Gillian Williamson finds Black voters can be found by looking beyond the poll book [10-min read]

Historical Black voters have generally been found by knowing of the existence of a named, reasonably prosperous Black individual, preferably with some locational detail, and then searching for them in polling records. Most famously we have Charles Ignatius Sancho (1729?-1780), grocer, of Charles Street, St George Hanover Square, who voted in Westminster elections in 1774 and 1780. Sancho is usually described as the first, or even ‘only’, such voter.[i]

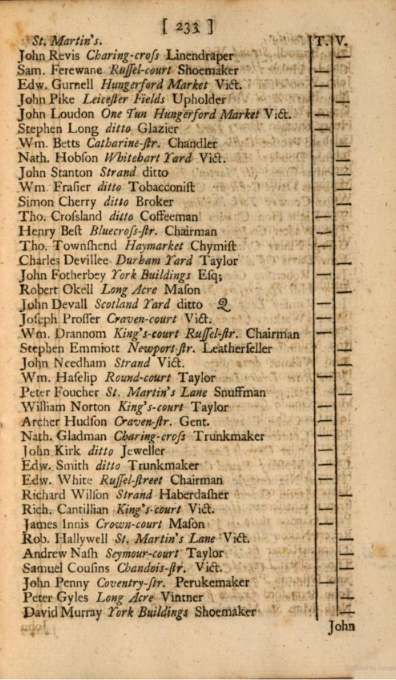

However, a recent archival finding has uncovered a Black Westminster voter a generation before Sancho, in the by-election of 1749. The ethnicity of this voter, whose name was John London, is revealed only because his vote was challenged. Had we only the published poll book entry – ‘John Loudon’ (a misspelling), One Tun [Alley], Hungerford Market, Vict. (victualler, the equivalent of a ‘pub landlord’) – his name would not have stood out in any way from close to 10,000 surrounding names.[ii] His entitlement derived from his standing as a British male, over twenty-one years old, who paid rates in his parish, in his case, St Martin-in-the-Fields.

The outcome of this by-election was a narrow win, a majority of 157 votes in a turnout of 9,465, for the government candidate, Lord Trentham (for whom London had voted). The losing candidate, Sir George Vandeput, petitioned for and was granted a scrutiny, a combative re-examination of the votes in which each side sought to have votes for the other struck out. Ahead of the scrutiny hearings Vandeput’s team prepared a printed pamphlet listing those they had ‘Reason to suspect not to be legal voters’. John London’s name is among them, this time correctly spelt but again with no racial identifier.[iii] It is in the manuscript record of the 1750 scrutiny hearings that this is revealed, although only incidentally. London’s vote was challenged on the grounds that he had not paid rates on his One Tun Alley premises. A witness, Mr Rybot, the St Martin’s overseer, had to admit that this was incorrect. Recently arrived in the alley, London was indeed not listed in the rates book for autumn 1749, but his name had been scribbled, alongside his payment, on the book’s blue cover. Rybot then added as a throw-away remark ‘…he’s a Blackamoor’. Next, London appeared in person and was questioned further about his background. To the enquiry ‘Where was [sic] you born?’, he replied ‘At St Edmundsbury [Bury St Edmunds] in Suffolk’. This satisfied the scrutiny, and his vote stood.[iv]

John London’s life is very thinly recorded elsewhere. No record of a baptism or early life in Bury St Edmunds has yet come to light. He was a ratepayer in One Tun Alley, a narrow passageway between the Strand and Hungerford Market, from September 1749 until September 1750. He then disappears from sight until admitted to the St Martin’s workhouse in March 1770, aged fifty and ill. On this occasion he was again recorded as Black. London died in the workhouse the following month and was buried in its graveyard.[v] The only other known record is in the Westminster register of licences. Under the previous licensee, Edward Creighton, the One Tun pub was known as The Three Compasses. In 1750 John Templeton took out a licence for The Ship.[MG1] John London named his business The Blackmoor’s Head.[vi] Although archival evidence for John London is scarce, what we have does tell us something important about a Black man voting in 1749. It is a timely reminder that concealed in the poll book data there may well be other Black voters who, unlike Sancho, are not otherwise known to us. Indeed, a Black man voting may not have been a particularly remarkable event. Despite a great deal of vituperative material in the press during the 1749 by-election, there is no mention of London’s presence at the hustings. London’s career as a publican, while brief and probably not especially successful, indicates that it was possible for a mid-century Black man to acquire a business and take premises that qualified him for a ratepayer franchise. In his small way London was, then, ‘independent’ and self-confident, as his pub sign perhaps indicates. Equally there are also indications that at times of vulnerability – when his right to vote was threatened and when he became a charge to the parish – his racial identity might be used against him. Blackness was not a bar to voting but perhaps it did suggest to white officialdom that an individual was not fully British.[vii]

[i] Vincent Carretta, ‘Sancho, (Charles) Ignatius (1729?–1780), author.’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 13 Jun. 2025. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-24609. (accessed 12.06.2025).

[ii] A Copy of the Poll for a Citizen for the City and Liberty of Westminster (London: J. Osborn, 1749), 233.

[iii] A list of the persons who, by the poll taken at the late election of a citizen to serve in Parliament for the city and liberty of Westminster, appear to have voted for the Right Hon. Lord Visc. Trentham, as entered in the Book opened for the Parish of St. Martin (Westminster: s.n., [1749]), title page, 4.

[iv] British Library: Lansdowne, 509 a and b, b, ff. 530d-531r; City of Westminster Archives Centre (‘CWAC’): F524, St Martin’s, rates book.

[v] CWAC: F4077, St Martin’s, alphabetical list of paupers admitted into the workhouse, 1769-77, f. 281; F419/234, St Martin’s, sexton’s daybook, 1767-71.

[vi] The London Archives: WR/LV/01/024, licensed victuallers register, 1743-52, St Martin’s, 1748, 1749, 1750.

[vii] For a fuller account of John London and the context of his life see Gillian Williamson, ‘John London, the Community Experience of a Black Man in Georgian London: Householder, Businessman, Voter’, Family & Community History 28.1 (2025), 30–51