Candidates’ processions before and after elections were colourful and noisy events [15-minute read]

From the issuing of the writ of election to the chairing of the successful candidates, parliamentary elections were replete with ritual, often long established by precedent within each community. Notably, these rituals included both voters and non-voters alike. Processions in particular were events deliberately designed to encompass the entire community. Crowds could be massive. When Daniel Coke was chaired around the marketplace in Nottingham in 1803, for example, it was said that he was met with the cheering of twenty thousand constituents, constituting more than two-thirds of Nottingham’s entire population, and ten times as many people as had actually voted.[1]

Elections were frequently bookended by processions. The start of a campaign was often signalled by the ceremonial entry of a candidate into the constituency, a visual and immersive indicator of the beginning of intensive campaigning (though prospective and incumbent candidates could treat constituents for months and even years before an election was called). A visually impressive and participatory procession organised by his supporters was used to generate excitement and encourage, or perhaps gauge, support. Richard Hanbury Gurney, a Quaker and partner in Gurney’s Bank of Norwich, had been elected as MP for Norwich from 1818 to 1826 for the ‘Blue and White’ party, before stepping down over his poor health. However, on his return to Norwich politics in 1830, his carriage entering the town ‘was greeted by fifteen to twenty thousand people and by a procession a mile long, if the surviving descriptions can be believed’.[2] The spectacle was orchestrated to incorporate men, women, and children into the procession as active participants, not as passive bystanders to the electoral drama. Once the procession reached the town, it was common for the horses drawing the carriage to be removed, and the carriage to be drawn by the constituents through the town streets.[3] Processions might even start far outside the constituency itself. For example, Lady Spencer provided this account to her children of the return of Lord Spencer’s candidate, Thomas Howe, to Northampton in 1769 following a scrutiny of the result of the previous year’s election:

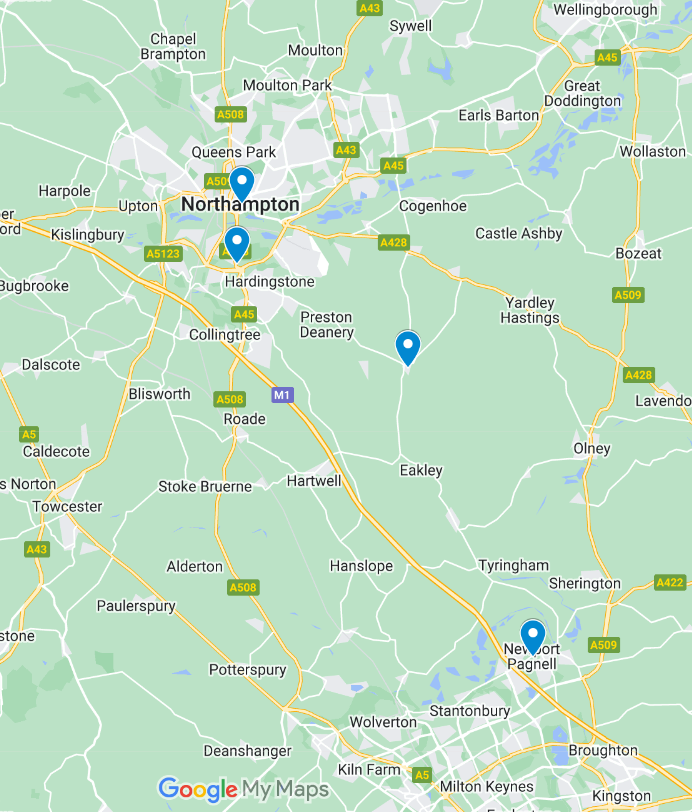

I could not help wishing you had been with me when we entered the town of Northampton as you would have liked all the show and bustle very much, we were met by vast numbers of men on horseback all with blue cockades in their hats the whole way upon the road from Newport Pagnell, particularly at Horton where there was a body of nearly 200 of them… a loud huzza and then join our train at Queens Cross there was a much larger number of them with several Gentlemen and principal people of the town, there your Papa and Mr Howe got out their post chaise and proceeded slowly to the town on horseback at the entrance of the town there was a vast crowd of people, with a flag on which was wrote in great gold letters Justice Triumphant… the Crowd was so great in the Streets that we were above three Quarters of an hour driving up the great Street.[4]

The route extended over fifteen miles, and might have taken over five hours on foot. At each stage of the procession, in Newport Pagnell, Horton, and Queen’s Cross, key members of each community joined the procession, making a statement about their local status within the community, and enthusiastically taking part in the theatre and physical display of politics. Outvoters in particular were incorporated into the civic body. Queen’s Cross was an easily recognisable landmark just outside of Northampton (a memorial built by Edward I on the death of his wife, Eleanor of Castile, in 1290), where most voters gathered to welcome the MPs into the town.

