Nigel Aston on the peculiar representation of Oxford and Cambridge universities [15-minute read]

University constituencies and their distinctive characteristics

The Universities of Oxford and Cambridge had each been granted two parliamentary seats by James I in 1604 and stood apart from the customary county/borough divide. They existed, in the words of the great jursit Sir William Blackstone, ‘to serve for those students who, though useful members of the community, were neither concerned in the landed nor the trading interest; and to protect in the legislature the rights of the republic of letters’.[1] They survived until the coming of a democratic franchise and were only abolished in 1950. The original Letters Patent talked of the franchise as bestowed upon the ‘Chancellor, Masters, and Scholars’ of each University, but the sense was a century later that the term ‘Scholars’ had become redundant.[2] They had some characteristics that were not typical of the wider electoral scene. First, they had a secret or semi-secret method of voting; secondly, there was no property qualification for either voting or sitting in Parliament. All that a voter had to possess to exercise his franchise was membership of Convocation (Oxford) or the Senate (Cambridge). MPs (or burgesses as they were officially called) were also exempted from owning landed or personal property as specified in the Property Qualifications Act, 1711 (9 Anne, c. 5).[3] Finally, universities in theory, legal status, and usually practice, made great play of their removal from external influences (including the Crown’s) at election time. Ministerial influence was invariably at play but there was always the possibility that university independence would exert itself unpredictably and voters could not be taken for granted.

Voting qualifications

In both seats, all voters were legally required to be Anglicans, a reflection of their status as members of confessionally exclusive academic establishments. In Cambridge members of the Senate (the governing body of the University), that is men holding a doctorate or Master of Arts degree, were entitled to vote. An individual was required either to pay £4 or £5 yearly to be kept on the books of his college, or be registered as commorantes in villa, that is resident in the borough but unattached to a college. In Oxford, members of Convocation (its governing body) could all vote. The majority of these were the resident senior members of the University, usually college fellows living in Oxford. But there were also many potential non-resident voters (extranei as they were called) whose names figured on their college’s books for six months prior to an election, and they could be keen to cast their votes in a contested poll.[4] In both places most general elections brought with them disputes about franchise entitlement, not helped in Oxford by the absence of any official list of members of Convocation.[5] In Oxford, it was the college authorities who had control of the buttery books (the college ledgers detailing a student’s expenses) and senior resident dons in most colleges and halls were likely to favour a narrow interpretation of eligibility. Thus when the Jacobite firebrand Dr William King stood against the sitting MPs, William Bromley and George Clarke, in the General Election of 1722, it appears that some college heads struck out the names of non-resident graduates they considered were likely to vote for William King. In its aftermath, they even had a paper prepared by counsel on their behalf that somewhat tendentiously articulated this interpretation of the franchise.[6] A further clarification of the basis of the University franchise looked desirable to most parties, though the obstacle was, as always, the Laudian statutes of 1636 that governed the running of Oxford University. Eventually, in 1759 a form of statute was drafted by the hebdomadal board (the governing council of the university) for regulating membership of convocation. This explanatory statute was passed at the second attempt in July 1760.[7]

The number of electors

In Oxford, the electorate was somewhere between 350 and 500 persons in total in the early eighteenth century, each with two votes. The number showed a steady increase in the course of this period (in part because of the clarificatory 1760 statute); whereas 361 voted in 1701, 493 did so in 1768, a figure rising to 1,116 by 1805.[8] The Cambridge University electorate was approximately 500 in the later eighteenth century having increased from 193 in 1692. By c.1800 the figure was approximately 800.[9] By comparison, the borough c.1780 numbered about 150 voters, and the county of Cambridgeshire about 3,000.[10] Voting lists in the eighteenth century have been laregly preserved. The printed polls give the names of the voters arranged by colleges, the persons for whom they voted, and the total scores. Their circulation in print was considered impermissible (though it did happen), a breach of faith contravening a vote that was technically private and given exclusively to the university tellers on the day of the poll.[11]

The performance of voting

Voting in both constituencies took place in person over one day or, occasionally, half a day. At Cambridge, electors voted on written slips that were placed inside a ballot and given to the Vice-Chancellor, who acted as the returning officer; at Oxford there was an official list that could be disputed. At an Oxford poll, the Vice-Chancellor claimed the right to find fault with the qualification of individual electors via the scrutators who, though sworn to secrecy, reported to him as returning officer. University elections at Oxford cost successful candidates – in theory – nothing, except for small fees and gratuities to the bedells who brought them news of the result, and some other minor officials.[12] Candidates were not present when the results were declared; burgesses could return afterwards to pay formal visits to the heads of colleges. In the event of a close fought contest (as in 1722 in Oxford), a defeated candidate could always ask for a scrutiny to be held.

