Pamela Clemit uncovers Godwin’s report on two tightly fought metropolitan polls [15-minute read]

The 1818 general election was the first to be held after the Napoleonic Wars. Wellington’s decisive victory at Waterloo in 1815 ended twenty-three years of almost uninterrupted war, and by 1817 Britain was experiencing a severe economic downturn. Mass unemployment, rising food prices, and falling wages led to riots and protests orchestrated by militant radicals calling for parliamentary reform. This prompted Lord Liverpool’s Tory government to suspend habeas corpus and introduce a series of repressive public order measures.

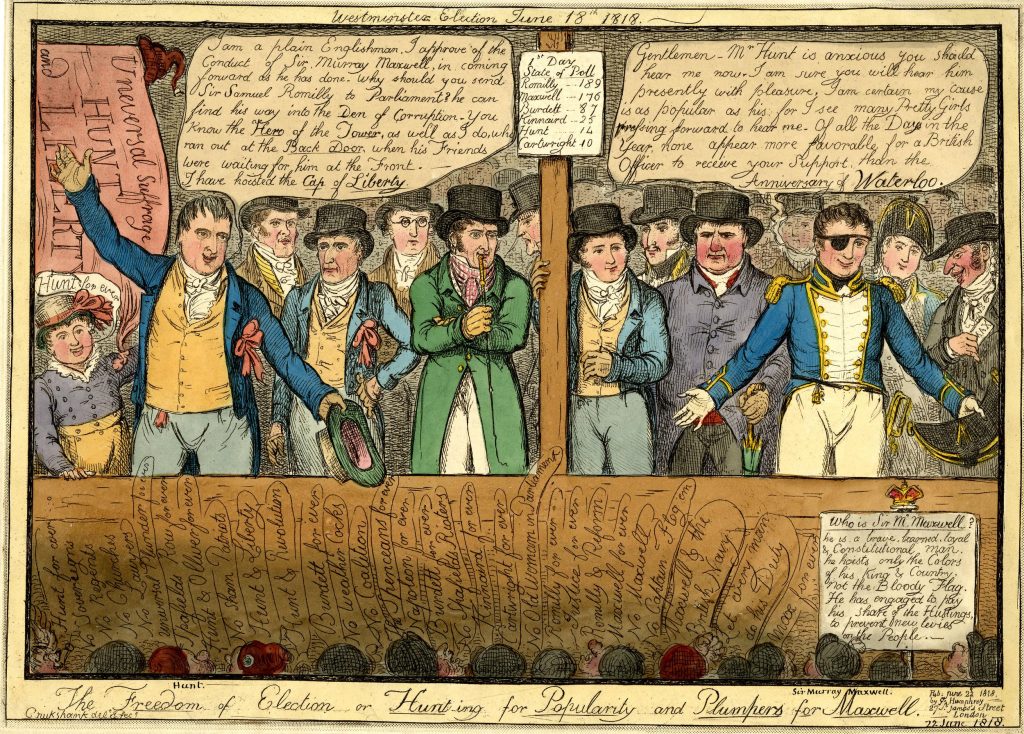

The general election of 1818 gave a platform to anti-establishment candidates associated with the radicalism emanating from manufacturing districts, as well as to progressive Whigs. The contest lasted from 17 June to 18 July and was intensely fought. Over 30% of all constituencies went to the poll at a time when uncontested seats were a well-established norm. The growth of the post-war popular movement for parliamentary reform greatly influenced metropolitan politics. The constituencies of London, Westminster, and Southwark were the most important radical strongholds, encompassing a diversity of anti-ministerial opinions.

