Following an election, collections of printed ephemera were sometimes published [20-minute read]

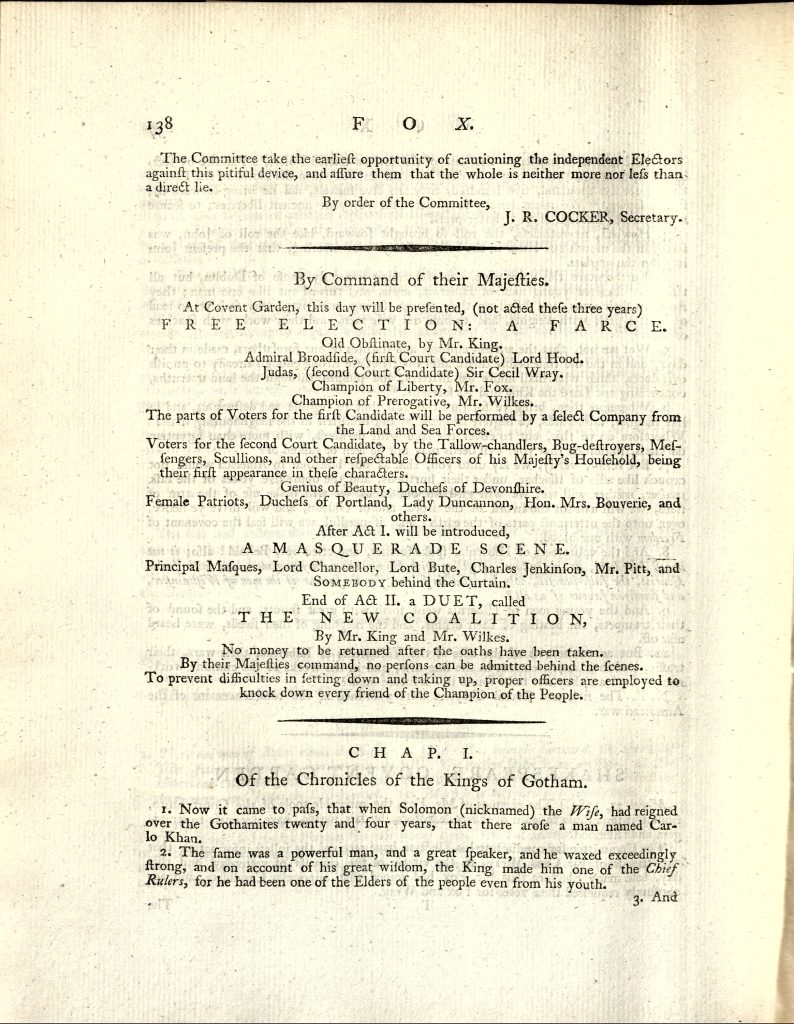

These compendia might contain handbills, songs, visual prints, advertisements and addresses that had been published as part of the campaign. Such volumes have come to be known as ‘squib books’. A ‘squib’ is a short piece of satirical writing, generally taking the form of a song or poem, a mock advertisement, or even a parody of the bible or a burlesque catechism. The books often trace the course of an election, beginning with the nomination correspondence and candidates’ addresses and progressing through the daily polls to the election result. They may also include an account of any subsequent challenge or scrutiny.

This squib book from the 1820 Newcastle election, housed in the Newcastle University Library, collected election handbills, newspaper clippings, and other ephemera like candidates’ ribbon favours (p. 170).

