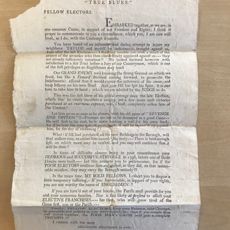

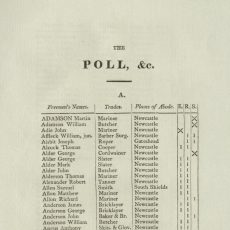

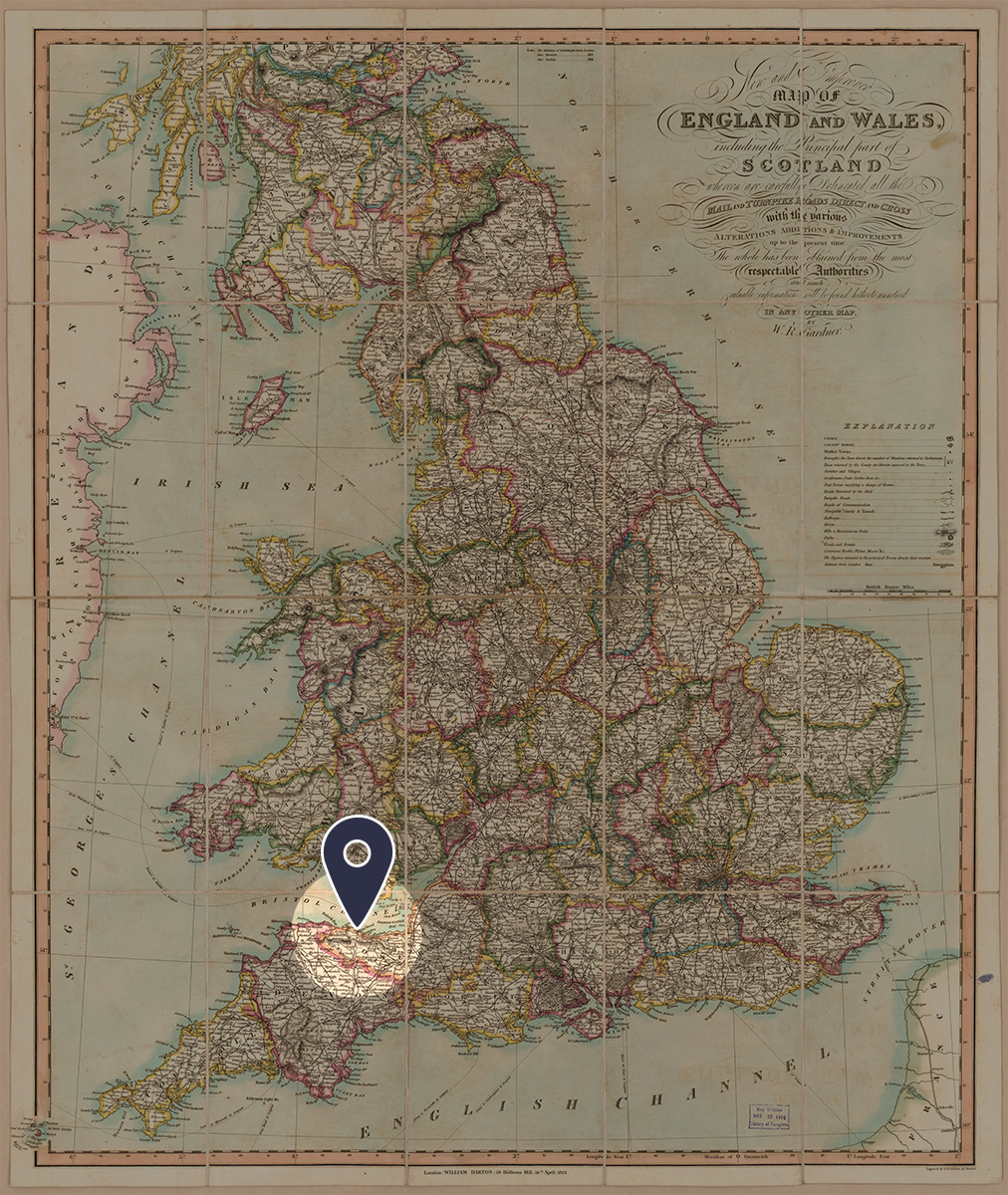

A small coastal market town on the Bristol Channel in Somerset, Minehead’s principal trades were in agriculture, fishing, and maritime trade. Over the course of the century, the port’s economic importance declined drastically from a centre of extensive foreign trade, to limited coastal trade. This decline corresponded with a general dilapidation in the town’s buildings – exacerbated by the ‘Great Fire’ of 1791. Minehead’s politics were dominated for most of the eighteenth century by the Luttrell family of nearby Dunster Castle. As lords of the manor, they had the right to appoint the two constables at an annual Court Leet who would serve as returning officers during parliamentary elections. The family consolidated their control of the borough by managing government patronage from the 1760s onwards, and by purchasing more property in 1803. One pamphlet even accused the Luttrells of deliberately engineering the town’s economic deterioration so as to cement their political control.

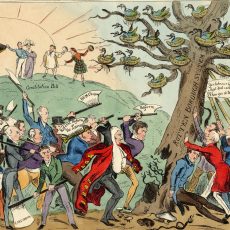

The Luttrell hold over the borough was not total, however. The Whitworths of Blackford and the Wyndhams of Kentsford and Cathanger also held electoral interests in the town. During the minority of Alexander Luttrell, 1711–26, a group of inhabitants organised opposition to the Dunster Castle interest. Moreover, a small but prosperous Quaker community spearheaded opposition to the Luttrells for much of the eighteenth century. In the 1760s and 1770s this was led by Robert Davis, described as the ‘long-headed Quaker’, and later by Captain William Davis, who was sued by the Luttrells for libel in 1804.[1] There were also prominent townsmen – referred to as ‘the Principal People’ – who would occasionally organise into the Bowling Green Club or Mrs. Ruth’s Club and lend their support to Luttrell or plot to bring in an external candidate. Treating and bribery were rife in Minehead. In 1747, Henry Fownes Luttrell was advised that ‘I find th[a]t the common fellows (who make full two Thirds of the Votes) are at pr[e]sent gapeing very wide for Money, & th[a]t nothing but money & a great deal of it, & Gold Too will satisfy th[e]m’.[2] The Luttrells therefore had to work hard to maintain their interest with constant cycles of dinners, entertainments, and treats at Dunster Castle, the Plume of Feathers, or one of the town’s other public inns.

[1] Somerset Heritage Centre, DD/L/1/59/7/13b: Rev. Leonard Herring to Henry Fownes Luttrell, 7 Oct. 1767; DD/L/1/60/16/6e: Public submission of William Davis and Robert Young, 4 Oct. 1804.

[2] Somerset Heritage Centre, DD/L/2/43/2/56: John St. Albyn to Henry Fownes Luttrell, 16 May 1747.

.jpg/square/230,230/0/default.jpg)