Just as processions were vital to kickstarting a campaign with a spectacle, so, too, were chairing processions, at the end of the election, meant to draw the eye and reunite the community. Squib books published after elections often preserved descriptions of the chairing route, incorporating the route into the collective memory of the town or city’s electoral geography. They show how carefully choreographed the event could be. When George Canning was elected in the Liverpool election of 1818, for example, the route and order of procession was published in advance (on 25 June 1818) to encourage ‘the Friends of Mr Canning’ to assemble and form the procession at 10 o’clock at the King’s Tavern the following day. It took two hours for the procession to be formed before Canning mounted his ‘triumphal car’ and the procession set off at a signal ‘given by a man… stationed on the summit of the Town-hall’.[5] The composition and order of the procession, and the elaborate accoutrements it required, were recorded in meticulous detail:

ENGLISH ENSIGN

Three Gentlemen on Horseback

Six Colours, three abreast

BAND

No. 1 Shipwrights

Six Colours, three abreast

[possibly No. 2 Rope-makers missing]

DRUMS and FIFES

No. 3 Sailmakers

Six Colours, three abreast

No. 4 Smiths

Six Colours, three abreast

DRUMS and FIFES

No. 5 Blockmakers

Six Colours, three abreast

No. 6 Riggers

Six Colours, three abreast

No. 7 Painters

Six Colours, three abreast

DRUMS and FIFES

No. 8 Coopers

Six Colours, three abreast

No. 9 Pilots

Six Colours, three abreast

No. 10 Bricklayers and Masons

Six Colours, three abreast

No. 11 Joiners and other Trades

Six Colours, three abreast

BAND

Gentlemen

Six Colours, three abreast

BAND

Mr Bolton

Committee

CHAIR

Six Colours, three abreast

Captain Commandant

Captains and Lieutenants follow in rotation, from No. 1 to No. 25

Spare Colours in the rear[6]

The procession started with men from Liverpool’s most prolific trades, largely dominated by those connected with the town’s character as a port city (shipwrights, sailmakers, riggers, and pilots). Each trade was followed by six ‘colours’ or flags decorated with symbols of their trade and in the colours of Canning’s campaign (red). Newspaper accounts recounted that, ‘The different artisans and mechanics, profusely decorated with red favours, were ranged under flags bearing symbols of their respective trades’, providing the tradespeople with a sense of pride and identity within the massive crowd. It also provided an opportunity for Canning to specifically thank these tradesmen for their support of his campaign by having them lead the procession.[7] The gentlemen who canvassed for Canning were also physically distinguished in the procession by their elevated position on horseback and wearing ‘on their hats the numbers of their districts in gold letters on a red leather ground… Red and blue flags, streamers, and ribbands, waved in rich profusion from almost every house’.[8] The streetscape of Liverpool was a sea of red favours, cockades, ribbons, streamers, and banners, creating a spectacle that dominated not only in terms of the size of the crowd, but also in bold colour.

