Slavery and abolition could be contentious platform issues in 18th-century England [15-minute read]

Understandings of Slavery

In eighteenth-century political discourse, ‘slavery’ was a potent but often imprecise term, used across the century to describe many kinds of personal, political or religious oppression rather than specifically the ownership of people as property, as we now generally understand it. For instance, some, writing or demonstrating in opposition to greater civil rights for Roman Catholics, claimed that Catholicism imposed a kind of ‘slavery’, which needed to be resisted. Others, such as the feminists Mary Astell and Mary Wollstonecraft, described the position of women and the institution of marriage in eighteenth-century Britain as forms of ‘slavery’.[1] When we find ‘slavery’ used as political slogan, even during the era of the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade, it frequently refers to perceived attacks on the liberty of Englishmen in general, rather than enslaved peoples. For example, the two-year anniversary of Charles James Fox’s election to Westminster in 1780 was celebrated at the Shakespeare’s Head tavern in Covent Garden, where, of the 32 toasts given, one commemorated ‘The Tenth of October, 1780, the Day of the Emancipation of Westminster from Slavery’, meaning the breaking the monopoly of Government influence in the borough with the election of an Opposition candidate.[2] To take a later example, a print from Wootton Bassett in Wiltshire depicting an election procession in 1808 shows banners proclaiming ‘No Slavery’ alongside others asserting ‘The independence of Wootton Bassett’. Even though this was just a year after the abolition of the slave trade, both banners were actually boasting of breaking the long-held controlling interest in the borough of the local land-owning families.

Transatlantic Enslavement

But what we now call slavery – the trade in enslaved men, women, and children – was deeply embedded in British society and the nation’s economy throughout the long eighteenth century. Many MPs and their supporters owed their fortunes to the trade in enslaved people. Among the ECPPEC case study constituencies, Bristol and Liverpool had particularly strong links to the transatlantic slave trade. Sir Abraham Elton was a not untypical Bristol MP, for example, standing in 1722. He was described as ‘a pioneer of its brass foundries and iron foundries, and … owner of its principal weaving industry, as well as of its glass and pottery works, besides largely contributing to the shipping of the port’. But his business ventures were also linked with the trade in enslaved peoples, as the Annals Of The Elton Family recounts: ‘His profits … from making up shipments of those goods most attractive on the Gold Coast [of Africa] in return for slaves … were enormous’.

Given the slave trade’s centrality to British society and economy, it is perhaps surprising that slavery was often notably absent as a key campaign issue. Only later in the century can we notice the issue of transatlantic slavery becoming an important part of some candidates’ electioneering, with the campaign for abolition of the slave trade (if not yet always slavery itself) gaining strength from the 1760s. Initially, however, it is easier to find candidates arguing against abolition than for it. This resistance often stemmed from the financial investments of traders and merchants in many cities across the country, and particularly in ports. In 1796, Robert Sewell stood as candidate for Grampound. He had served as Attorney-General for Jamaica until 1795 and was later agent for the colony. Upon his election to the House of Commons, he went on to speak out against the abolition of the trade in enslaved peoples, and spoke in favour of plantation owners, members of colonial assemblies, and British merchants with interests in the West Indies.

