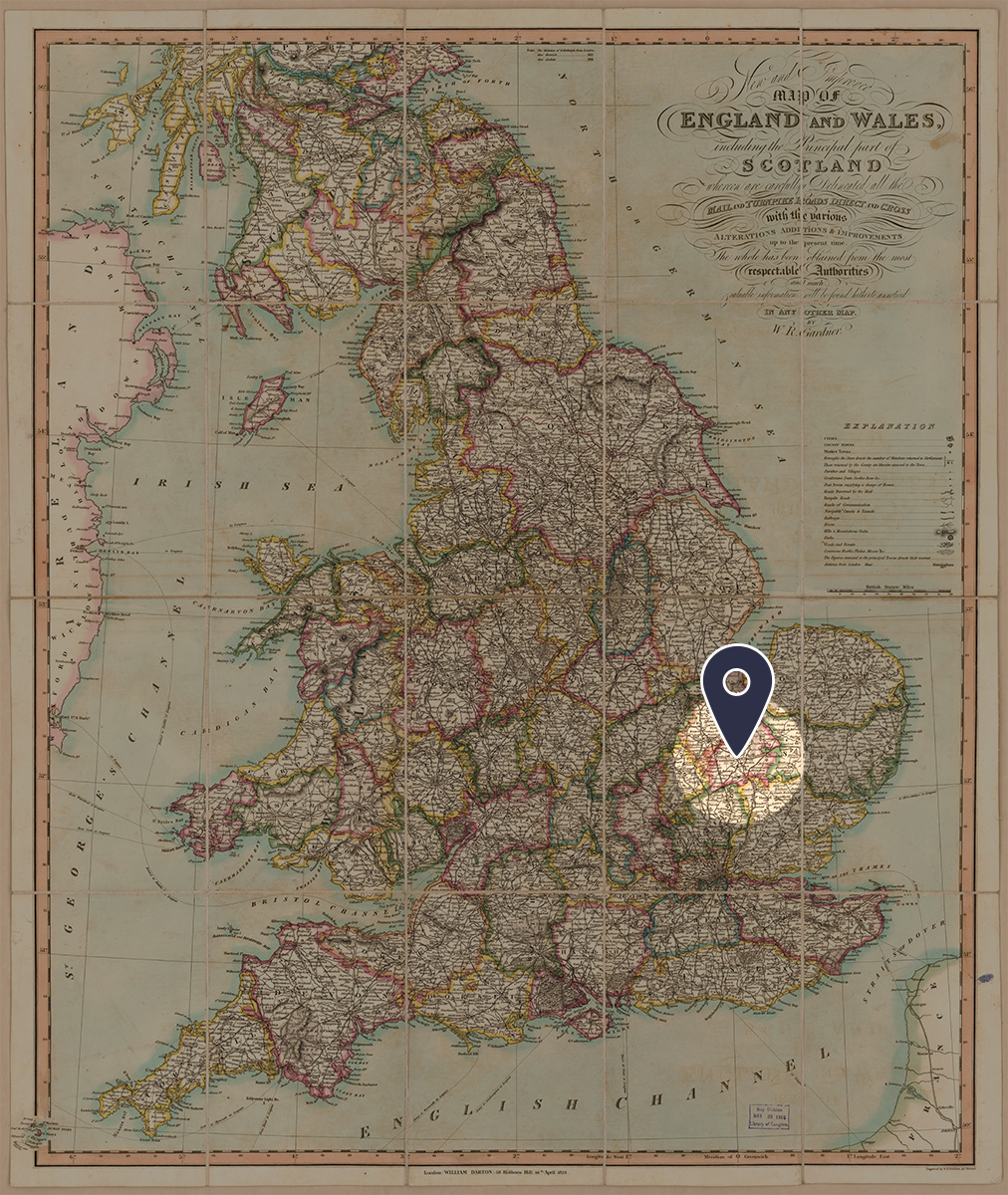

The University of Cambridge was a unique constituency, as its voterate was confined to the male graduates, doctors and masters of arts of the university’s colleges, rather than a geographic area. Over the course of the eighteenth century, the number of voters grew from 193 in 1692 to 1450 men in 1831. Votes were recorded in the university’s poll books according to college affiliation. St John’s, King’s, and Trinity Colleges were seen as some of the most powerful. Together, they formed over half of the voting population. As the electorate of Cambridge University was composed of the university’s Senate, the chancellor of the university had a strong interest during elections in the eighteenth century. Over the course of the eighteenth century, the chancellors included the dukes of Somerset (1689-1748), Newcastle (1748-1768), Grafton (1768-1811), and Gloucester and Edinburgh (1811-1834), meaning that their political outlook and candidates tended to sway the politics of the university.

Due to the changing interests of the chancellors, the University of Cambridge shifted between Whig and Tory allegiance. From the 1690s to 1727, the university was a Tory stronghold, and regained this status with William Pitt’s tenure as MP. Notable MPs for the constituency included the mathematician Isaac Newton, William Pitt the Younger (who served as Prime Minister from 1783 to 1806), Lord Euston (later the 4th duke of Grafton), and Viscount Palmerston (future Prime Minister in the 1850s and 1860s). The University of Cambridge (like the University of Oxford) elected two Members to the House of Commons from 1603. Over the nineteenth century, ten other universities were given constituency status until university constituencies were abolished with the Representation of the People Act 1948.