Generally, squib books present themselves as disinterested historical records of an electoral contest, preserving material that would otherwise have been thrown away. They perform a kind of self-conscious archiving, assembling miscellaneous items in a printed volume in a way that replicates what an individual might formerly have done to collect and preserve electoral ephemera (and indeed, such private electoral scrapbooks do exist). Squib books seem intended to provide anyone in the constituency with a definitive history of the election, perhaps appealing chiefly to local interest, but also available to anyone living further afield who might not have been able to participate directly in the election but who was nevertheless interested in how it played out. As the publisher of one of the two contending squib books published after the fiercely fought Essex county election of 1830 commented, the ‘singular’ nature of the contest had given an ‘extraordinary and permanent interest to the Proceedings’. The publication was intended not only to record for posterity ‘the talent displayed on each side’, but also to go beyond a mere ‘Historical Production’ to preserve ‘the grace and vivacity of the humourist’:

The varieties of Wit and Humour here presented, will, now that the excitation which prevailed at the time of their first appearance has subsided, be read with pleasure in many instances by those whom they were expected to annoy. The jest survives, though the venom is no more….

Essex Election, August 1830 (Chelmsford: Stationer’s Hall Court, 1830), viii.

Some squib books were cheaply printed and were ostensibly designed to have had a wide circulation. The New Election Budget collecting material from the 1784 Norwich election was apparently published actually as the contest progressed in 25 short parts, each three pages long, with ‘One-half of the Money arising from the Sale’ split between ‘the Society for recovering Persons Apparently Drowned’ and ‘the Society for releasing Persons confined in Gaol for Small Debts’. Others were major publications, such as James Hartley’s History of the Westminster Election, containing Every Material Occurrence (1784), which ran to over 500 pages, reproduced numerous fold-out prints, and sold at the enormous price of 10s. 6d.

Even if their seeming purpose was to collect and record the printing thrown up by an election, it is not completely clear what function squib books had in electoral culture. They are often surprisingly cheery in tone, as if the publishers were chiefly celebrating the vibrancy of the election, and were proud of the creativity that had gone into the literary elements of the campaign. A 1784 squib book for Norwich and Norfolk, for instance, is entitled The Election Magazine; or, Repository of Wit and Politics, and purports to be an ‘impartial collection of the essays, strictures, squibs, songs, prophecies, queries, epigrams’ and so on that were distributed during the canvass and campaign. Squib books can also seem like a celebration and memorialisation of a constituency’s political engagement and maturity, an expression of how civic duty had been performed, and how, even after the most violently fought election, the community could come together and reflect in equanimity on what had passed. The squib book was both a genre which was copied for other political uses, as well as its own form which preserved an election’s printed ephemera. But even though squib books generally claimed ‘utmost impartiality’ in presenting electoral material from all factions, an analysis of the publishers, editors, and booksellers reveals that this was not always the case.

This display of allegiance to a political faction or campaign is particularly noticeable in Westminster. The Authentic Narrative of the Events of the Westminster Election was published in 1819 following the contested by-election for the borough between George Lamb (Whig), John Cam Hobhouse (Whig turned Radical), and John Cartwright (Radical). Over the course of polling, numerous voters were turned away from casting their votes because, it was claimed, they had not paid their rates. Since rate collectors (employed by wealthy Whigs) served as poll clerks, they were in a position to recognise those who had paid and those who had not. Francis Place argued that Hobhouse lost 1200 votes as a result of the rate collectors’ presence. The by-election returned George Lamb as MP. Despite his majority in the poll, a mob attacked his committee rooms at the close of the election, forcing him to flee and hide from the angry rioters.[1] A petition was submitted against Lamb’s return but dropped due to the financial costs. In an effort to be seen as impartial, the Authentic Narrative presented the squibs and advertisements from both Hobhouse’s and Lamb’s campaigns. Lamb’s speeches and squibs were ‘given from the Morning Chronicle, which’, the editors of the squib book noted, ‘we presume to be the fairest mode proceeding which we could adopt’.[2] Meanwhile, permission to reproduce Hobhouse’s speeches were granted by the candidate himself. Wishing to present a ‘simple narrative of facts’, Hobhouse’s election committee sought to frame the squib book as a purveyor of clear-cut facts, cutting through the emotional discourse elicited by the propaganda of the campaign. Yet despite the claim of impartiality, the Authentic Narrative was ‘compiled by order of the committee appointed to manage the election of Mr Hobhouse’ to demonstrate that Mr Lamb was not the reformer he claimed to be, and that it was the Whigs who hired ‘bludgeon-men’ and ‘horsemen’ to kick up the angry mob at the close of the election.[3] Dedicated ‘to the friends of radical reform’, the squib book positioned Hobhouse as the radical candidate who truly represented the people, critiquing ‘the proprietors of the Journals… and the gross violation of all truth by the Whig conductors of the Morning Chronicle’ for swaying voters to the cause of the Whig candidate, George Lamb.

