Why were poll books printed, and how were they used?

[10-minute read]

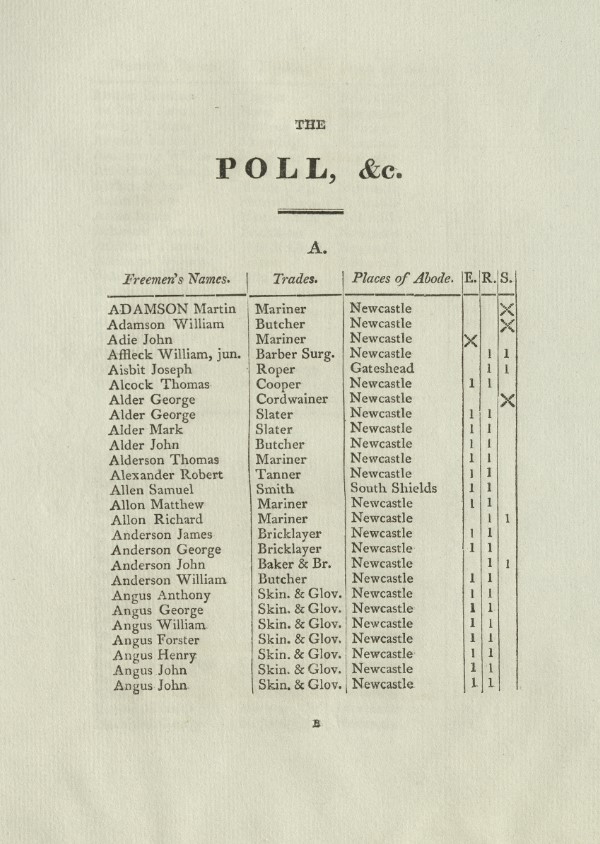

Poll books display huge variation in their form and format. Of the surviving poll books from the period 1695–1830, half are handwritten manuscripts, and were typically either compiled by clerks (or some other official) at the time of voting, or subsequently copied. The other half are printed poll books, which were usually produced by regional printers in search of profit. While it is easy to imagine why these documents were important for the candidates and other parties directly involved in an election campaign, it is more difficult to determine why commercially produced poll books may have appealed to the wider reading public. Some clues can, however, be derived from an examination of the typical content of poll books, as well as marginalia within surviving copies.

Partisanship

Many poll books had an overtly partisan function – whether commemorating and celebrating victorious candidates or highlighting a perceived injustice in the outcome. Some were produced on behalf of the victorious candidates (notably the Hertfordshire poll book of 1727).[1] Others only included the votes for particular candidates, or pairings of candidates. For example, the Bristol poll book of 1715 included only the votes for the Tory candidates, Philip Freke and Thomas Edwards, and was probably designed to draw attention to the fact that the Tories had not been returned despite receiving the most votes (due to the connivance of the Whig returning officers).[2] A poll book produced in the aftermath of the Liverpool 1734 election was even more explicit, when its editor claimed that their aim was to ‘shew the extraordinary Means whereby the Majority was Obtained’ for the Walpole candidates, and included a list of ministerial voters under the heading ‘OCCASIONAL TOOLS’ (i.e. implying that they had been created freemen for the express purpose of voting for the ministerial candidates).[3] Similarly, the Coventry poll book of 1780 includes a list of ‘Mushrooms’ who had ‘illegally’ voted.[4] It is important to remember, then, that poll books were not always impartial records of votes cast, but were compiled, edited, and framed by publishers who were sometimes active partisans. It is revealing that one unidentified individual altered the titlepage of A Correct Copy of the Poll (for the Coventry election of 1826) to read ‘An Incorrect Copy of the Poll’.[5]

