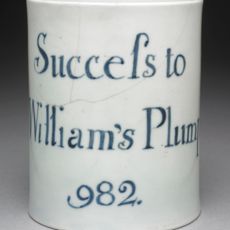

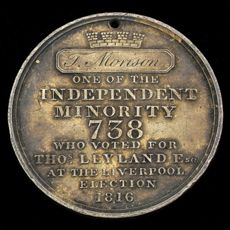

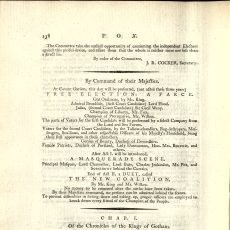

Liverpool expanded rapidly during the eighteenth century to become the second largest town and port in England. With access to the Mersey Estuary, merchants reaped huge profits from foreign trade in cargo, freight, and raw materials, as well as accounting for the country’s largest share in the trade of enslaved peoples. Industrial and commercial expansion was reflected in the development of the corporation-owned docks, and the construction of the Liverpool-Manchester Railway in 1830. Parliamentary elections were frequently contested and often raucous. They took place in the Exchange on the ground floor of the Town Hall until 1806–7, after which hustings were erected outside of the Hall. Voters were treated liberally (and sometimes outright bribed), while flags, ribbons, and musicians made them colourful and lively. By the nineteenth century, the electorate of c. 3,000 encompassed less than 4% of the town’s population, the majority of whom were shipwrights or men working in ancillary trades. According to Henry Peter Brougham, they were ‘chiefly the lowest and least worthy inhabitants’, and beholden to their masters so that only forty or fifty individuals determined the outcome of elections. This was no doubt an exaggeration; in reality, the electorate included various economic, social, political, and religious networks (including an influential and sizable dissenting minority).

The corporation held a powerful interest in Liverpool elections through its ability to disperse patronage, usually returning at least one member. It tended to align itself with the government: supporting the Walpole ministry in the early eighteenth century, and later becoming dominated by Anglicans and Tories after 1760, adopting the colour Blue. Its dominance gave rise to a persistent anti-corporation or independent party which was supported by nonconformists. During the turbulent 1790s (in the face of the French Revolution, foreign wars, and abolitionist movement) this independent faction fragmented. One group, led by Tory merchants like John Gladstone and John Bolton, adopted the colour Green and sponsored the likes of Banastre Tarleton and George Canning. The other group was a more reform-minded faction which included Whig and nonconformist families, and took on the colours Pink and White. Members of Parliament were carefully scrutinised by a buoyant local press and a merchant class who discussed politics at the Athenaeum library and gentlemen’s club. They were expected to promote the town’s commercial interests, resist the abolition of the slave trade, and manage the distribution of patronage.