The selection of candidates

In the selection of candidates, the influence of the larger colleges with their distinctive corporate traditions could be paramount. In Oxford selection also entailed the endorsement of the governing Hebdomadal Board and one or all of the three colleges most closely connected through their alumni and their governing bodies to national politics – Christ Church, Magdalen College, and All Souls College. Their wishes were generally upheld. The dean and chapter of Christ Church thus in 1801 insisted on endorsing the legal luminary and talented don, Sir William Scott, as one of the University’s two MPs, while leaving the other seat open to the wishes of the rest of the University.[13] In Cambridge, the three largest colleges, Trinity, King’s, and St John’s, accounted for half the electorate, and had a proportionate influence in choosing candidates.

The frequency and nature of contests

Elections seldom involved a poll; pre-electoral campaigning usually indicated the stregth of an individual candidature and withdrawals were common. And it was conventional for an Oxford University MP who sought re-election to be returned unopposed. Whereas, in the late Stuart era, contests were a regular feature of Cambridge University politics when party configurations were both complicated and evolving, at Oxford managers were anxious to avoid them. There were no contested elections at Cambridge between 1734 and 1771, an era that approximately coincided with the chancellorship of Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st duke of Newcastle (1748-68) when the University was, in the phrase of the parliamentary historian, John Brooke, ‘little better than one of Newcastle’s boroughs’.[14] National political issues, in the Hanoverian era, such as attitudes towards British involvement in the American War of Independence, were inevitably intrusive and made for internal volatility. Thus in the 1779 by-election at Cambridge, many of the university’s younger anti-government electors backed the Hon. John Townshend, a Rockingham Whig, but the successful candidate, James Mansfield, KC (who had the Chancellor’s endorsement) took a pro-government line in the Commons, and he was appointed Solicitor-General in 1780.[15] The 1780 general election witnessed five candidates standing for the two Cambridge seats, with the Chancellor (the 3rd duke of Grafton) backing the opposition supporters and the Vice-Chancellor the ministerial ones.[16] At Cambridge, candidates could come and go and canvas as they pleased whereas in Oxford, there was a rubric that prohibited them from canvassing in person or coming within ten miles of the University at election time. Speeches were also prohibited in both places, though papers might be sent around common rooms relating to the election, as in January 1750 at Oxford, questioning the eligibility of one of the candidates, Sir Edward Turner. There might also be toxic and generally anonymous exchanges in pamphlets or the newspapers at election times, as in the Oxford election of 1722. None of these limitations could forestall the supporters of competing candidates from exchanging insults and much unofficial lobbying within and between the colleges and halls.[17] There could be weeks of horse trading, intrigue, intercollegiate alliances, misinformation, threats, promises, and ‘treating’.[18] In 1705 by the high-flying Tory candidate, Sir Humphrey Mackworth, even sent crates of wine to college common rooms in the hope of eliciting votes.[19] A century later, Sir William Scott, with a greater sense of decorum that did his campaign no harm, neither addressed nor canvassed, but left it to influential friends to secure his re-election.[20]