Abolition

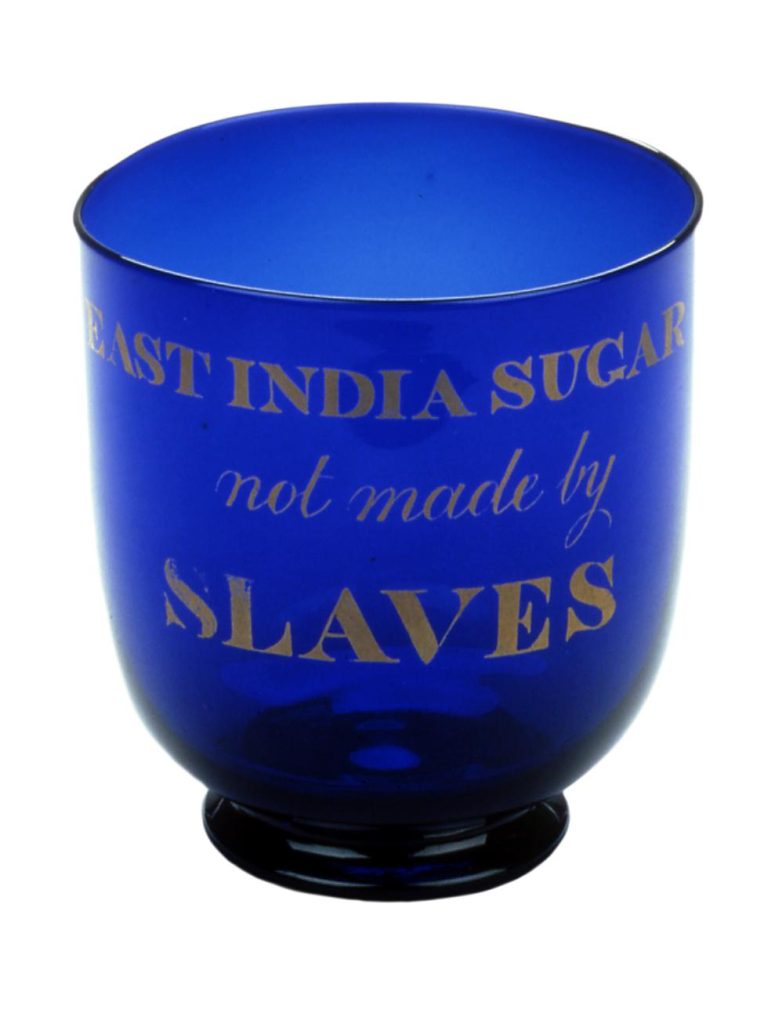

By the 1780s, the abolition movement gained momentum. Campaigners led meetings and boycotts to generate popular disapproval of slavery in Britain’s colonies, and boycotts of sugar produced on plantation estates by enslaved men and women were initiated in urban centres. Household objects were produced to highlight familial activism, such as the sugar bowls seen below, to make a political statement to visiting guests. In 1788, over 100 petitions demanding the abolition of the slave trade were submitted to Parliament in just three months. Naturally, then, the abolition campaign came to feature in elections too. The most celebrated abolitionist MP was William Wilberforce, member for Kingston-upon-Hull, before becoming Knight of the Shire for Yorkshire from 1784 to 1812. Alongside Wilberforce, there were at least two other active abolitionist campaigners in the House of Commons: Thomas Fowell Buxton, MP for Weymouth and Melcombe Regis from 1818 to 1837, and Stephen Lushington, MP for Great Yarmouth, Ilchester, and Tregony from 1806 to 1830. Despite the presence of abolitionists in the Commons, the paths to the Act to Abolish the Transatlantic Slave Trade in 1807, and later the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act, were by no means smooth. Abolition had both supporters and detractors, with the issue becoming an important topic in electoral campaigns particularly during flash points in abolitionist legislation.

The 1807 general election was particularly affected by the debate, given that the Slave Trade Act 1807 had been given Royal assent on 25 March 1807, very shortly before Parliament was dissolved. Candidates in favour of abolition sought to gain favour with the voterate by making their stances clear, for instance in the elections for Sussex, Rochester, Middlesex, Norfolk, Northumberland and Yorkshire.[3] In the Middlesex election, George Byng addressed the crowd from the hustings in Brentford, bringing up the recently-passed bill. A person from the crowd shouted, demanding to know whether Byng had supported the bill, to which Mr Byng responded, ‘I supported it 17 times out of 18, that it was discussed and agitated…’, resulting in cheers and exclamations of ‘Bravo!’ from the crowd.[4]

Abolition became a significant platform issue during the 1807 Yorkshire election in particular. Wilberforce’s record of campaigning for the abolition of the slave trade made him a favourite of Yorkshire’s Methodist community. Charles Fitzwilliam, Viscount Milton, another candidate, similarly espoused the cause of abolition during his campaign. The third candidate, Henry Lascelles, did not support abolition due to his family’s substantial interests in the West Indies. The Lascelles family owned six plantations with 1277 enslaved men and women in Jamaica and Barbados. Yet instead of positioning himself as overtly pro- or anti- abolition, a handbill from Lascelles’ election committee in Leeds asserted,

The Hon. H Lascelles’s character having been traduced as the abettor of the Slave Trade, with the view of injuring his interest in the present Election, the committee acting for Mr Lascelles, have his authority to assure the Freeholders of Yorkshire, that in case any attempt should be made in Parliament, to repeal the act, for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, such attempt will meet with his most decided opposition.[5]

Despite this lukewarm declaration that he would not support the repeal of abolitionist legislation, he did not advocate for the abolition of slavery more generally. As a result, anonymous handbills from ‘abolitionists’ were distributed, encouraging voters to cast their votes for ‘the Veteran and the Young Abolitionist [Wilberforce and Milton]’.[6] Indeed, Lord Milton’s election committee also planted mock advertisements for:

SUGAR-CANE

TO BE SOLD BY AUCTION,

By Messrs. Slavery and Juggle,

A large Quantity of Damaged SUGAR-CANE, of a blue colour [referring to Lascelles’ campaign colour], tinctured with a few red spots resembling drops of African blood, recently imported from Barbadoes [sic], and brought to the hammer to pay the expenses of a monstrous Coalition, formed betwixt saint [Wilberforce] and sinner [Lascelles]…[7]

Lord Milton campaigned for Yorkshire’s voters to cast their votes as plumps for his campaign (that is, casting only one of their votes and discarding the other in order to give that single candidate an advantage over the others). One way to encourage plumping was to plant the idea that Wilberforce and Lascelles were running in harness. The allegation was repeatedly denied by Wilberforce both during and after the election.

Even after the election, abolitionist slogans and imagery were used to celebrate the winning candidates. Following the final poll which saw Wilberforce and Milton elected, both candidates issued medals to commemorate their victories. Wilberforce’s pewter medal is edged with oak leaves and acorns, symbols of strength and wisdom, and emblazoned with the motto ‘Africa Rejoice!!’ The medal celebrates Wilberforce’s past accomplishments, including the abolition of the trade in enslaved peoples, flatteringly linking it to the independence of Yorkshire’s population.