During the course of the eighteenth century, it was increasingly common within the larger urban boroughs for rival printers to each publish their own edition of a poll book, suggesting the existence of a buoyant market for these texts. Sometimes publishers included prefatory material that clearly revealed the compiler’s allegiances. A poll book published by John Jones after the Coventry election of 1774 is prefaced by a highly partisan address in support of the independent candidates, Walter Waring and Edward Roe Yeo, alongside a stinging attack on a rival printer J. W. Piercy.[6] Six years earlier, Jones had included two large blank columns in a poll book, designed for a reader to:

make what private Remarks he pleases [about each voter]. It was in the Power of the Editor to have made many just, though severe, public remarks, against many of the Names, had not the Spirit of the Times, we now live in, rendered it dangerous even to tell Truth, lest it should be deemed a Libel.[7]

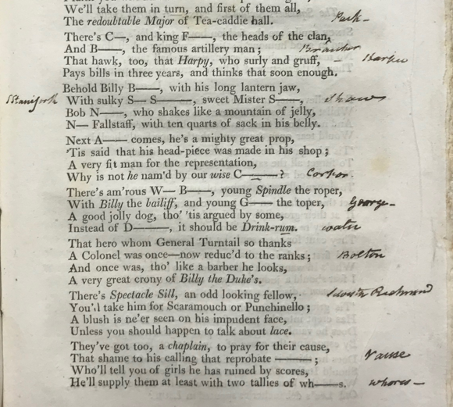

Ironically, of course, the same columns could have been used by corporation supporters to mock their opponents. Such paratexts simultaneously reflected and amplified partisan conflict in the constituency. The overt partisanship of these printed poll books suggests that they were targeting like-minded readers who would have purchased copies as an extension to the ‘print war’ that accompanied many urban elections.