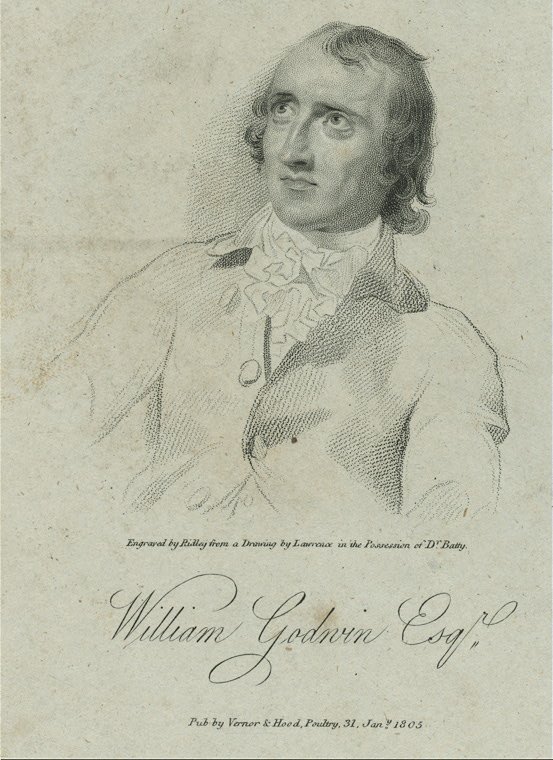

The letters of William Godwin, who kept a shop in the City of London, provide an individual perspective on the metropolitan contest as it unfolded. Godwin was no ordinary tradesman. The radical polymath had risen to fame in the 1790s as the author of An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793), a founding text of philosophical anarchism, and the novel Things As They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams (1794), in which he attacked aristocratic privilege. Towards the end of the decade, the conservative press launched a popular campaign to discredit his views. Godwin looked for other ways to continue his life’s work. In 1805 he set up a children’s bookshop and publishing imprint. Two years later he moved to larger premises at 41 Skinner Street, Holborn. In 1808 he became an admitted freeman of one of the 89 livery companies which were a constituent part of the governance of the City of London.[1] This gave him the right to vote in general elections.

Godwin provided a commentary on the electoral contest in the metropolis in two letters to his daughter Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, who had settled in Italy with her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley in March 1818. In another letter, to his protégé Joseph Vallence Bevan, a young American visiting Britain for the first time, he described the voting process and engaged in some philosophical reflections on the Georgian electoral system as a whole.

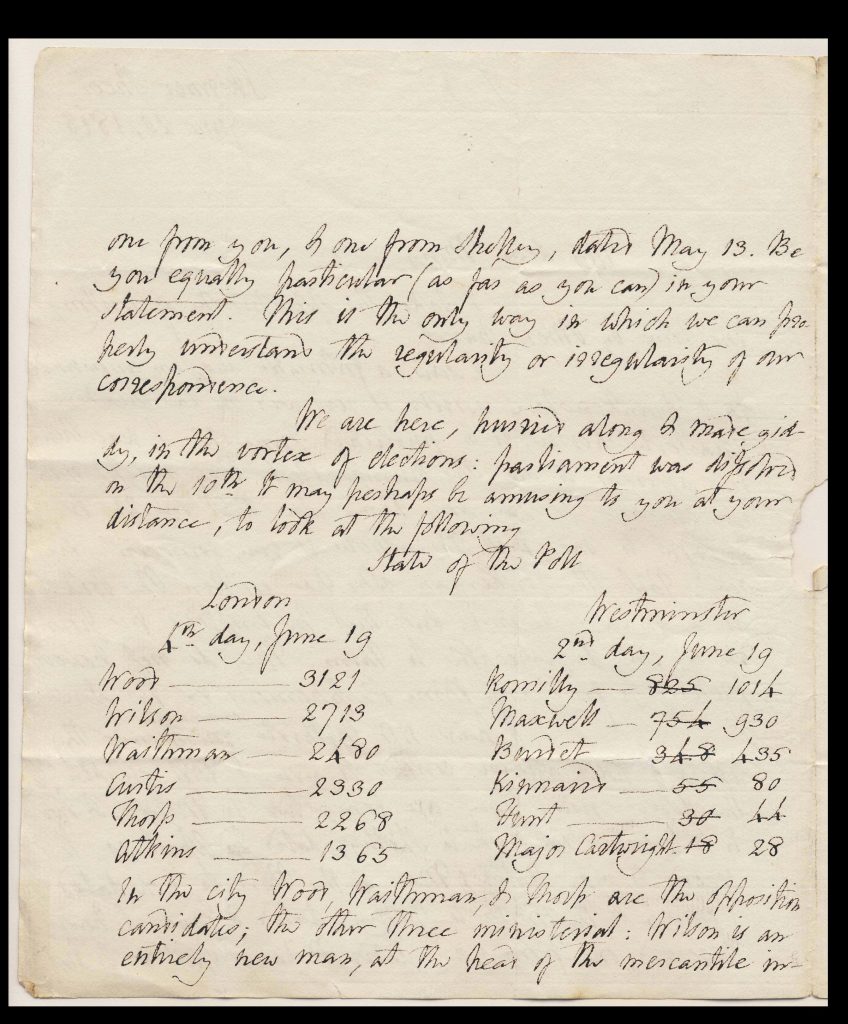

In his first letter to Mary Shelley, dated 20 June 1818, Godwin gave a snapshot of the state of the poll in London (which returned four members to Parliament) and Westminster (which, like almost every other constituency, returned two):