For decades after the abolition of the slave trade, the campaign for the abolition of slavery itself continued. Even some candidates with familial connections to plantations in the West Indies campaigned for abolition. Edward Protheroe Jr came from a family of West Indian traders. To gain the support of Bristol’s Whigs during Bristol’s 1830 election, however, he declared that he supported the abolition of slavery, a position which ‘lost the support of many friends’ who called him a hypocrite. Protheroe well understood the popularity of the West India Planters’ interest in Bristol, but was optimistic: ‘the struggle will be considered as a trial of strength between the West India interest and the abolitionists … Already I am threatened not only with the united wealth and forces of the former in Bristol, but with the active co-operation in their behalf of the same interest in London’.[8] He positioned himself carefully as a friend of liberty, folding abolition of slavery into larger, more domestic discourses about freedom and his feeling for ordinary people. Upon his entry into Bristol, he let it be known that he did not want his supporters to pull his carriage through the city streets, saying, ‘that the man who came to advocate the emancipation of the negro could never allow white men, and especially his friends and fellow-citizens, to be yoked, in order to perform that labour which alone belonged to beasts’.[9] Placards filled Bristol’s streets and concerned campaigners took to the newspapers. One ‘Brother Freeman’ wrote, ‘vote for Protheroe and you promote your own freedom as well as that of the poor negro’.[10] Supporters of his opponent, James Evan Baillie, dubbed Protheroe ‘Negro Ned’, playing up the fear that the abolition of the trade in enslaved peoples would trigger the ‘loss of our colonies and consequently all that part of our transatlantic trade’. Ultimately, Protheroe’s campaign in Bristol was unsuccessful, with the return of Richard Hart Davis and Baillie, the latter of whom was supported by the local West India Planters’ interest.

Black Voters

In the eighteenth-century, there was no legislation blocking black men from casting their votes, provided that they met the other voting qualifications. For example, Ignatius Sancho was a tea dealer and grocer living in Charles Street in the parish of St Margaret and St John Westminster. Sancho was not only the first person of African descent to vote in Britain, but also an abolitionist and composer of country dances and minuets. His voting records can be found in the ECPPEC Data Explorer and in the transcribed poll books from 1774 and 1780. In 1774, Ignatius Sancho voted for Hugh Percy and Thomas Pelham Clinton, two Government candidates and sons of significant Westminster landowners, the duke of Northumberland and duke of Newcastle respectively. In 1780, Sancho split his vote between Government and Opposition candidates, voting for Sir George Brydges Rodney and Charles James Fox. In the early nineteenth century, George John Scipio Africanus, owner of an employment agency for fellow local black Britons, waiter, and labourer, was also found to have voted in Nottingham in 1818, 1820, and 1826, voting for the largely unsuccessful Tory candidates.[11] While these men provide only two examples, there are likely to be other examples of black voters to be discovered, adding greater nuance to the diverse political participation and electoral engagement of the long eighteenth century.

In sum, slavery and abolition became increasingly important electoral issues in the latter half of the eighteenth and into the nineteenth century, and were an important sphere of popular political participation through petitions, print campaigns, consumption practices, boycotts and so on. That said, for an issue that we might now assume to have had such political significance and moral weight, it can also be surprising how little the trade in enslaved people featured in election campaigns. African slavery is both present and not present in the parliamentary campaigns of this period then, and we require more work to discover just how deeply it permeated electoral culture.

[1] Srividhya Swaminathan and Adam Beach, ‘Introduction’, in Invoking Slavery in the Eighteenth-Century British Imagination, ed. by Srividhya Swaminathan and Adam Beach (Routledge, 2016), 9-10.

[2] Derby Mercury (10 October 1782), p. 2 col. b.

[3] Sun [London] (22 May 1807), p. 2 col. a; Kentish Weekly Post or Canterbury Journal (8 May 1807), p. 4 col. c; Morning Advertiser [London] (19 May 1807), p. 3 col. b; Norfolk Chronicle (16 May 1807), p. 2 col. e; Morning Chronicle [London] (26 May 1807), p. 3 col. d.

[4] Morning Advertiser [London] (19 May 1807), p. 3 col. b.

[5] Yorkshire Election. A Collection of the Speeches, Addresses and Squibs, produced by all the parties during the late contested election for the County of York (Leeds: Baines, 1807), 22-3.

[6] Yorkshire Election, 33.

[7] Yorkshire Election, 42.

[8] Brougham Mss, Letter from Protheroe to Brougham, 22 July 1830.

[9] Bristol Mirror (24 July 1830).

[10] Peter Marshall, Bristol and the Abolition of Slavery: the politics of emancipation (Bristol Historical Association, 1975), 16.

[11] Helen Wilson, ‘The Presence of Black Voters in the 18th and 19th Centuries’, History of Parliament Blog (2022) <https://thehistoryofparliament.wordpress.com/2022/10/18/the-presence-of-black-voters-in-the-18th-and-19th-centuries/>