the County Hall, where the Assessor, Thomas Chandless, Esq., of the Chancery Bar (and son-in-law of the mayor, Sir William Long),[8] had up to three days to scrutinize the election result and adjudicate upon the legality of those votes that had raised objections. Appearing in front of him were Philip Williams, Esq., who acted as legal counsel for Whitbread and Russell, and Archer Ryland, Esq., who represented Polhill.

In such a tight contest, validating even a few votes could easily have changed the outcome of the election. The theatre of the scrutiny, with its detailed legal debate about the nature of the franchise and the examination (and cross-examination) of questionable voters, was therefore played out in front of as many Bedford residents as could reasonably be crammed into the Grand Jury room. The key issue in almost all cases was whether the voter in question was an inhabitant householder not receiving alms, and thus qualified to vote in the borough.[9] Determining this was not entirely straightforward. Multiple residents of the local alms houses supported by Harpur’s Charity were doubly disqualified, for instance. Not only was the financial support that they received from the Charity for food and clothing deemed the equivalent of alms, but they were also categorized as ‘permissive occupiers’ rather than ‘inhabitant householders’ because they could be evicted from their homes by the Charity for bad behaviour.

In order to qualify as an inhabitant householder, the voter had to have ‘an exclusive right to the use of the outer door’.[10] Even living in a house with a front door, and possessing the key to that door, was not always enough to qualify, though. At least five voters — the resident surgeon at the Lunatic Asylum, the keeper of the Penitentiary, the turnkey of the Penitentiary, the keeper of the County Gaol, and the turnkey of the County Gaol (all of whom, interestingly, had voted for Whitbread and Russell) — were disqualified because they did not meet the criterion of exclusive access to their homes: all had houses that were parts of their respective institutions, and while they possessed keys to their outer doors, they were required to admit magistrates who demanded entry at any reasonable time.

A few votes, however, were allowed on the first day of the scrutiny and the gap between Polhill and Russell narrowed worryingly for the Polhill interest: Whitbread had gained one vote (514) and Polhill two (491), but Russell had gained three (489). With up to two more days of scrutiny ahead of them, Russell needed to secure only two more votes to tie with Polhill, and three to win. Unsurprisingly, the Assessor’s room was ‘crammed almost to suffocation’ on the morning of 12 August: ‘the most intense anxiety prevailed, as the cases referred were called on’.[11] Yet only one vote was proved over the course of the day — and that voter, despite having promised to vote for Polhill, split his vote between Whitbread and Russell. As no other votes were forthcoming, the Assessor closed his proceedings about 4 p.m. and proceeded to tally the final vote.

By 5 p.m., ‘it appeared as if every inhabitant of Bedford had assembled on the Green.’[12] Silence fell over the crowd around the hustings as the Assessor, the candidates, their legal counsel, and the three returning officers (the Mayor and two bailiffs), mounted the stage. The Mayor then read out the final vote: Whitbread, 515; Polhill, 491; and Russell, 490. The election of Polhill was met with such prolonged and jubilant cheering that all the subsequent speeches were drowned out.[13] At this point, with the difference between victory and defeat resting on only one vote, Lord John Russell and his supporters could easily have provoked another riot — but they did not. They accepted defeat, albeit sulkily. Instead, they supported their coalition candidate, Whitbread, who conducted an unobstructed, if rather short and muted chairing. In his letter of thanks to supporters published the following day, 13 August, Lord John adopted a tone of bitter disappointment and betrayal. After casting aspersions on the activities of the Mayor and Assessor in securing his defeat, and suggesting that Polhill’s victory ‘would disappear upon an accurate and regular investigation of the votes’, he closed his letter darkly by calling on the voters in the borough ‘to reflect, whether the rejection of my services, and the dissolution of an ancient connection, will be of any benefit to your local independence and prosperity, or to your general reputation and advantage.’[14]