We are here, hurried along & made giddy, in the vortex of elections: parliament was dissolved on the 10th. It may perhaps be amusing to you at your distance, to look at the following

State of the Poll

London Westminster

4th Day, June 19 2nd day, June 19

Wood ——– 3121 Romily ——

8251014Wilson ——- 2713 Maxwell —-

754930Waithman — 2480 Burdet ——-

348435Curtis ——- 2330 Kinnaird —-

5580Thorp ——- 2268 Hunt ——–

3044Atkins —— 1365 Major Cartwright —

1828

In the city Wood, Waithman, & Thorp are the opposition candidates; the other three ministerial: Wilson is an entirely new man, at the head of the mercantile interest. For Westminster, Sir Murray Maxwell, captain in the navy, is the only ministerial candidate: Lord Cochrane resigned; & the Jacobins put up Kinnaird with Burdet, as their two favourites; but they seem to have played their cards very ill. You will of course recognise in Hunt the leader of the Spa Fields riots; his principal oratorical supporter is Gale Jones. The elections will continue for eight or ten days in each place.[2]

Godwin drew his figures from the table published in the Morning Chronicle on the date of his letter.[3] The table shows that the contests in each constituency were staggered rather than beginning on the same day. In the column for London, he gave the total number of votes for each candidate over the first four days. In the column for Westminster, he first gave the numbers from the second day of polling, and then crossed them out in favour of the total number of votes for each candidate over the first and second days. These changing figures capture the fluctuating support for particular candidates in each constituency.

London was a tightly fought contest. There were three ‘opposition candidates’, as Godwin reported. All were tradesmen prominent in City politics, but with no previous parliamentary experience. By the fourth day of polling, Matthew Wood, an advocate of parliamentary reform who had just finished a two-year term of office as Lord Mayor of London, was in the lead by 408 votes; Robert Waithman, his fellow-radical, was in third position; and John Thomas Thorp, who stood as an independent friendly to parliamentary reform, was trailing near the bottom of the poll. The two incumbent Tory MPs, Sir William Curtis and John Atkins, were in fourth and sixth places respectively. In second place was ‘an entirely new man’, Thomas Wilson, a spokesman for the City’s shipping and mercantile interests, whom Godwin described as ‘ministerial’, but who subsequently declared himself to be of no party.

The Westminster contest began in disarray. Godwin called the metropolitan radicals ‘Jacobins’, invoking the struggle for reform in the 1790s in which some of them had participated. Opposing factions on the Westminster committee proposed different partners for the radical incumbent Sir Francis Burdett, who was the undisputed leader of the movement for parliamentary reform. The two running mates were the veteran political reformer John Cartwright, one of the earliest advocates of universal suffrage, and the politically inexperienced banker Douglas Kinnaird, who also pledged support for universal suffrage. The division among metropolitan radicals was exploited by the Whigs. They put forward Sir Samuel Romilly, the legal reformer, on the understanding that he would neither canvass nor appear at the hustings.

By the second day of polling, the radicals were plunged into crisis. Romilly had 1014 votes, the ministerial candidate Sir Murray Maxwell 930, and Burdett merely 435. The candidacy of Henry Hunt, a champion of militant popular radicalism, further divided the anti-ministerial vote (though it proved electorally insignificant). Something had to be done to safeguard Burdett’s seat. The withdrawal of Kinnaird and Cartwright from the contest was announced from the hustings at the close of polling on 20 June around 4 p.m.,[4] just hours too late for Godwin to include the news in his letter of that date.

In his next letter to Mary Shelley, dated 7 July 1818, Godwin reported the outcome for the whole of the metropolis:

The Westminster election closed on Saturday; & the result of the whole in this division is, that the metropolis, which sends eight members, four for London, two for Westminster, & two for Southwark, has not sent in its whole number one old supporter of the present administration. The members for Westminster are Romilly & Burdet; for Southwark Calvert, a veteran Foxite, & Sir Robert Wilson; & for London alderman Wood, alderman Thorp, & Waithman, all stanch oppositionists, & Mr Wilson, a merchant, a new man, who will in all probability vote for government, but who at least is not an old supporter. Sir William Curtis for London, their right-hand man, is thrown out.[5]

Polling in Westminster had lasted fifteen days. According to the Morning Chronicle, Burdett finished 101 behind Romilly, who polled 5339 votes (and 435 ahead of Maxwell, who was financially ruined by the campaign).[6] Romilly’s success was seen as a tactical victory for the Whigs over the radicals and a blow to Burdett’s prestige.