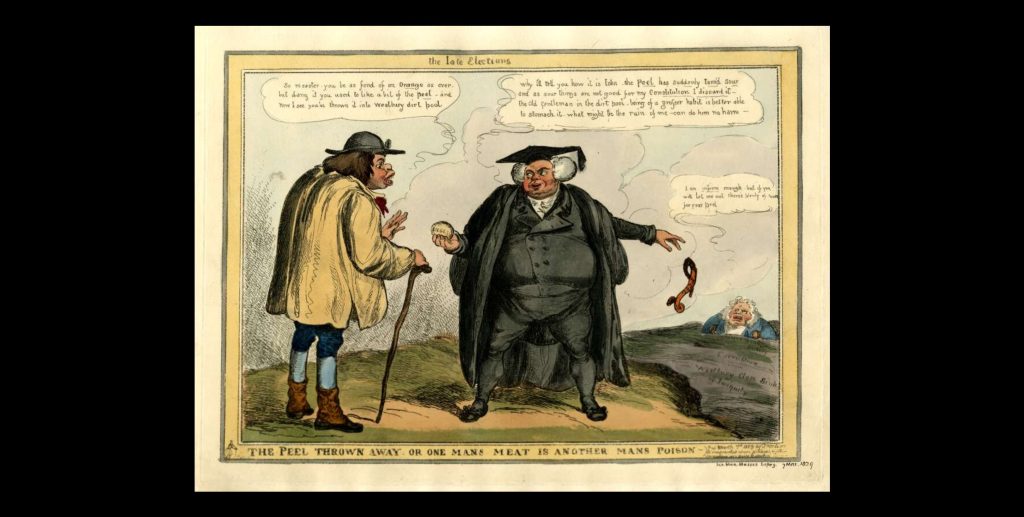

This was in the spirit of the Oxford convention that its MPs should be put to no personal expense in connection with their election.[21] By this date the precedent that no sitting member should be opposed was well-established, but it was hard to maintain in practice because of internal divisions on major political issues (such as Catholic Emancipation) and the closer relationship between Oxford University and ministers. ‘No Popery’ was a key issue in the 1807 General Election at Cambridge when Lord Henry Petty’s candidature for re-election suffered from his endorsement of Emancipation. As the celebrated Whig headmaster and classicist, Samuel Parr reported: ‘on the walls of our senate house, of Clare Hall chapel, and of Trinity Hall, I saw the odious words [i.e. No Popery], in large characters’.[22] Petty was squeezed into fourth place just over a year since replacing William Pitt the Younger as University MP. This was a foretaste of the Tory Robert Peel’s (Home Secretary) defeat at Oxford in 1829 when he, along with the duke of Wellington (Premier), decided emancipation must be carried. He resigned his seat for the University, and there followed the most acrimonious by-election when Sir Robert Inglis triumphed by 755 to 609 votes. Inglis retained his seat until 1854.[23]

Inward-looking constituencies

With the franchise confined strictly to Oxford and Cambridge graduates, wider participation in university elections appears to have been nominal. With neither hustings to witness nor speeches to hear, and canvassing conducted primarily and privately within colleges, the interest of the citizenry was minimally engaged. Besides, both Oxford and Cambridge were also the polling centres for borough (and county) elections, and it was in those contests that men and women outside the academic franchise tended to interest themselves.

The background of University MPs

While both universities prided themselves on their independency but the goodwill of ministers was essential if crown patronage was to flow in their direction. The Whigs finally prevailed in Cambridge during the early Hanoverian era while Oxford flourished under George III after Jacobitism had ceased to be a meaningful political option for disgruntled Tories and the University’s historic loyalty to the crown could be expressed without public or private qualification. In the second half of this period, University burgesses were more likely to be close to the government. Indeed, between 1784 and his death in 1806, Cambridge University returned the Prime Minister (and its own High Steward), William Pitt the Younger, as one of its MPs.[24] His dominance was such that no opposition candidate was put up to stand against him at the 1796 General Election. He and the Earl of Euston (Grafton’s son) monopolised the university’s representation for two decades, as majority opinion in the university rallied to the defence of the crown and the Church in the wake of the French Revolution. It was by no means unusual for an academic to serve as a University MP. Hence the presence in the Commons between 1737 and 1745 of Dr Edward Butler, the serving President of Magdalen College, Oxford, and a former Vice-Chancellor (1728-32) and, most famously, of Isaac Newton, Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, in 1689 and 1701. But, more usually, the representatives of the universities tended to be independent-minded country squires of Tory inclinations. Some made slight impact in Parliament, as Francis Page, burgess for Oxford University from 1768; others, such as Sir Roger Newdigate, MP from 1751 to 1780 (a major benefactor), and Sir William Dolben, MP from 1780 to 1806 (a leading anti-slavery protagonist), were nationally respected. Whigs made no progress in the polls at Oxford in this era. The lawyers and orientalist, William Jones (fellow of University College) told John Wilkes after his defeat in 1780: ‘A Whig candidate for Oxford will never have any chance except at a time (if that time should ever come) when the Tory interest shall be almost equally divided’.[25] In Cambridge, the Finch family (Earls of Winchelsea and Nottingham) had an hereditary influence down the generations (despite or, perhaps, because of their switch from Tory to Whig), one that reached its culmination in the seat held by the Hon. Edward Finch continuously from 1727 until 1768 (his seat was contested only twice, in 1727 and 1734). As with the continuously parliamentary presence later of Pitt and Euston, it was a sign that the university had arrived ‘at a large measure of political consensus.’[26]