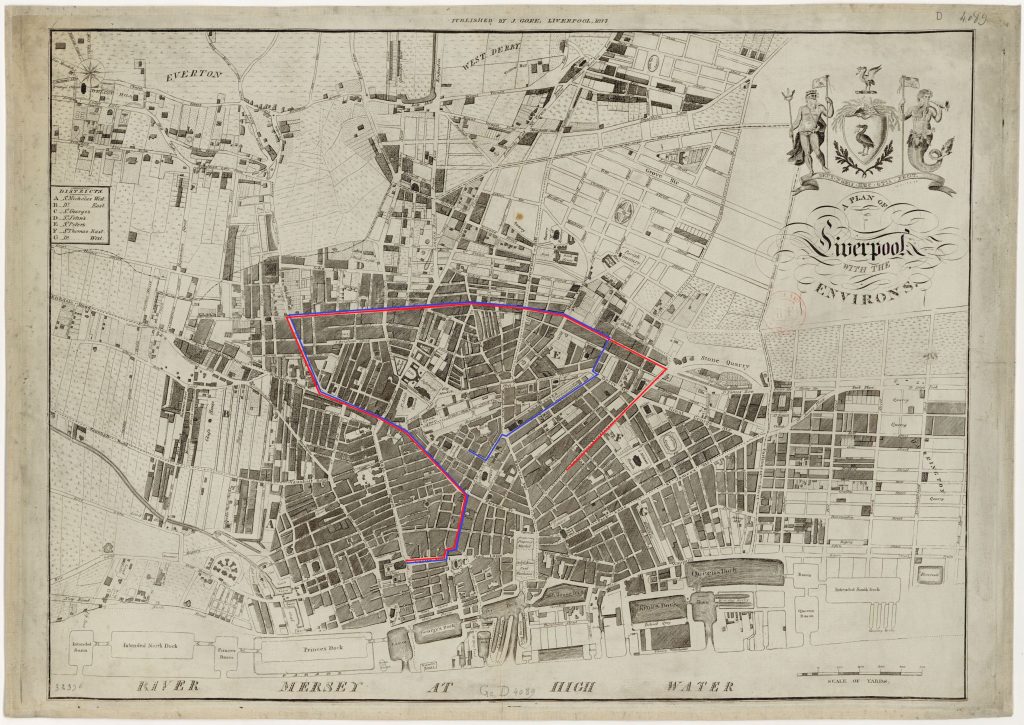

The route of Canning’s 1818 procession was different from that taken by his rival General Gascoyne, elected alongside him. The chairing route for Canning left the Town Hall, located quite close to Liverpool’s docks. The procession marched down Castle Street and up the main artery of Whitechapel, before traversing the edges of the city’s more densely built areas along St Anne’s Street to Rodney Street. The procession finally returned towards the centre of Liverpool, stopping on Duke Street where Mr Bolton lived.[9] Canning’s route passed through most of Liverpool’s districts (A-G on the map below). Just as the clothing of Canning’s canvassers acknlowledged Liverpool’s districts, so, too, did his victory procession route. Meanwhile, General Gascoyne’s procession diverged earlier, travelling down Bold Street and Church Street to the home of John Leigh (a gentleman) in Basnett Street. In both cases, the processions ended at the houses that the candidates had been staying in during the election and from the windows or balconies of which they had addressed the crowd.

A chairing procession provided an opportunity to thank key players in the campaign, including election agents, canvassers, and patrons, but also the voters themselves. However, the ritual of chairing did not only incorporate the voters, but the non-voters, too. At the Liverpool election, ‘Every window, balcony and even roof of the houses… was thronged with spectators’. When Canning’s procession concluded in Duke Street at the home of Mr Bolton, ‘what with the multitude already there, and the additional influx which it brought with it, the press became excessively and alarmingly great. Many females fainted; but, happily, so far as we have heard, no serious accident occurred to any person’.[10] While men participated in the procession itself, women and children were still active participants in the crowd within the larger cityscape. Canning alighted from his ‘triumphal car’ and entered 62 Duke Street, Mr Bolton’s home, before reappearing on the balcony to give a speech.

Not only did physical bodies dominate the streets, but the cityscape was also immersed in sound. At Liverpool, after every two or three groups of artisans and tradesmen were the flags, but also a group of fifes and drums. Drums would have regulated the pace of the procession, the sound carrying a long distance due to the bass sounds. The high-pitched sound of the fifes would have been heard, perhaps playing election songs. The fifers and drummers may have been hired from the army. Separate bands of musicians followed the tradesmen, providing a different aural cue to the crowd that the gentlemen canvassers were approaching. Another band also preceded Mr Bolton and Canning’s election committee, before the chair itself came into view. The effect would have been a cacophony of sound as layers of music and noise overlapped, a wall of perpetual sound, as one band followed the next as they passed the crowd. Processions were also visually arresting. The Liverpool chairs had been designed by Thomas Parr (a gentleman from Shrewsbury) and constructed by James Gill, an upholsterer in Virgil Street (both of whom split their votes between Canning and Gascoyne according to the poll book). Canning’s chair was ornate, and designed to be ‘read’ by observers:

The outside of the sides was formed by a festoon of flowers, supported by scrolls at each end, ornamented with rich rosets [sic]: underneath appeared the motto, ‘Ships, Colonies, and Commerce’, in silver, on a deep blue ribband. The back was circular: the upper part formed by a handsome frieze of blue silk, fluted and ornamented by wreaths in silver, the frieze edged with laurel; on the top of this was an ornamented tablet, with the number 1654 [signifying the number of votes received], supporting a chaplet of laurel: the lower part displayed rich draperies, depending from scrolls, which bore the arms of Great Britain and Ireland, and in the centre the Liverpool arms with gold enrichments. On the front were Mr Canning’s arms, with laurel, palm branches etc. In the inside, at the front part, was the Regent’s plume, on a crimson cushion, resting on an India chest, cornucopias &c. as emblems of commerce: the back part was covered with festoons of silk drapery, crimson and deep blue alternately, at the front of which stood an elegant chair, covered with crimson silk, and trimmed with gold lace, silver wreaths &c., elevated by circular steps; and on each side rose a scarlet flag, serving as occasional supporters: the royal standard waved over his head, with laurel entwined on the staff. The ground on the whole was scarlet cloth, silk, &c., trimmed with gold lace and fringe.[11]

General Gascoyne’s, on the other hand, was decorated as follows:

At the front appeared ‘King and Constitution’, in gold, and the crown, encompassed by laurel. The sides were formed by blue silk flags, the staffs placed in an angle and the silk neatly festooned, ornamented with silver wreaths &c. The back bore the Liverpool arms on fluted draperies, amidst festoons of silk and laurel: on the upper part was a rich ornament with the number 1444 [his total votes] in a wreath. In the inside was the chair, covered with light blue silk and trimmed with gold lace, placed on an elevation, bearing the crest of Liverpool: on each side were two fixed supporters, entwined with laurel, and carrying a festoon of flowers: on the back part of the car, and at the top was fixed scarlet draperies and the Regent’s plume encircled by laurel: on each side the royal standard and union waved as small flags.[12]

These costly chairs were decorated with flags, mottos, and symbols of victory and prosperity including laurel wreaths and cornucopias. The Indian chest also alludes to Canning’s position as President of the Board of Control (1816–1821) which was responsible for overseeing affairs in India and the East India Company.

The chairing for Henry Bright in Bristol in 1820 was another procession filled with pageantry. Not only can one get a sense of the festive atmosphere from newspaper reporting on the chairing, but also from a panoramic watercolour by attorney and amateur artist Henry Smith. The 24-plate image was painted for Henry Bright’s father, Richard, a prominent Bristolian banker and merchant. The procession was filled with flags and banners labelled with ‘Bright For Ever’ and ‘Bright and Loyalty’, with sailors carrying model ships on their shoulders. The 16-foot model ship Mars, can be seen firing its brass cannons in the streets. The route also celebrated Bristol’s Master-Porter, bakers, masons, upholsterers, as well as Westcott’s Brass Foundry, with men wear brass hats (specifically chapeau bras), and raising a brass tea kettle on a pole decorated with Bright’s ribbons.[13] Henry Bright was carried on a massive, red triumphal platform with his ‘chair’ adorned with gold, laurel, and tassels; and hoisted on the shoulders of 46 men with red and blue ribbons adorning their hats. The Bristol Mercury described it;

The Platform rested upon four Globes, which supported the Car, with Lions’ Feet, each foot resting upon a Rock, emblematic of the four parts of the United Kingdom and Great Britain and Ireland, and on each of which was tastefully displayed the Rose, the Thistle, the Shamrock, and the Leek, On the Platform, in front and rear, were four emblems in gold, of the Union of the Whigs of Bristol, surmounted by Doves, each bearing an olive-branch in his mouth. The whole Car was lined with crimson velvet, tufted with blue. The outside scarlet, decorated with heraldic bearings: on the sides the Arms of the Member, encompassed by wreaths of laurel; in front, in relief, the Royal Arms; on the back, the City Arms. The Chair was executed by Mr Hoskins, from a design by a Professional Gentleman of Mr Bright’s Committee. For taste and elegance it surpasses any thing of the kind we have ever seen.[14]

Bright’s procession was meant to make a statement about Bristol’s place within the United Kingdom, as an important port city for international trade and commerce. The Bristol Mercury reported that the procession through the streets of Bristol took over four hours from the High Street to the Bush Tavern, right next door to Mr Bright’s Committee Rooms. The electoral geography was engrained in Smith’s watercolour, as key buildings passed and streets used during the procession were inscribed on the bottom of the page to identify the landmarks.