Electioneering

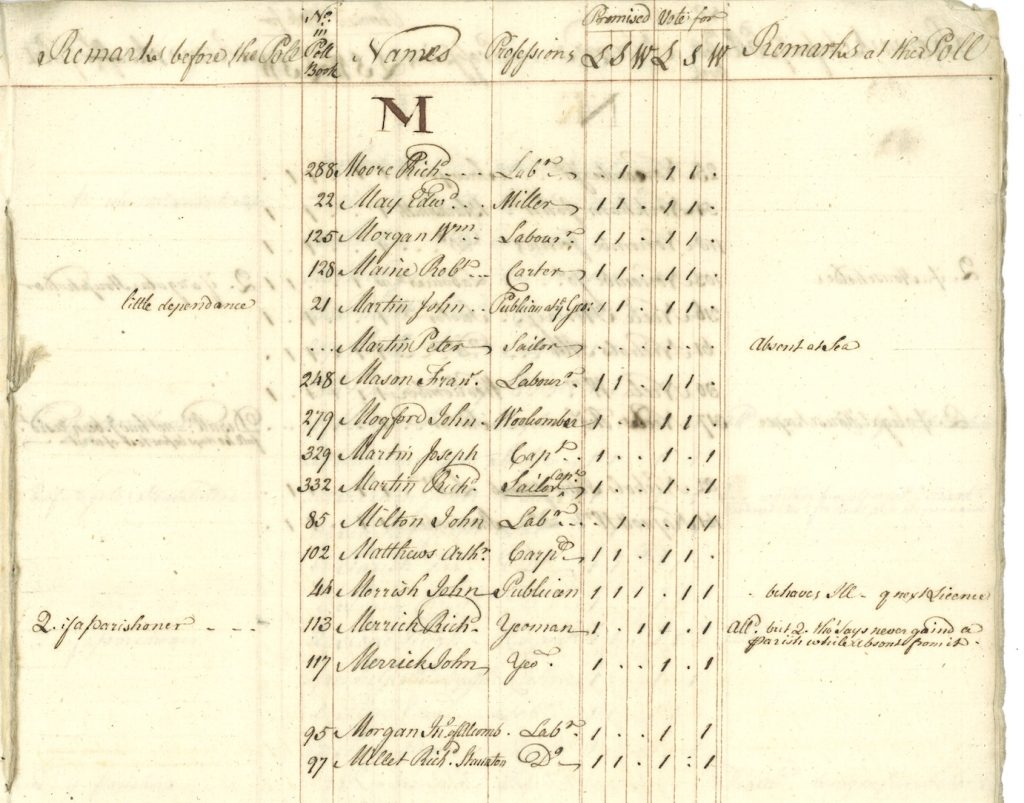

One potential market for printed poll books were the candidates, agents, and committee members who managed election campaigns. In the aftermath of an election, a printed catalogue of voters became particularly useful documents. They were essentially pro-forma lists of voters which could be annotated or used as canvassing books during a subsequent campaign. The Norwich poll of 1734 expressed hope that it would ‘be of great service both in taking and scrutinizing future polls’.[8] Annotations on surviving print and manuscript poll books clearly indicate that they were used for subsequent canvassing – marginal comments which range from ‘Dead’ to ‘East Indies’ to ‘Enlisted in Army’.[9] Some manuscript poll books were originally a candidate’s canvass book which were later used to record the poll. A Minehead poll for the 1768 election, for example, includes many ‘Remarks before the Poll’ or ‘Queries and Remarks at the Poll’ about voters (largely regarding their status as housekeepers or parishioners), but also more personal commentary, such as ‘a quibling fellow’ and ‘Saucey’.[10]

Poll books could also be valuable when preparing a petition to challenge the election result. A copy of the Bristol poll book of 1734 includes hundreds of manuscript annotations which were compiled in preparation for a petition on John Scrope’s behalf by the corporation against the return of Thomas Coster, on the grounds that he had been returned ‘by polling great numbers of persons who received alms and charities and others who had no right to vote’.[11] In total, 453 voters were marked as unqualified, with the stated reasons ranging from them being a ‘Roman Catholick’ to having being ‘burnt in the hand for rob[b]ing Jonathan King Esq’.[12] This petition was ultimately abandoned. The staggeringly corrupt Liverpool by-election of 1830 led to widespread allegations of bribery, and a subsequent trial appears to have been the reason why two copies of a poll book for the election (held at the British Library and Liverpool Archives) contain annotations detailing more than £22,000 worth of bribes (via payments of between £5 and £40).[13] The election was eventually declared void.

Ownership

It is very difficult to know how many copies of a single poll book were printed, let alone who purchased them or what they did with them. However, in a rare instance, the poll book for the Kent election of 1734 was funded by a subscription campaign, making it possible to discern something of its readership. The 271 subscribers were composed of gentlemen, clergymen, and prosperous middling sorts, and were not limited to voters for a single pair of candidates. Some subscribed for multiple copies, suggesting a print run of around 300. Two of the candidates from opposing sides, Sir Edward Dering and Sir George Oxenden, subscribed for ten and four copies each (respectively), but it is unclear whether these were simply mementos or obtained in preparation for a potential future canvass.[14]

Those who purchased copes of printed poll books may have been voters who simply wanted the novelty of seeing their names in print (and possibly listed alongside various notable or fashionable figures). A copy of the 1761 poll book for Liverpool has the name ‘James Sudell’ inscribed on the title page, who duly appears on page 52 as voting for Sir William Meredith, the anti-corporation candidate.[15] Of course, as an attorney, there are many other reasons why Sudell may have had need of voting records. Other readers may have held a genuine interest in local politics, or had a different use for the polling lists. Two Liverpool poll books for the elections of 1796 and 1802 are inscribed with the name ‘Robert Rolison’, whose will of 1808 described him as a ‘gentleman of Liverpool’.[16] Yet he never appears as a voter himself. It is possible that Rolison was not a freeman of the town, and therefore ineligible to vote, but nonetheless remained an interested observer of Liverpool’s electoral politics. Other readers used the poll book both as a remembrance of the election, and to record their own feelings on the outcome. A copy of the poll for the 1790 Cambridge University election, owned by the clergyman and theatre historian John Genest, was annotated with his own Latin quotations. Genest had entered Trinity College ten years previously and appears within the poll book as plumping for the losing candidate, Lawrence Dundas; at the end of the volume he has inscribed a quotation from Seneca, ‘Non tam bene cum rebus humanis agitur, ut meliora pluribus placeant’ (Human affairs are not so happily arranged that the best things please the most men).[17]

