A strongly Tory agricultural county, dotted with manufactures at Bicester (leather), Henley (silk) and Witney (blankets), Oxfordshire emerged from the Glorious Revolution with a Tory hegemony led by the Earls of Abingdon, supported by the majority of the county gentlemen.

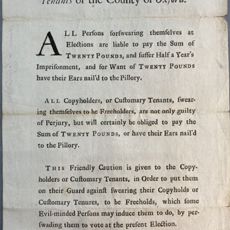

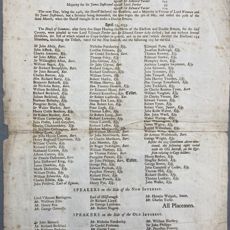

The Whig opposition was small, but vocal. The University, which had its own representation, gained a strong reputation for Jacobitism in the first half of the eighteenth century. The labelling of all Tories as Jacobites and the use of the press to support this charge dates as far back as the hotly contested election of 1690 and the circulation of a printed list of all those members of the Convention who had opposed offering the crown to William and Mary.

Despite a contested election in 1698 and the arrival in 1705 of a potential leader for the county Whigs in the figure of the Duke of Marlborough, who had been granted the royal manor of Woodstock by Queen Anne, the county remained staunchly Tory. An arrangement between the local Tory grandees and Marlborough saw Marlborough’s son-in-law Viscount Rialton (later Earl of Godolphin) share the county representation briefly between 1708 and 1710, but subsequent Whig challenges during Queen Anne’s reign failed. Between 1715 and 1754 Whig commitment to challenge Tory control of the county faltered and there were no contested elections: the county consistently returned two Tories unopposed.

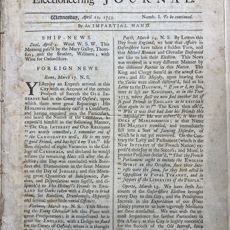

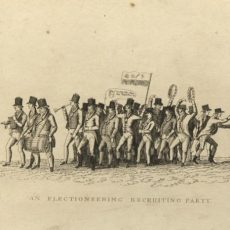

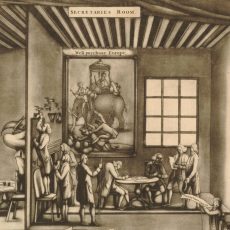

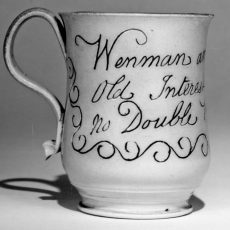

The peace of the county was broken in 1752 with the beginning of what would be a fierce and immensely expensive two-year campaign by the Whig New Interest to overthrow the Tory Old Interest in advance of the 1754 general election. A revived Whig interest, led by influential local peers with close connections to the Administration and the court — the Duke of Marlborough and Lords Macclesfield and Harcourt — was assisted financially by the Pelham Administration. Oxford University not only provided a ready source of satirists and hack writers, but also saw colleges and halls take political sides, with the election and subsequent scrutiny serving to settle a score between two old academic enemies — the Whig, Richard Blacow, Canon of Windsor and ex-fellow of Brasenose College, and the old Jacobite, William King, the Principal of St Mary’s Hall. A hotly contested and irregular election, that involved Exeter College allowing New Interest voters to outflank their rivals through the college grounds, was followed by an inconclusive scrutiny and a double return (i.e. declaring both pairs of candidates to have been elected, and leaving the House of Commons to decide who had been lawfully elected). Both sides petitioned and the Whig New Interest candidates were finally seated a full year after the initial election.

The cost, effort and vitriol of the 1754 election was such that neither party was keen to see it repeated. As a result the leaders of the two parties came to a compromise and agreed to split the seats in 1760. While this compromise would hold true right up until 1826, the dominance of the Marlborough interest was undermined by internal family arguments and disagreements from the 1796 election onwards and had been effectively eclipsed by 1815.