Electoral advertisements might be seen as propaganda for one candidate or another, but the publication of squib books reveals that they were important to preserve as an expression of civil and civic duty. Collecting the masses of printed ephemera like handbills and newspaper advertisements was a significant undertaking, but often made easier through the connection between newspapers and the printers of squib books. The second of the two contending squib books for Essex in 1830 — Essex County Election: Report of the speeches delivered at the hustings — was printed and sold by Meggy and Chalk. As proprietors of both the Chelmsford Chronicle and Essex Herald, Meggy and Chalk were well placed to preserve the advertisements for future readers. So, too, was William Pine (printer of the Bristol Gazette from 1767), who was responsible for publishing The Bristol Contest; the proceedings at the contested election in 1781.[4] In Bedford, The History of the late contest for the representation of the Borough of Bedford, published in 1831, was collected and published by R.M. Muggeridge, editor of the Herts and Bedfordshire Mercury.[5] It was sold by Clarke Barber Merry in Bedford, who was known for printing election pieces for local politicians, as well as the fashionable loyal and conservative bookshop, Hatchards, in Piccadilly, suggesting a wider interest and readership than Bedfordshire locals.

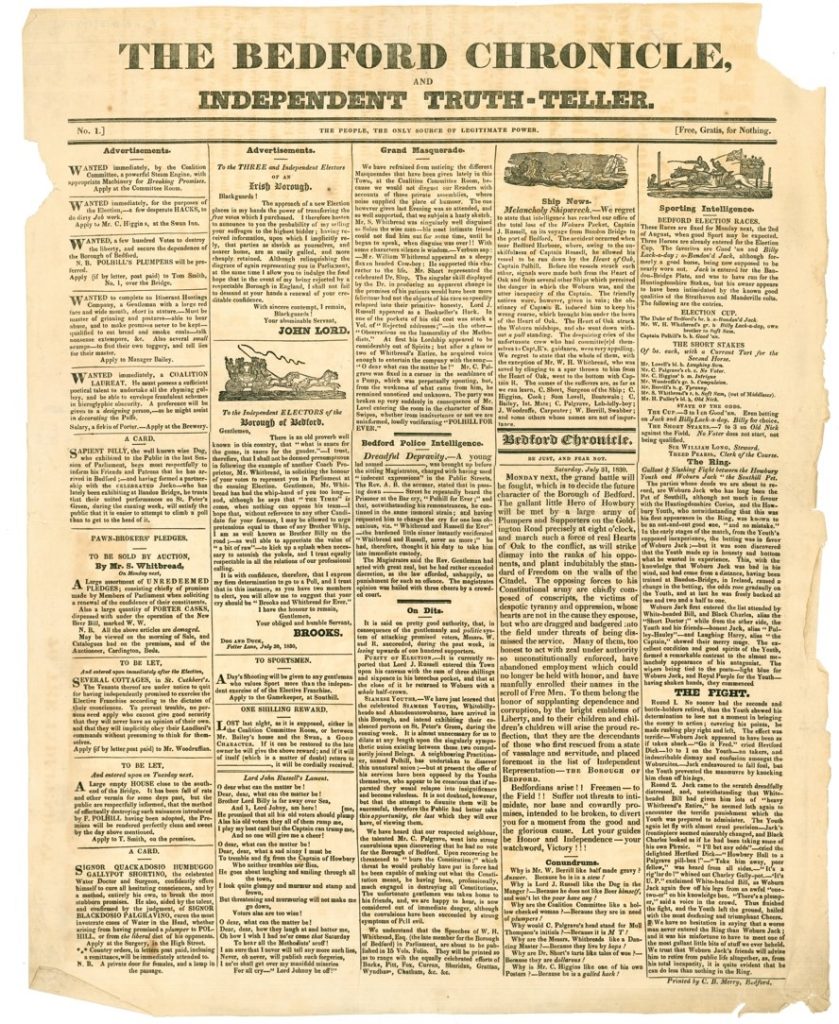

Of course, newspaper proprietors frequently took sides in any election, so it is no surprise that when they published squib books, they continued to lean towards their favoured candidates. It is even occasionally possible to determine how the printer or bookseller of the squib book voted during the election. In the closely contested election in Bedford in 1830, Clarke Barber Merry was listed in the poll book as voting for Frederick Polhill, the independent candidate contesting the Whitbread and Russell interests in the borough. During the election, Merry had been actively involved in printing several of Frederick Polhill’s addresses to the voters and the squib newspaper, ‘The Bedford Chronicle and Independent Truth Teller’.[6] The close result of the poll (Whitbread 515, Polhill 491, Russell 490) led to a scrutiny, but the result of the 1830 election was upheld. Similarly, during the contested by-election in Bristol in 1781, the printer William Pine is recorded as voting for the losing Tory candidate, Henry Cruger. It is therefore not surprising that The Bristol Contest, which Pine published in 1781, took Cruger’s side. Cruger lost, but the squib book, if it did not exactly rewrite history, presented the election as a heroic defeat, in which Cruger’s supporters had done all they could: ‘So earnest did [his supporters] appear in the cause of Mr. Cruger that above a thousand of them subscribed their names to vote for him. They also sent a deputation to the Union Club, requesting them to unite in support of the Whig interest in the person of Mr. Cruger.’[7]