Some poll books were packaged with other election literature, including narratives of the contest, speeches and addresses by the candidates, and collections of songs, squibs, and other cheap print produced during the campaign – providing what one editor called an ‘account of the Electioneering Paper War’.[18] It may have been this additional material which fuelled sales, more so than the poll records themselves. One copy of A Compendious and Impartial Account of the Election (of 1806 in Liverpool) includes numerous contemporary manuscript additions where a reader has attempted to identify all of the implied or blanked-out references to local figures.[19] When we turn to the poll itself, the majority of its pages have been left uncut (as they would have been when it was collected from the printer) and are therefore unreadable. Another standalone poll book for the Liverpool election of 1812, which does not include any additional material, similarly reveals that some pages were left uncut.[20] It implies that their original owners had dipped into the poll book, perhaps to look up specific people, and ignored the remainder. That is not to say that such practices were the norm: in other surviving poll books contemporary readers have gone through the entire volume and carefully corrected the text according to the printed errata, suggesting a different (and perhaps less functional) relationship with the text. For many, the ownership of poll books may have fed into a larger eighteenth-century phenomenon of gathering and archiving electoral materials (including other forms of election literature and material culture) as keepsakes for private albums and collections.

For the modern historian, polls books can clearly serve as more than just a simple list of voters to be stripped for data about electorates and voting patterns. Beyond the matter of ‘votes cast’, they can tell us a huge amount about how these elections were fought, and how people engaged with them – both prior to an election, and after a campaign had concluded. These documents should be positioned within the vast array of print and manuscript literature that was typically produced during an eighteenth-century election campaign, and regarded as part of the rich material culture of elections.

[1] John Cannon, ‘Poll Books’, History, 47 (1962), 167.

[2] A true and exact list of the inhabitants… who poll’d for Philip Freke and Thomas Edwards… (Bristol: W. Bonny, 1715).

[3] An exact list of the persons who polled… (n.p., [1734]), 1, 11.

[4] A correct copy of the poll… (Coventry: R. Bird, [1780]), 104–7.

[5] Coventry Central Library, A correct copy of the poll… (Coventry: Merridew and son, 1826), sig. A1r.

[6] A complete copy of the poll… (Coventry: J. Jones, [1774]), i–iii.

[7] A correct copy of the poll… (London: J. Jones, [1768]), iii.

[8] Quoted in Cannon, ‘Poll Books’, 166.

[9] See, for example, Coventry Central Library, A correct copy of the poll… (Coventry: R. Bird, [1780]).

[10] Somerset Heritage Centre, DD/L/1/59/8/9: Minehead poll book, 18 Mar. 1768.

[11] CJ, xxii, 333.

[12] British Library, General Reference Collection 291.b.24: An alphabetical list of the freeholders… (London, 1734).

[13] British Library, General Reference Collection 10349.e.11.(10.): The poll for the election… (Liverpool: J. Gore, 1830); Liverpool Archives, 324.242 PAR: The poll for the election… (Liverpool: J. Gore, 1830).

[14] The poll for knights of the shire to represent the county of Kent… (London: printed for Stephen Austen, 1734), sigs. A3r–A5r.

[15] Liverpool Archives, 324.242 PAR: An alphabetical list of the free burgesses who polled… (Liverpool: R. Williamson, 1761).

[16] Liverpool Archives, 324.242 PAR: The poll for the election… (Liverpool: H. Hodgson, [1796]); Liverpool Archives, 324.242 PAR: The poll for the election… (Liverpool: Ferguson, Mackey, 1802); The Record Society for the Publication of Original Documents relating to Lancashire and Cheshire, 63 (1912), 75.

[17] British Library, General Reference Collection DRT Digital Store RB.23.a.8527: The poll for the election… by John Beverley (Cambridge: John Archdeacon, [1790]), 37.

[18] A complete list of the 1425 burgesses… (Liverpool: W. Jones, 1802), 1.

[19] Liverpool Archives, 942 HOL/26: A compendious and impartial account of the election… (Liverpool: Wright & Cruickshank, [1806]).

[20] Liverpool Archives, 942 HOL/27: The poll for the election… (Liverpool: J. Gore, [1812]).