A short introduction to poll books, and how they have survived

[5-minute read]

In their most fundamental manifestation, poll books are simply lists of voters’ names, recording the candidates for whom they polled. Prior to the introduction of the secret ballot in 1872, electors had to attend elections in person and verbally state their vote. From the late seventeenth century onwards, these votes were increasingly a matter of public record.

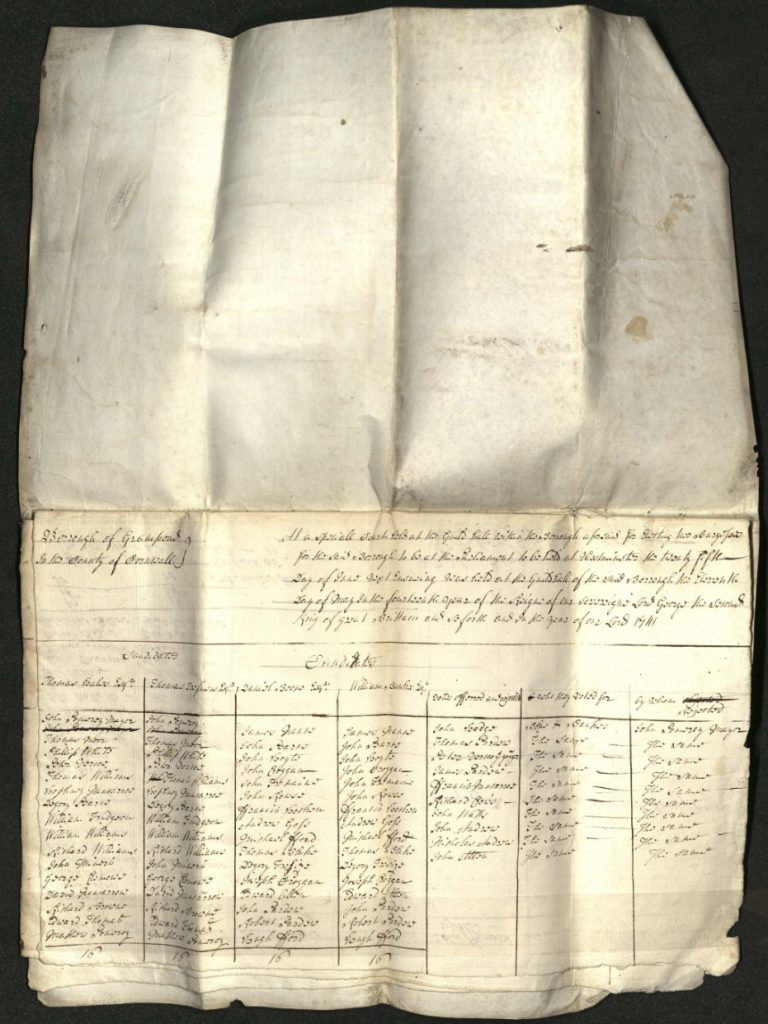

The practice of keeping poll books has obscure origins. It appears to have emerged in the early seventeenth century, primarily to provide evidence to the House of Commons of electoral misconduct (especially the admission of unqualified voters). From the 1690s onwards, the keeping of poll books became more regulated by Acts of Parliament. By 1711, a series of Acts of Parliament had decreed that Sheriffs must deposit poll books for county elections with the Clerk of the Peace within twenty days of the poll declaration, and that copies should be made available to anyone who wished to view it for ‘a reasonable charge’. It was not until 1843 that the permanent preservation of poll books was made mandatory for all constituency types. The creation of poll books during the period 1695–1832 was therefore sporadic. In any case, the number of surviving poll books was severely depleted in 1907 following the intentional destruction of the entire collection of poll books held by the Crown Office.[1]