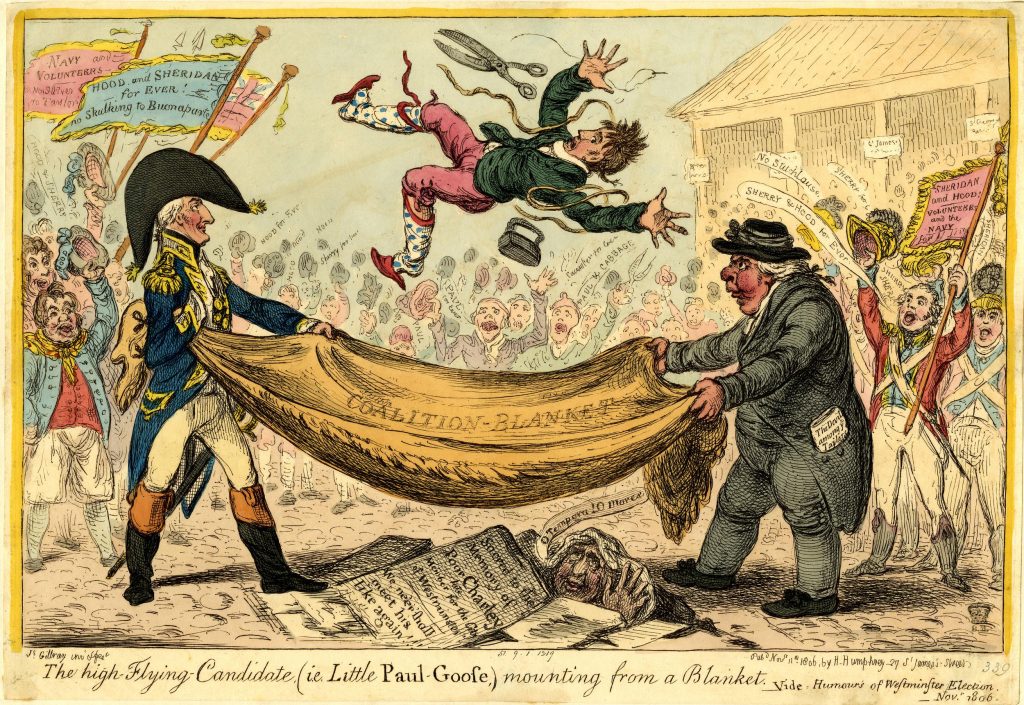

The London publishers were similarly politicised. Hartley’s History of the Westminster election from 1784 was ‘printed for the editors’ but ‘sold by J. Debrett, opposite Burlington House, Piccadilly’.[8] Located directly across the street from the duke and duchess of Portland (a key Whig family) at Burlington House, John Debrett’s business took over from John Almon, a journalist who published reports on debates in the Houses of Parliament and frequently published for John Wilkes and American republicans.[9] Debrett’s shop was frequented by fashionable Foxite Whigs in London and faced direct competition from John Stockdale, who had worked as a porter for John Almon. Stockdale’s rival shop two doors down from Debrett was consequently patronised by Pittites.[10] Twenty-two years later, the 1806 History of the Westminster and Middlesex Elections was printed for J. Budd at the Crown and Mitre in Pall Mall, R. Bagshaw in Brydges Street in Covent Garden, and Hannah Humphrey in St James’s Street.[11] Mr Budd’s connection to this squib book is particularly interesting as he was known as ‘Bookseller to H.R.H. the Prince of Wales’.[12] Hannah Humphrey’s presence as a seller of the 1806 squib book is also interesting as she primarily sold prints and caricatures. The elderly Hannah Humphrey exclusively sold James Gillray’s political caricatures and was the caricaturist’s friend and landlady from 1794 until his death in 1815.[13] She would have been particularly active with the 1806 Westminster election as Gillray produced numerous caricatures over the course of that contest. The 1806 squib book would consequently have made a fitting companion publication alongside the election caricatures.

Examining the publication history of squib books opens up close connections between election committees, printers, and booksellers, revealing a network of professionals and politicians crafting and circulating retrospective election narratives. Squib books are also a vital source for studying eighteenth-century electoral history, collating printed ephemera like handbills, squibs, and advertisements