The town, however, was not paying much attention; it was glorying in Polhill’s triumph. The contagion that had infected the hustings and caused affray and riot had dissipated. Polhill’s chairing, which began at 4 p.m. on the afternoon of 13 August, was colourful, partipicipatory, and peaceful — marked by the presence of well-dressed female supporters, a ‘merry peal’ of church bells, a tasteful and richly decorated chair, and a carefully ordered procession:

The streets were crowded to a degree that access became almost difficult. The windows of almost every house were thronged with elegantly dressed females, the greater portion of them clothed in dresses of purple, the colors of the triumphant member of the town. All were decked with cockades, and, if possible, an additional loveliness was excited in their appearance by the grateful smiles of approbation they so unsparingly bestowed. It was a sight for Britons to gaze on with feelings of pride and exultation. The bells of all the churches struck up simultaneously a merry peal; and precisely at four o’clock, the necessary arrangements being completed, the procession set out in the following order, from the George Inn:

500 Men on foot, eight abreast.

THE BAND.

TWENTY-FIVE SPLENDID COLORS, With Mottos suitable to the occasion.

CAPTAIN POLHILL

IN THE CHAIR,

Which was composed of the richest purple silk, with ornaments of gold, and profusely covered with rosettes of Bedford lace. The whole adorned with laurels, and tastefully placed upon a break.[15]

Nor did the celebration of Polhill’s victory end with the chairing. While it was customary for successful candidates to dine with their male supporters at an elaborate post-election dinner a few weeks after an election — and Polhill would do so with approximately three hundred of his supporters at the end of the first week of September — he made a specific point of honouring his female supporters first: ‘the electors of Bedford were too gallant to exclude the lovelier portion of it [creation] from their full share of enjoyment, at the result of a contest, to which their smiles and exertions and in no slight degree contributed.’ St Peter’s Green, which only three weeks earlier had been the scene of riot, became a site of genteel sociability, as Polhill and his supporters organised a tea party for the ladies, with a dance to follow. A band of musicians, accompanied by Polhill’s election banners, paraded through the town to invite the ladies to tea:

COME TO TEA!!

The Tea-Drinking

in honor of

Captain Polhill’s Election

will take place on St. Peter’s Green,

this afternoon, at four o’clock.

Ladies are requested to bring or send cups, saucers,

Tea-spoons, and tables.

A Band of Music will attend.

To conclude with a Dance.[16]

According to the report in The Englishman, the event was a great success: ‘nearly the whole expanse of St. Peter’s Green, in Bedford, was covered with tea tables, around which were seated at lesat 1,000 women. Their sweethearts and spouses (when obedient enough) were the attendants upon the happy guests.’[17] To emphasize the respectable sociability of the occasion, Mrs Polhill and her young children arrived about 5 p.m. and made their way around the tables. The evening ended convivially with country dances:

The whole of the arrangements were of the best order, nor do we ever remember witnessing a scene which appeared to afford more sincere delight to the many hundreds assembled on the occasion.[18]

Post-election harmony was restored.

[1] Sheffield Mercury, 15 Dec.1832.

[2] Letters to Lord G. William Russell from Various Writers, 1817-1845 (London, 1915), i. 130–2.

[3] Letters to Lord G. William Russell, ii. 154.

[4] By the end of the second day of the poll, the votes stood at Whitbread 442; Polhill, 423; and Russell 409: R. M. Muggeridge, A History of the Late Contest for the Representation of the Borough of Bedford (London: [1830]), 43.

[5] Muggeridge, 43–4.

[6] Muggeridge, 44.

[7] Muggeridge, 44.

[8] ‘Bedford’, in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1820-1832, ed. D.R. Fisher, 2009: https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/constituencies/bedford [accessed 1 Mar.2023].

[9] Muggeridge 70.

[10] Muggeridge 70.

[11] Muggeridge, 54.

[12] Muggeridge, 54.

[13] Muggeridge, 55.

[14] ‘Lord John Russell to the Independent Electors of the Borough of Bedford, Bedford, 13 Aug. 1830’, in Muggeridge, 59–60.

[15] Muggeridge, 56–7.

[16] Muggeridge, 77.

[17]The Englishman, Sunday, 5 Sept. 1830.

[18] Muggeridge, 78.