In Southwark, Charles Calvert, the Whig incumbent, came top of the poll with 1932 votes; the army officer Sir Robert Wilson, long associated with the Whigs but a novice parliamentary candidate, finished in second place with 1377 votes, ousting the second incumbent, the pro-ministerial Charles Barclay.[7] In London, where polling lasted seven days, Wood finished at the top of the poll with 5715 votes, Thorp won 4349 votes, and Waithman 4617. Wilson, the ‘new man’, pulled in 4846 votes. Curtis slipped to fifth position, losing the seat he had occupied since 1790, and Atkins, the other incumbent Tory, stayed at the bottom of the poll, with 1693 votes.[8] It was a triumph for the City radicals and a humiliating defeat for the ministerial interest.

The expulsion of the ministerial party from the metropolitan constituencies prompted Godwin to observe: ‘every body is of opinion, that if time had been given, & these examples had been sufficiently early, the general defeat of the ministry would have been memorable. As it is, it is computed that the ministerial majority will immediately be diminished by forty or fifty votes; & sanguine people say, Nobody can tell what that may end in.’[9] Such an estimate was wide of the mark. It took into account only the ministry’s losses and overlooked their gains in small, often corrupt, constituencies. This reduced the Whig Opposition’s overall gains to six MPs and gave Liverpool’s ministry a comfortable majority of around 90 MPs.

Godwin was not just interested in the outcome of the election. He was also engaged by the process of voting. Votes were declared publicly at the hustings—the secret ballot was not introduced until 1872. Those entitled to vote went forward in tallies, groups of ten to twenty men supporting the same candidate. If rival factions ran into each other, there was a risk of violence. Onlookers cheered or heckled. Godwin viewed the panoply of a general election with insouciance. He regarded voting as an expression of civic virtue. On 29 June 1818, he wrote to Joseph Bevan, then in Dublin, giving a philosophical perspective on the British electoral system:

I congratulate you upon your good fortune, in being in the British Islands at the time of a general election. This is an instructive, & in some respects an animating spectacle. … I am pleased with the open avowal our electors make of their sentiments. I am pleased with the sympathy excited in their breasts by their general congregating to the place of election, thus reviving (though alas! but once in seven years) the practical & healthful feeling, that they are freemen. I am pleased with the scene of an election protracted for four or five days, & thus nourishing the love of what is right, by some degree of uncertainty & suspense respecting the event. I am an enemy to mobs; but this sort of mob, or confluence of mankind, expressly directed by the law, & terminating in a specific act, seems to me to be deprived of the sting, the terror, & the hot-blooded, savage, & dangerous feeling, attendant on bodies of men, called together at their own pleasure, & chusing for themselves the sort of exertion to which their power shall be directed.[10]

Godwin adopts the stance of a bystander, but may have been a participant. Did he use his vote? There are no surviving poll books for the City of London after 1796 and before 1832, and no other proof positive has been found. The question remains open.

[1] Godwin was admitted as a member of the Worshipful Company of Needlemakers and to the Freedom of the City of London on 5 Nov. 1808 (Guildhall Library, London Metropolitan Archives, MS 2818.003, fol. 40r, 2817.005, fol. 109r).

[2] Bod. MS Abinger c. 45, fols. 9v-10r, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. All MS letters quoted in this piece will be published with full scholarly apparatus in The Letters of William Godwin, Volume IV: 1816-1828, ed. Pamela Clemit (Oxford, forthcoming 2025).

[3] Morning Chronicle, 20 June 1818.

[4] Morning Chronicle, 22 June 1818.

[5] Bod. MS Abinger c. 45, fol. 13r-v, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

[6] Morning Chronicle, 6 July 1818.

[7] Morning Chronicle, 22, 23 June 1818.

[8] Morning Chronicle, 24 June 1818.

[9] Bod. MS Abinger c. 45, fol. 13v, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

[10] Bod. MS Abinger c. 19, fol. 66v, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.