together in a bound volume for future readers. Newspapers, on the other hand, were often recycled or repurposed as wrapping paper, and insulation, becoming a much more ephemeral source at the time. Without the squib books, many of these sources might not have survived at all. Although a prime avenue for printers and booksellers to generate additional revenue after an election, the publication of squib books also shows a mark of respect for the electoral process, preserving the temporary flurry of electoral activity within its pages for posterity.

[1] Grey mss, Lambton to Grey mss, Lambton to Grey [18 February 1819]; Chatsworth House, Chatsworth mss, Lady Morpeth to Devonshire, 4 March 1819.

[2] An Authentic Narrative of the Events of the Westminster Election (London, 1819), 2.

[3] Authentic Narrative, 1, 400.

[4] A.P. Woolrich, Printing in Bristol (Bristol, 1986), 5.

[5] R.M. Muggeridge, A History of the Late Contest for the Representation of the Borough of Bedford (Bedford, 1831).

[6] Bedfordshire Archives, Squib ‘The Bedford Chronicle and independent truth teller’, printed by C.B. Merry, Bedfordshire Archives BorBG10/1/27; ‘Address by Frederic Polhill to the electors of the Borough of Bedford thanking them for electing him as their representative in parliament. Includes the results of the poll’, Z1112/1.

[7] The Bristol contest; the proceedings at the contested election (Bristol, 1781), 7.

[8] James Hartley, History of the Westminster Election (London, 1784).

[9] David Fallon, ‘Piccadilly Booksellers and Conservative Sociability’, in Sociable Places: Locating Culture in Romantic-Period Britain, ed. by Kevin Gilmartin (Cambridge University Press, 2017), 72.

[10] Sylvanus Urban, The Gentleman’s Magazine (London, 1846), clxxx, 603.

[11] History of the Westminster and Middlesex Elections, titlepage.

[12] Richard Brinsley Sheridan, A Comparative Statement of the two Bills for the better government of the British Possessions in India (London, 1806).

[13] Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850, ed. by Christopher Murray (London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2004), 422.