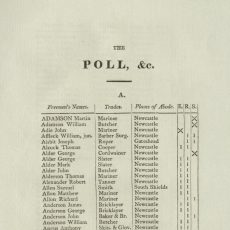

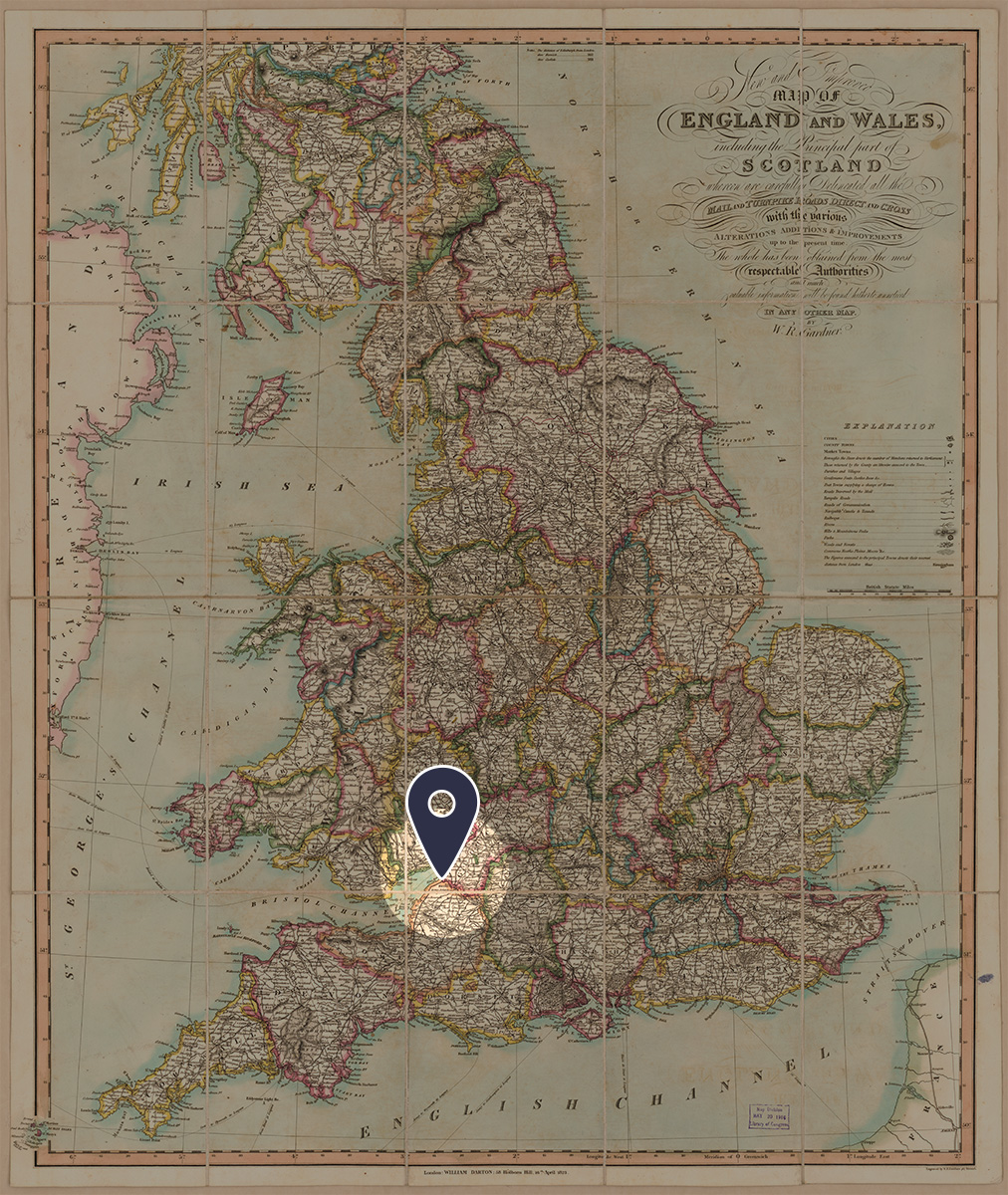

For much of the eighteenth century, Bristol was England’s second largest city. Its prosperity was based on international commerce, including the transatlantic trade in enslaved people, the sugar and tobacco industries, manufacturing, and banking. This only began to decline at the end of the century with the emergence of other industrial centres, notably Liverpool. Bristol’s population grew from about 20,000 in 1700 to 65,000 in 1800, and its relatively open franchise meant that it had the largest urban electorate outside London. In 1700, around 3,500 freemen were entitled to vote in parliamentary elections; by 1830, over 6,000 were voting: about a quarter of adult males. Many of those eligible to vote lived outside the constituency. A significant minority of them were Dissenters.

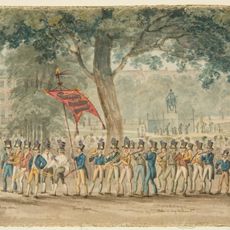

Bristol elections were renowned for their rowdiness and expense. ‘Polling money’ was routinely paid to voters, election rituals were often elaborate and highly participatory, an active local press printed politicised newspapers and handbills, and violence often ensued, including window-smashing, occasional pitched battles, and hired bands of ‘bludgeon men’. Electoral festivity was regarded almost as the constituents’ right. In 1826, one pamphlet, signed by ‘A Journeyman Cooper’, complained bitterly that ‘we are to have no supper tickets! no ribbons! and even no chairing!’ A procession following the 1831 election drew a crowd estimated at 10,000.

In such a large constituency, political clubs developed to manage elections. The Steadfast Club (later the White Lion Club) organised the Tory interest, and was matched by the Whig Union Club. These two factions – Tories and Whigs, or Blues and Yellows – dominated for most of the century. The city’s mercantile governing elite generally supported the Whigs. A pronounced anti-Catholicism permeated Bristol politics, which Tory candidates were able to exploit. The result was a fairly even balance between Whigs and Tories. The sheer expense of any election was a recommendation to compromise, and a contest was often avoided by agreeing to share representation between the two parties. That said, tempers could flare even when there was no contest. In 1807 the two sitting Members were declared as re-elected, but when one of them was chaired, he was attacked, and the military had to be called in to restore order.

Later in the century, the clear-cut Whig-Tory divide began to fray. The election of 1774 was highly contested, hugely expensive, and based on new alliances. Edmund Burke, then known chiefly as a writer, philosopher and political reformer, was nominated only after the poll had begun but was comfortably elected. His Speech to the Electors of Bristol at the Conclusion of the Poll famously set out the principle that MPs should not be merely delegates of those how had elected them but should act in Parliament for the good of the nation as they saw it. His brand of aristocratic Whiggism was not popular in Bristol however, and he was forced to withdraw from the next contest in 1780. By the early nineteenth century new political factions were being managed by a Whiggish Independent and Constitutional Club and, on the ministerial side, the Loyal and Constitutional Club. A Bristol Concentric Society was established in 1819 to further civil and religious liberty and parliamentary reform. True to form though, the 1830 election was characterised by ‘shameful outrages’: armed mobs fighting each other, an intense paper war (including the complete covering of the town’s statue of William III – and horse – with printed handbills), as well as a physical attack on one of the candidates while he was addressing a crowd.

.jpg/square/230,230/0/default.jpg)