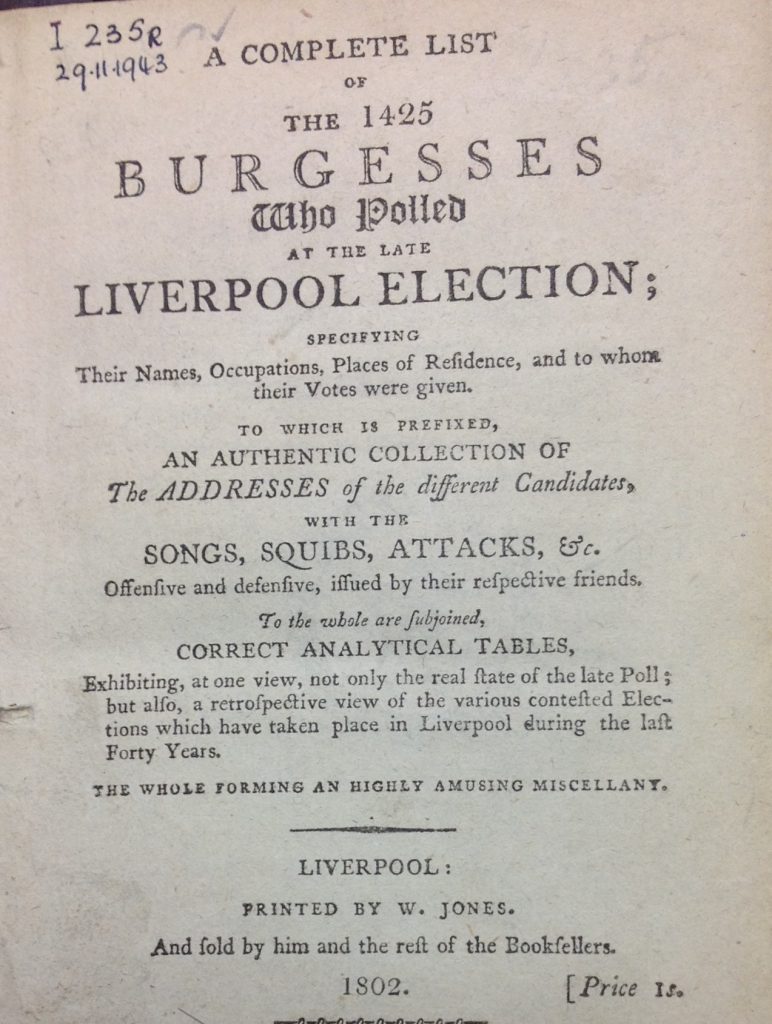

What survives today, then, falls within two broad categories: commercially printed poll books, and handwritten (or ‘manuscript’) polling results predominantly in local archives. The provenance of manuscript poll books can be obscure. Sometimes they are clearly the original sheets compiled by the official clerks at the time of voting (and held amongst the papers of solicitors, gentry families, or local government). Others are manuscript copies which were acquired by interested parties at a later point, and may have been re-arranged alphabetically or geographically by a scribe for ease of use.[2]

Those poll books that were printed were most commonly produced by local printers looking for profit. During the eighteenth century, it became increasingly common for rival printers within the larger urban boroughs to each publish their own edition of a poll book, suggesting the existence of a market for these works. The more self-important editors presented the publication of poll books as performing a vital public service. For example, the pro-reform compiler of the Cambridge University poll book of 1780 warned readers of the need to ‘guard as much as possible against corruption, patronage, and undue and secret influence in the electors and elected. To give some small check to this last seems to be a sufficient reason why all polls should be published’.[3]

Further Reading:

Baskerville, Stephen W., Adman, Peter and Beedham, Katharine F., ‘Manuscript Poll Books and English County Elections in the First Age of Party: A Reconsideration of their Provenance and Purpose’, Archives, 19 (1991), 384–403.

Cannon, John, ‘Short Guides to Records: Poll Books’, History, 47 (1962), 166–69.

Gibson, Jeremy, and Rogers, Colin, (eds.), Poll Books 1696–1872: A Directory to Holdings in Great Britain (Bury, 2008), 3.

Green, Edmund M., ‘New Discoveries of Poll Books’, Parliamentary History, 24 (2005), 332–67.

Green, Edmund M., Corfield, Penelope J., and Harvey, Charles, ‘Poll Books’, in Elections in Metropolitan London, 1700 – 1850: Volume I, Arguments and Evidence (Bristol, 2013).

Sims, John, (ed.), A Handlist of British Parliamentary Poll Books (Leicester, 1984), i–ii.

[1] John Sims (ed.), A Handlist of British Parliamentary Poll Books (Leicester, 1984), i; Jeremy Gibson and Colin Rogers, Poll Books 1696–1872: A Directory to Holdings in Great Britain (Bury, 2008), 3; Charles Harvey, Penelope Corfield, and Edmund M. Green, ‘Poll Books’, London Electoral History 1700–1850, 2–5.

[2] See Stephen W. Baskerville, Peter Adman, and Katharine F. Beedham, ‘Manuscript Poll Books and English County Elections in the First Age of Party: A Reconsideration of their Provenance and Purpose’, Archives, 19 (1991), 385–9.

[3] The poll for the election… (Cambridge: Francis Hodson, [1780]), iii–iv.