[1] William Blackstone, Commentaries on the laws of England (originally published Oxford, 1765–9), W. Prest. gen. ed., Book 1: Of the rights of persons, David Lemmings, ed. (Oxford, 2016), 115.

[2] M. Rex, University representation in England, 1604-1690 (London, 1954), 60-1.

[3] Edward Porritt assisted by Annie G. Porritt, The unreformed House of Commons; parliamentary representation before 1832 (2 vols., London, 1903), i, 103.

[4] The franchise is authoritatively discussed in L.S. Sutherland, ‘The Laudian Statutes in the Eighteenth Century’, in The History of the University of Oxford. Vol v. The Eighteenth Century, [HUO] ed. L.S. Sutherland and L.G. Mitchell (Oxford, 1986), 191-203, esp. 195-6.

[5] Peter Searby, A History of the University of Cambridge: Vol. 3: 1750-1870 (Cambridge, 1997), 52; Rex, University Representation, 58-60.

[6] University of Oxford Archives: MS. SP/C/6, ‘Concerning the Qualifications of an Elector in the Elections of Burgesses for the University of Oxford’, dated 1723.

[7] John Griffiths, Statutes of the University of Oxford codified in the year 1636 (Oxford, 1888), xvi-xix, 310-13. See also Wilfrid Prest, William Blackstone. Law and Letters in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford, 2008), 172-5; Sutherland, ‘Laudian Statutes’, 198-203..

[8] http://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1754-1790/constituencies/oxford-university

[9] http://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1690-1715/constituencies/cambridge-university

[10] See Daniel Cook, ‘The Representative history of the County, Town and University of Cambridge, 1689-1832’ (University of London, Ph.D, 1935).

[11] Porritt and Porritt, The unreformed House of Commons, i, 103.

[12] BL Add. MSS. 40266, ff. 134-5.

[13] W.R. Ward, Victorian Oxford (London, 1965), 22-3.

[14] http://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1754-1790/constituencies/cambridge-university; John Gascoigne, Cambridge in the age of the Enlightenment: science, religion and politics from the Restoration to the French Revolution (Cambridge, 1989, 89.

[15] HPC, 1754-1790, s.v. Mansfield, James

[16] Gascoigne, Cambridge in the age of the Enlightenment, 211-12.

[17] Thomas H.B. Oldfield, An entire and complete history, political and personal of the boroughs of Great Britain History of Boroughs (2 vols., 1792), ii, 387.

[18] Rex, University Representation, 72.

[19] M. Ransome, ‘The parliamentary career of Sir Humphrey Mackworth, 1701-1713’, University of Birmingham Historical Journal, i, (1947-8), 232-54.

[20] TNA, PRO 30/9/16, Sir W. Scott to Charles Abbot, 22 Sept. 1812.

[21] [J.R. Green], Oxford During the Last Century Oxford, 1859, 18.

[22] William Field, Memoirs of the life, writings, and opinions of the Rev. Samuel Parr, LL.D. (2 vols., London, 1828), ii. 21.

[23] Norman Gash, ‘Peel and the Oxford University election of 1829’, Oxoniensia 4 (1939), 162-73.

[24] Searby, A History of the University of Cambridge, 412-14; David Cowan, ‘Pittite triumph and Whig failure in the Cambridge University constituency, 1780-96’, in M.O. Grenby and Elaine Chalus, eds, ‘Elections in 18-th century England: polling, politics, and participation’, Parliamentary History (2024), 91-111.

[25] 7 Sept. 1780, BL, Add. MS 30877, f. 90.

[26] Gascoigne, Cambridge in the age of the Enlightenment, 214.