At the end of the chairing, the candidates were usually taken back to their election headquarters where the chair would often be torn apart by the crowd. As a result, a surviving chairing chair is a rarity. However, at Hughenden Manor, a Gothic-style armchair (and one of two accompanying carrying poles) survives — only because it was not ever used for its intended purpose. It was made for the chairing of Benjamin Disraeli, had Disraeli been elected as an MP for Chipping Wycombe in the by-election of June 1832. The chair was painted in Disraeli’s campaign colours (cream and pink), and had metal brackets for two carrying poles to slot through to enable to the chair to be carried on the shoulders of multiple men to distribute and share the weight. In the event, Disraeli was not returned.

While many communities took pride in the order and regularity of chairing processions, there were instances when disgruntled voters and factions caused violence during the proceedings.[15] Following the 1807 Yorkshire election in York, where William Wilberforce and Lord Milton were returned, Lord Milton, ‘… mounted a very elegant chair, beautifully ornamented with laurel and orange coloured Ribbons, Silks, &c. – The procession proceeded three times round the Castle Yard, and paraded the principal streets of York’.[16] However, on approaching the George Inn, the headquarters of Milton’s opponent, Henry Lascelles,

… some wretch… threw a tile or a brick with excessive violence, which had very near struck Lord Milton’s head, and at the same moment, a vast number of ruffians, ‘who foolishly imagined that they could honour Mr Lascelles by disgracing themselves’, rushed out of their lurking places… and attempted to throw his Lordship from the Chair; in this attempt they fortunately did not succeed, but they did succeed in completely dismantling and stripping the chair of its ornaments…[17]

The attack on Lord Milton and his chair was an attempt to dismantle the visual identity of his campaign and disrupt the opportunity to bring the community together again. In Carmarthen in 1820, a mob rushed the Honourable John Frederick Campbell’s chair, and ‘forcibly took possession of the chair and demolished its decoration, then placed one of their own body in it, and carried him in triumph round the town’.[18] The chairing of Campbell was subverted, bodily overthrowing the elected MP from the chair and installing a disgruntled voter in the chair in his place.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, Georgian election rituals like chairing and processions began to dwindle. Liverpool’s last chairing ceremony was performed in 1831, although Dover’s lasted until 1852.[19] Frank O’Gorman argues that as more concrete political parties and identities were developed in the nineteenth century, the need for rituals that celebrated individual candidates over their parties did not hold the same relevance to the political landscape.[20]

[1] Coke and Birch. The paper war carried on at the Nottingham Election, 1803 (Nottingham, 1803), 307.

[2] Frank O’Gorman, ‘Campaign Rituals and Ceremonies: The Social Meaning of Elections in England 1780-1860’, Past & Present, 135 (1992), 83.

[3] Zoe Dyndor, ‘The political culture of elections in Northampton, 1768-1868’ (PhD thesis, University of Northampton, 2010), 182.

[4] MS Althorp F. 37, ff.155-6.

[5]Westmorland Gazette (4 July 1818), p.3 col.d-e.

[6] The squib-book, a collection of the addresses, songs, squibs, and other (Liverpool, 1818) 62.

[7] Westmorland Gazette (4 July 1818), p.3 col.d.

[8] Westmorland Gazette (4 July 1818), p.3 col.d.

[9] John Bolton was a Liverpool merchant who was heavily involved in the trade and ownership of enslaved peoples in the West Indies and South America.

[10] Westmorland Gazette (4 July 1818), p.3 col.d-e.

[11] Westmorland Gazette (4 July 1818), p.3 col.e.

[12] Westmorland Gazette (4 July 1818), p.3 col.d-e.

[13] Bristol Mercury (13 March 1820), p.3 col.a-b.

[14] Bristol Mercury (13 March 1820), p.3 col.b.

[15] Coke and Birch, 307.

[16] Yorkshire Election. A Collection of the Speeches, Addresses, and Squibs produced by all parties during the late contested election for the county of York (Leeds, 1807), 107-8.

[17] Yorkshire Election, 107-8.

[18] Bristol Mirror (18 March 1820), p.2 col.e.

[19] O’Gorman, ‘Campaign Rituals’, 114.

[20] O’Gorman, ‘Campaign Rituals’, 114-5.